My next book….

I’m very pleased to announce that I recently secured a deal with the Crowood Press for my second book: a history of Waterloo station.

Waterloo station in the 1960s by Terence Cuneo

Due to the amount of writing and research this project will require, it is likely that my posts here will become less frequent over the next few months.

But please, fear not; I have not forgotten this site!

In the meantime, please click below to view a short, quirky film called ‘Rush Hour‘ which was made at Waterloo station in 1970:

*

Droogs About Town: London Locations Featured in ‘A Clockwork Orange’

Released in 1971 and directed by Stanley Kubrick, A Clockwork Orange was by far one of the 20th century’s most controversial films.

Poster for A Clockwork Orange

Based on Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel of the same name (the title being inspired by the old Cockney phrase “as queer as a clockwork orange’), the story is set in a dystopian London of the near future and centres on Alex DeLarge–a sadistic youth with a passion for Beethoven- who leads his gang of ‘droogs’ through the city on nightly sprees of ultra-violent mischief.

Alex De Large stares at the camera in the film’s iconic opening shot…

After committing murder, Alex is finally locked up… but is soon offered a quick way out when he agrees to act as a guinea pig for the Ludovico Technique; a controversial brain-washing programme designed to suppresses the desire for violence (and something which caused actor Malcolm McDowell great pain and discomfort when it came to portraying these disturbing scenes).

Alex undergoing the Ludovico Technique

In Britain, thanks to high levels of upset whipped up in the press, the film version of A Clockwork Orange gained such an intense notoriety that Stanley Kubrick himself withdrew his work from circulation; a self-imposed ban which remained right up until 2000.

So strict was this embargo that, in 1993 when the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross attempted to screen the film, Warner Brothers took the owners to court; an action which led to the cinema going bust thanks to the immense legal costs involved.

Considering A Clockwork Orange was filmed entirely around London and the Home Counties (including areas such as Borehamwood, Kingston-Upon-Thames, Elstree, Radlett, Brunel University, Bricket Wood and Wandsworth prison) it’s rather ironic that British audiences were forbidden from viewing Kubrick’s film for so many years.

Here are some of the film’s most prominent London-based scenes:

The Chelsea Drugstore

Whilst Alex’s nights are spent committing all manner of horrific acts whilst tanked up on drug-laced milk, his days are rather more civil… devoted to indulging his love of classical music; especially that of the “lovely, lovely Ludwig Van” Beethoven.

In one of the film’s scenes, we follow Alex, decked out in his dandiest threads as he peruses his favourite record shop (click below to view):

This scene was filmed in the basement of the Chelsea Drugstore; a modern building fashioned from glass and aluminium which opened on the King’s Road in 1968.

Open 16 hours a day, 7 days a week, the Chelsea Drugstore was an avant-garde, mini shopping mall, its three floors boasting eateries, boutiques, a record shop, bar, newsagent and chemist.

It also boasted its own ‘Flying Squad’… an exclusive team of women clad in purple castsuits who were employed to make unconventional home deliveries on their fleet of motorbikes. Groovy!

The Chelsea Drugstore was also name checked in The Rolling Stone’s 1968 hit, You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” (Speaking of The Stones, Mick Jagger was once earmarked to play Alex DeLarge in an earlier proposed adaptation of Burgess’ novel which never came to fruition…)

Although the Chelsea Drugstore ceased trading in 1971, the shops in the basement (as featured in A Clockwork Orange) remained in place until the late 1980s whilst the rest of the building became a wine bar.

Today, the building is occupied by the Chelsea branch of McDonalds.

*

Thamesmead

Despite the inclusion of the psychedelic Chelsea Drugstore, A Clockwork Orange is mostly set against a cold, dystopian backdrop; a precedent set in Burgess’ original novel as the following excerpt, in which Alex and his gang are evading the police, atmospherically illustrates:

“Just round the next turning was an alley, dark and empty at both ends, and we rested there, panting fast then slower, then breathing like normal. It was like resting between the feet of two terrific and very enormous mountains, these being flatblocks, and in the windows of all the flats you could viddy like blue dancing light. This would be the telly. Tonight was what they called a worldcast, meaning that the same programme was being viddied by everyone in the world that wanted to… and it was all being bounced off the special telly satellites in outer space.”

