Tag Archives: Brian Barnes artist

Secrets of the Viaducts: Walking the London Bridge to Greenwich Arches (Part Five)

* * *

After bridging the London Overground tracks, the arches of the London to Greenwich Railway cross Landmann Way; an isolated industrial road named after Thomas Landmann who first envisioned the pioneering viaduct in the 1830s.

The arches then approach the junction of Trundleys, Grinstead and Surrey Canal Road.

The Grand Surrey Canal

The route traced by Surrey Canal Road wasn’t originally a road at all- it was a waterway; part of the 2 ½ mile long Grand Surrey Canal which opened in 1810 for the purpose of transporting timber.

Linked to the Thames at Rotherhithe’s Greenland Dock, the canal’s route headed directly south, passing beneath the London and Greenwich railway arches before turning onto the stretch covered by the now tarmacked over Surrey Canal Road.

The waterway then headed along the present day Verney Road, passed underneath the Old Kent Road and then on through the area now occupied by Burgess Park before terminating at a basin between Albany Road and Addington Square in Camberwell.

The canal carried freight well into the 20th century but as the decades wore on, it began to receive increased competition from road transport.

Between the 1940s and 1970s, the canal was gradually closed down section by section, leaving a collection of muddy, rubbish-strewn troughs in its derelict wake.

The state of the canal near Wells Way (Burgess Park) as it appeared in 1960. (Image: The London Illustrated News).

In the 1980s the obsolete trench was filled in; its route transformed into paths and roads which have pretty much erased all trace of the former canal.

However, if you know where to look there are a few clues here and there as the following images illustrate:

Former canal bridge on Evelyn Street. The filled in area below is now occupied by industrial units. (Image: Google).

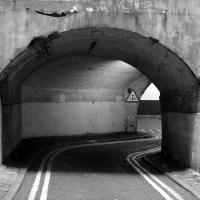

Canal Approach, off of Trundleys Road. The curved road here indicates the path once wound by the canal as it passed beneath the railway viaduct. On Canal Approach, it is still possible to spot the odd mooring ring buried in the dirt… (Image: Google).

Satellite view of the Canal’s old route through Burgess Park; now converted into a footpath (image: Google).

*

A Further V2 Catastrophe

After the Trundleys Road junction and close to where the canal once flowed, the London to Greenwich arches run past a small park called Folkestone Gardens.

The land now covered by Folkestone Gardens once bustled with streets and housing.

However, at 3.20am on the 7th March 1945 the site was struck by a V2 rocket, the huge explosion destroying much of the housing stock and killing 53 people.

Most of the fatalities were railway employees and their families, housed in flats owned by the Southern Railway.

The bombsite remained until 1970 when the rubble was cleared away and the peaceful green spot laid out.

*

Cold Blow Lane’s Cold War Politics

Shortly after passing beneath the viaduct, Trundleys Road becomes Sanford Street, off of which branches Cold Blow Lane.

On the corner of Sanford Street and Cold Blow Lane, you’ll spot a bold mural entitled Riders of the Apocalypse, painted on the end terrace of the Sanford Housing Co-op.

Created by Brian Barnes in 1983 when the cold war was decidedly chilly, the mural depicts Ronald Regan, Margaret Thatcher, Michael Heseltine (UK minister for defence at the time) and Soviet leader, Yuri Andropov, jockeying recklessly around the world on nuclear-tipped cruise missiles; a controversial weapon at the time due to its deployment on British soil at RAF/USAF bases Greenham Common and Molesworth.

The mural was a sequel to another of Brian Barnes’ south London murals… the terrifying Nuclear Dawn which was unveiled on Brixton’s Coldharbour Lane in 1981.

Nuclear Dawn; Brian Barnes’ other south London anti-war mural, pictured here in 1981 (Image: djfood.com).

Today, Nuclear Dawn can still be seen but is in a far sorrier state than its Deptford counterpart. There is currently a campaign to save it- please click here to learn more.

Deptford Station; Old Man of the Network

As we’ve seen in previous posts, in its first year the London and Greenwich Railway only ran a short distance between Spa Road and Deptford before being extended to London Bridge a year later; a quirk of history which granted Spa Road the accolade of being the capital’s first official railway terminal.

Spa Road has long since closed… but the Deptford stop is still very much in operation, essentially making it London’s oldest station to remain in service- and pretty much the world’s oldest working suburban station.

For many years, the station was from salubrious, characterized by dingy stairwells and small, cramped brick buildings.

However, in the past two years Deptford Station has undergone a drastic re-development, with a brand new forecourt introducing much needed doses of light and air.