In order to realise Burgess’ bleak, futuristic vision Stanley Kubrick turned to the modern, Brutalist architecture which was sprouting across London during the era in which the book and film were created; architecture which, as early as 1962, Anthony Burgess was already predicting would provide fertile ground for many unforeseen social ills.

In Burgess’ novel, Alex lives in “Municipal Flatblock 18a”, a block daubed in obscene graffiti and plagued by vandalism.

To represent this domestic seediness, Kubrick took his film crew to the newly built Thamesmead Estate; a vast, sprawling development near Woolwich in South East London.

Built on a former military site, the Thamesmead Estate, which was optimistically promoted as being the “town of the twenty-first century”, was built piecemeal between the 1960s and 1980s.

One of the film’s most famous sequences takes place on Thamesmead’s Binsey Walk.

Walking alongside the man-made Southmere Lake Alex, whose leadership has just been challenged, decides to show his droogs whose really in charge (click below to view):

In recent years, the Thamesmead Estate has been used as a set for the E4 comedy, ‘Misfits‘.

*

York Road Roundabout, Wandsworth

One of the most notorious scenes in Kubrick’s adaptation takes place at the very beginning of the film and involves a vicious assault on a hapless down and out as he lies drunkenly in a grimy, pedestrian subway.

The scene was filmed in the warren of walkways beneath York Road roundabout, which sits at the southern foot of Wandsworth Bridge.

Typical of the architecture of the time, York Road roundabout was laid out in 1969 and was pretty much brand new when Stanley Kubrick set up his cameras.

Stanley Kubrick with Malcolm McDowell on set below York Road roundabout, 1971 (image: Stanley Kubrick Archive).

Today, the labyrinth beneath the roundabout is just as bleak and unwelcoming as it was some 40 years ago…

More recently, a large atom-esque sculpture of sorts has been plonked down on the roundabout, becoming something of a local landmark.

Apparently inspired by the 1950’s Atomium sculpture in Brussels, but kitted out with a bulky and intrusive advertising gantry, the tangle of metal doesn’t really do much to beautify the 1960s concrete…

*

Albert Bridge

As for the unfortunate tramp who was attacked by Alex and his droogs below Wandsworth’s grimy roundabout… don’t worry, he gets his own back…

After recognising the recently released (and now, thanks to his treatment, defenceless) Alex DeLarge glumly contemplating a view of the Thames, the tramp leads his own rabble in a revenge attack on the former and now defenceless yob, right beneath Albert Bridge; one of London’s most beautiful river crossings (click below to view):

*

Want more on Stanley Kubrick’s London? Then check out this post: A Monolith in St Katherine Docks…

***

A History of the Elephant & Castle (Part Two)

This is the second part looking at a history of the Elephant and Castle area of south London. To read the first instalment please click here

The Elephant at war

Being a major transport hub with a large civilian population, the Elephant and Castle was bombed heavily during World War Two.

The worst raid to hit the area took place on the 10th May 1941, when bombers deliberately targeted the south London district in order to create a ferocious firestorm which rapidly engulfed the Elephant.

After the war much of the Elephant lay in ruins, a shadow of its pre-war days when Londoners had flocked there to indulge in its many shops and places of entertainment.

A concrete renaissance

For over a decade, the Elephant remained pretty much in tatters, pitted by numerous bomb craters which provided exciting playgrounds for local kids.

In March 1958, the down-at-heel area received a welcome dash of American glamour when rock and roll star, Buddy Holly played to a huge audience at the Elephant and Castle’s Trocadero.

Buddy Holly, backstage at the Elephant & Castle Trocadero, March 1958. (Image by Bill Francis, from Patrick Sweeney website)

To read more about Buddy Holly’s time in London, please click here.