*

The Deptford Project

On the high street, just over 100 yards south of the station, there sits The Deptford Project, based in the grounds of a former railway yard which was once annexed to Deptford Station.

The centrepiece of this refreshing community centre is a decommissioned 1960s train carriage which has been jazzed up and converted into a quirky café- I can safely vouch that the food and coffee served here is pretty marvellous!

The 35 tonne carriage has held pride of place on Deptford High Street since 2008 after being carefully towed by road from Essex at the achingly slow speed of two miles per hour.

When the carriage passed beneath the Deptford Station arch, there were just a nail-biting two inches to spare…

*

Rockin’ Out of Deptford

After departing Deptford Station, trains on the London to Greenwich arches brush past the Crossfield Housing Estate which, despite appearing pretty run of the mill, actually boasts some surprising links with the history of British pop-music….

In the late 1970s, one of the estate’s blocks- Farrer House, which sits right beside the viaduct on a road known as Creekside, was deemed by the local council to be unsuitable for housing those with families.

Consequently, the accommodation was offered to young, single tenants; many of whom happened to be struggling artists and musicians.

Amongst these down-at-heel residents were a number of performers from Deptford based band Squeeze (for whom Jools Holland was famously the original keyboard player).

Very much a quintessentially London band, Squeeze went on to have success in both the UK and the USA with songs such as Cool for Cats, Tempted and the bittersweet classic, Up the Junction which can be heard below:

Around the same time, Farrer House was also occupied by the fledgling band, Dire Straits.

In 1977, the Crossfield Estate provided the unlikely setting for Dire Straits’ first ever gig.

With the Deptford Music Festival in full swing outside, the band decided to plug their instruments into the flat’s electrics, trail the wires outside and preform an impromptu set on the lawn.

Dire Straits playing their first gig right beside the London to Greenwich arches, 1977. (Image: News Shopper).

Like Squeeze, Dire Straits were a regular act on Deptford’s club and pub scene, playing in venues such as The Duke and The Bird’s Nest before hitting the bit time.

The atmosphere of this south London pub scene was evoked in Dire Straits’ 1978 hit, The Sultans of Swing (please click below to listen):

In 2009 a plaque was unveiled on Farrer House by the Performing Rights Society to commemorate Dire Straits’ earliest gig.

The band is also linked to mural entitled Love Over Gold (the title of a Dire Straits album and single) which was painted outside Farrer House in 1989.

Commissioned by the Inner London Education Authority and Dire Straits themselves, the mural was painted by local youngsters in support of Outset UK; a now sadly defunct charity which had been established to help disabled people.

Today, Farrer House maintains its artistic links thanks to the Cockpit Centre, to which it is now home.

*

Dancing in Deptford

Creekside is also home to the Laban Dance Centre; a major college of dance and arts named after its founder, Rudolf Laban.

Born in Austria-Hungary in 1879, Rudolf Laban opened a number of schools across Europe, pushing dance towards the level of accepted art form.

Following the rise of Nazism, Laban fled to Britain in 1938 and, ten years later, opened a dance school in Manchester; the genesis of the centre which now stands in Deptford.

Designed for a competition in 1997 and unveiled in 2002, the current Laban Centre on Creekside is the world’s largest purpose built dance school and one of London’s most intriguing examples of contemporary architecture.

It was designed by Swiss architects, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron- the team who also masterminded the conversion of the Tate Modern and the design of Beijing’s 2008 Olympic stadium.

*

History in the Making

Creekside itself takes its name from Deptford Creek; the point at which the 11 mile long Ravensbourne River enters the Thames.

As it approaches Greenwich, the railway viaduct crosses this body of water.

It was at Deptford Creek in 1580 that The Golden Hind finally came to rest after its monumental circumnavigation of the globe. Shortly after its arrival, Queen Elizabeth I boarded the ship to bestow a knighthood upon the captain, Francis Drake.

*

And now the end is near…

After crossing the Thames tributary the three and a half mile long viaduct finally begins its descent into Greenwich; our final destination on this tour.

The arches reached Greenwich in December 1836 and the handsome station building, designed by architect George Smith, dates from 1840.

As well as helping commuters travel back and forth between the city, Greenwich station was also instrumental in encouraging poorer Londoners to take daytrips away from the squalor of the city centre.

Today, the pleasant district remains a popular destination, noted for its seaside like atmosphere.

Back in the ticket hall of the station, a small plaque hangs quietly on the wall, commemorating the railway’s place in the capital’s history.