*

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, town planners were hard at work, drawing up plans for a massive redevelopment of the area… for Elephant and Castle was about to become a huge canvas for some of London’s most prominent post-war architecture.

The importance of the vast rebuild was summed up in 1956, when the London County Council stated:

“The Council regards the Elephant and Castle as one of its most important comprehensive reconstruction projects. A unique opportunity is presented for creating a new shopping, business and recreational centre for south London, for effecting major traffic improvement and for realising fine, civic design.”

The new road-layout was the first part of the scheme to be implemented, with two huge roundabouts stamped down during the 1950s.

This prominent road system was highly representative of the mood of planners at the time, who envisioned a future in which the motor car would be king.

Consequently, little thought was given to those who had to traverse the Elephant on foot and, to this day, pedestrians are forced to cross the area via a series of gloomy, narrow subways.

It was during the 1960s that the majority of the Elephant was rebuilt; the architects’ love affair with concrete and stark urban planning resulting in the heart of the district evolving into a landscape more akin to communist East Berlin…

The very first building to be completed at the new Elephant was the Faraday Memorial; an avant-garde electricity sub-station, clad in stainless steel and plonked in the middle of the northern roundabout.

Unveiled in 1961 as a taste of things to come, the Faraday Memorial can still be seen in its original location, un-disturbed by the many millions of vehicles which have roared around it during the past fifty years.

Next to pop up was Alexander Fleming House which opened in 1963.

Alexander Fleming House. Now known as ‘Metro Central Heights’, the exterior of this 1960s development has since been fitted with blue and white cladding. (Image- Design Museum)

Originally designed as a triple set of office blocks, Alexander Fleming House has since been converted into luxury apartments and renamed Metro Central Heights (or, as some like to jokingly call it, Metro Sexual Heights; a reference to the many young, urban professionals who now reside there!)

The modern trio of towers was designed by Erno Goldfinger, the infamous architect noted for his bold, uncompromising buildings… and egotistically fierce temper!

To find out more about the curmudgeonly Goldfinger, please click here for my earlier post on the ‘Trellick Tower’ which is widely regarded as his true masterpiece.

*

Lost cinemas

Goldfinger would go onto wield great influence over the Elephant and Castle.

In 1966, he incorporated an Odeon cinema into Alexander Fleming House… which was rather fitting considering the complex was built on the site of the former Trocadero which had been demolished a few years after Buddy Holly’s celebrated visit.

Designed in the Brutalist style, the modern Odeon contained seats for over 1,000 movie-goers.

Sadly, the cinema was demolished in 1988 which is a real shame as, given current trends, I have a feeling it would have found a new lease of life as an independent picture-house had it been allowed to remain.

The Odeon at Elephant and Castle in 1983- by which point it had been renamed the ‘Coronet’ (many thanks to flickr user dusashenka for this rare image)

*

Tickled pink

In 1965, yet another Goldfinger creation was unveiled in the area… the Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre.

At the time, this new building was revolutionary; the first covered shopping complex in Europe.

Locals however who, for generations had patronized traditional local shops and markets, were slow to embrace the new concept.

When the shopping centre first opened, trade was painfully slow with just 29 out of 120 shop units being occupied.

Originally providing three floors for trade, it quickly became clear that this was one floor too many.

In 1978 the centre was purchased by Ravenseft Properties who promptly converted the third level into office space. As a spokesman for the company said at the time, “one has to do something when one has inherited such a horrible asset!”

In 1990, the powers that be thought it would be a good idea to paint the Elephant and Castle shopping centre bright pink, a colour which remained on the building until very recently.

I’ve often wondered what the idea behind this lurid scheme was. Not that I have anything against pink, but I was under the impression that a ‘pink elephant’ was something one only saw after a few to many sherries!

Some rather creepy pink elephants can be seen in the following excerpt from the 1941 Walt Disney classic, Dumbo, in which the lovable little elephant hits the booze rather too hard…

The Heygate Estate

By far the largest post-war project to grace the Elephant and Castle was the vast Heygate Estate, which was completed in 1974 and provided homes for 3,000 people.

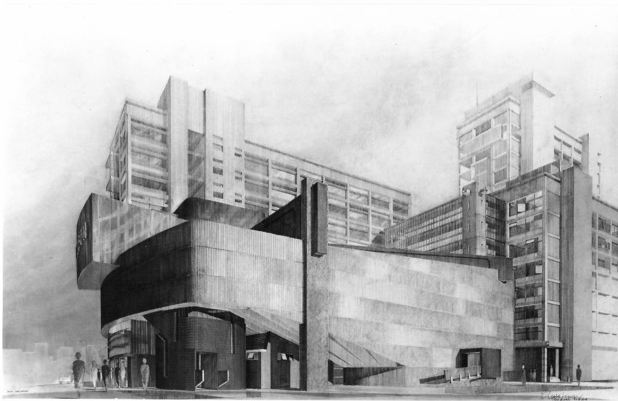

Designed by Tim Tinker, the Heygate Estate was very much a product of its time; a huge housing scheme conjured on an incredibly ambitious scale, and designed with the best of intentions in mind.

Aiming to make the estate an oasis of calm away from Elephant’s characteristic roar of traffic, Tim Tinker placed the tallest of the tower blocks around the perimeter, encircling and shielding smaller accommodation and areas of greenery within the middle.

When viewed from above, it is indeed surprising just how much greenery the Heygate encompassed.

However, as with many estates, the utopian ideal quickly became sour, with the modern innovations having quite the opposite effect of their intended purpose.

The towering apartment slabs isolated their inhabitants, slicing off communities rather than drawing them together, whilst the windswept walkways and secluded communal areas provided fertile breeding ground for crime and anti-social behaviour.

Unfortunately, unlike other examples of London Brutalist architecture- such as the Trellick Tower, National Theatre and Barbican Centre- the Heygate has received no revival and is currently undergoing demolition.

Thanks to the large amounts of asbestos present, the destruction is a slow process, not expected to be completed until 2015.

At present, the drawn out wrecking of the Heygate has made the old estate quite an atmospheric place; a vast, inner-city chunk of quiet decay, rather like something out of a post-apocalyptic film.

Despite being eerily deserted, at the time of writing, a tiny handful of residents are refusing to leave their homes on the Heygate in protest at Southwark council’s compulsory purchase order.

This small but hardy bunch include an elderly couple with a leasehold… both of whom are in their 80s and, like their small band of remaining neighbours, see the Heygate as their rightful home…

*

The Elephant on Film

Thanks to its present state, the Heygate has proved a popular location for movie makers in recent years, with Southwark Council raking in a substantial £91,000 in filming fees since 2010.

Two films to make substantial use of the estate are Harry Brown and Attack the Block.

Released in 2009, Harry Brown stars Sir Michael Caine who, just like Sir Charles Chaplin a generation before, spent his tough working-class childhood in the Elephant and Castle area.

In Harry Brown, the popular actor plays a pensioner after whom the film is named; an ex-soldier living out his twilight years on a hellish council estate.

One night, Harry has to rush to hospital, where his wife is dying.

Despite the emergency, he is too terrified to take a short-cut as the subway in question is plagued by gangs and drug-fuelled violence. His failure to take the shorter route means that he is unable to be at his beloved wife’s bedside when she passes away…

This, coupled with the murder of his friend who also resided on the estate, leads the pensioner to turn vigilante…a very grim film indeed.

*

Being a comedy, Attack the Block is one of the more cheery films to emerge from the Heygate Estate.

Released in 2011, this movie centres on a gang of youths… who find themselves having to defend their turf against an alien invasion!

As can be seen in the following trailer, the Heygate Estate played an integral part in the story:

More recently, the Heygate has been used as a backdrop for World War Z; a horror film in which the world is gradually taken over by zombies.

Due for release in 2013, the film stars Brad Pitt, who spent time on the estate filming some rather terrifying looking night scenes…

*

The Heygate is not the only the only area of the Elephant and Castle which has been used as a filming location.

In the 2011 film, The King’s Speech, Iliffe Street, just south of the junction towards Kennington, was used to represent a road in fashionable West London.

In 1968, the then brand new shopping centre featured in The Strange Affair which starred Michael York.

In 1987’s gangster film, Empire State, the young protagonist and his moll live in Draper House, their balcony overlooking the Elephant’s large twin roundabouts.

In 1982, the Elephant loaned its streets to the music industry when Brook Drive– which lies just west of the junction behind the Metropolitan Tabernacle, was used to film the video to the much-loved hit, Come on Eileen by Dexy’s Midnight Runners.

Please click below to view:

In the past year, I have had two fares to Brook Drive and, in both cases, each of the passengers stated how chuffed they were to live on the same street where this hit, which seems to be played at every single wedding reception, found a home for its video!

Below is a photo of the Brook Drive newsagent as it appears today:

Also in 1982, Dexys Midnight Runners released The Celtic Soul Brothers which was filmed on the other side of the Thames at the Crown Pub in Cricklewood- please click here to read more).

*

All change at the Elephant

Today, the Elephant and Castle is undergoing its biggest change since WWII.

A smashed up information board outside the Elephant shopping centre. Hopefully, such ugly scenes will soon be a thing of the past…

As part of a £1.5 billion scheme, the 1960s shopping centre is due to be demolished and replaced with a pedestrianized market square and green open spaces.

As for the Heygate Estate, once that has been fully knocked down, the empty land will be replaced with 2,500 new homes, of which it is sad 25% will be “affordable”… I suppose that means the other 75% will be unaffordable then…

Overall, the change at the Elephant is estimated to take some 15 years.

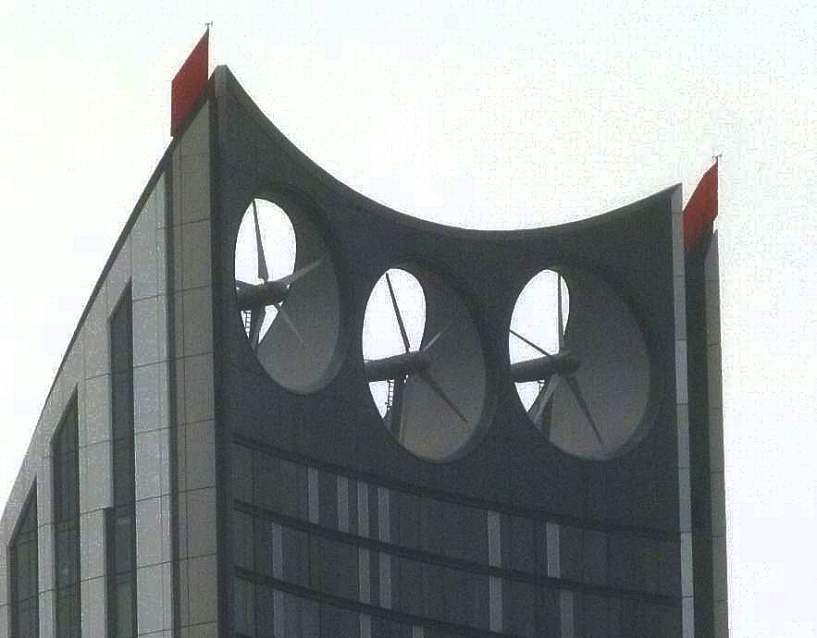

At present, the most prominent sign of this slow evolution is the Strata Building; a new tower which replaced Castle House and has been nicknamed by some Londoners as the ‘Lipstick’ building.

The Strata contains 310 luxury housing units, retail space at ground level and, most famously, three wind-turbines on its roof which are used for powering a small percentage of the tower’s utilities.

Wether of not these new developments will last longer than their 1960s predecessors remains to be seen… however, one thing is for sure- they are merely the next stage in the long and varied history of the Elephant and Castle.

***