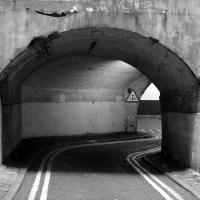

Lower Robert Street… a Ghostly Tunnel in the Heart of London

Mere moments away from the very centre of London there lies a quiet, almost secret little road called Lower Robert Street.

Entrance to Lower Robert Street…

Sandwiched between the Strand and Victoria Embankment and running through a twisting tunnel, Lower Robert Street is a covert cut-through we cabbies sometimes like to use if in the area and wishing to make a quick exit down to Victoria Embankment.

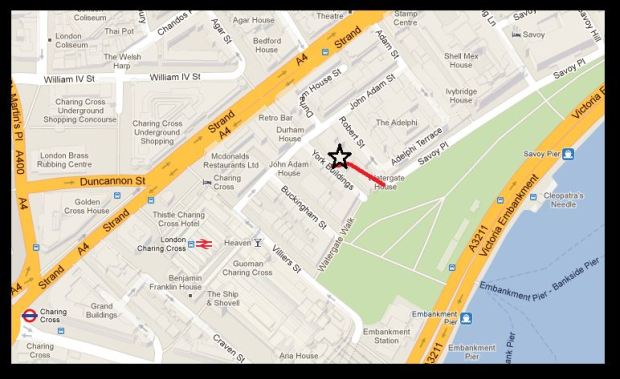

Map showing the location and approximate path (marked in red) of Lower Robert Street

Apart from the echo of the odd Taxi or bike courier, the archaic lane is pretty much devoid of any other traffic or people…

In recent years, Lower Robert Street’s grotto like appearance has gained it a nickname: the ‘Bat Cave‘!

Going underground… the modern extension of Lower Robert Street

Lower Robert Street dates back to the late 18th century, created as a by-product of ‘The Adelphi’; a large housing development consisting of 24 grand, terraced houses.

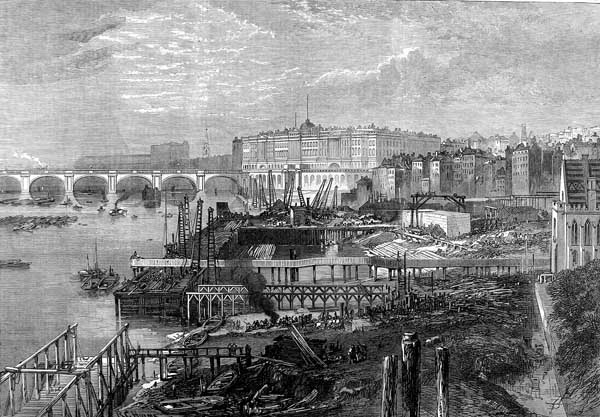

The Adelphi

The project was developed by four Scottish brothers; John, Robert, James and William Adam, whose fraternal bond blessed the scheme with its name- ‘Adelphi’ being the Greek word for brothers.

Construction began in 1772, with many of the labourers who worked on the project also being Scottish.

Nowadays of course you’ll often hear battered radios crackling away on building sites, but when the Adelphi was being built, music for the toiling workers was provided by a group of specially employed bagpipers!

The Adelphi in later life, shortly before its demolition in the 1930s

Because it was so close to the river Thames, the Adelphi was located on a slope.

The main building – the row of ornate houses- remained level with the Strand, jutting out over the incline.

To fill in the large void below, a complex of vaulted arches and subterranean streets were created- of which Lower Robert Street is now the only remaining example in practical, public use.

Vintage photo of the entrance to Lower Robert Street (image: British History website)

One other vault does exist it can be found in the rather more protected environment of the Royal Society of Arts on nearby Durham House Street:

Remaining Adelphi arches incorporated within the Royal Society (image: Royal Society)

Many famous people lived in the grand apartments above including the actor David Garrick, Richard D’Oyly Carte (founder of the nearby Savoy hotel), Charles Booth (the great, Victorian social reformer) and a number of notable literary figures including George Bernard Shaw, Sir J.M Barrie and Thomas Hardy.

The Adelphi- and in particular the subterranean lair which lurked beneath- was also mentioned in Charles Dickens’ 1850 masterpiece, David Copperfield;

“I was fond of wandering about the Adelphi, because it was a mysterious place, with those dark arches. I see myself emerging one evening from some of these arches, on a little public-house close to the river, with an open space before it, where some coal-heavers were dancing; to look at whom I sat down upon a bench. I wonder what they thought of me!”

*

In the late 1860s much of the Thames in central London was reclaimed as part of a vast engineering program to improve the city’s sanitation, the waters pushed back as the wide Victoria Embankment was built.

Victoria Embankment under construction, 1865 (image: Wikipedia)

This major road (which to do this day still conceals a vital sewer) was built right in front of the Adelphi’s lower vaults and roads, robbing them of their tranquil riverside location.

Once cut off from the Thames, the area beneath the Adelphi sank into decline, rapidly becoming a gloomy, foreboding place.

In line with much of Victorian London, the twisting underground roads became a haven for beggars and criminals. As one historian noted; “the most abandoned characters have often passed the night” beneath the Adelphi, “nestling upon foul straw.”

A famous image depicting the appalling conditions in which London’s Victorian poor existed. Such a sad sight would have been common place beneath the Adelphi.

Unsettlingly (and, perhaps unsurprisingly), Lower Robert Street, which was once an ingrained part of this depressing area, has its own resident ghost….

The phantom is known as ‘Poor Jenny’; a prostitute who lived and worked in the depths of Lower Robert Street, the bed upon which she languished being no more than a grotty pile of rags.

Deep within Lower Robert Street…. the haunt of ‘Poor Jenny’…

It is said that late one night, Jenny was throttled by one of her clients… today, her screams and gasps can be heard echoing through Lower Robert Street, the awful noise accompanied by a rhythmic tapping; the sound of Jenny kicking the floor as she fights against the strangulation…

Perhaps that’s why the powers that be choose to close the road every night between midnight and 7am…

The Cruel Capital: Two Grim Road Firsts

When not respected or used in the correct manner, roads can be very dangerous places indeed.

Driving for a career as I do, I’ve seen my fair share of road accidents; some trivial, others shockingly nasty.

In the first decade of the 21st century alone, 32,955 pedestrians, cyclists, bikers and vehicle occupants were killed on Britain’s roads, with another 3 million injured.

According to the charity, Road Peace, it is estimated that, worldwide, 4,000 people are killed on the road every single day.

Sobering figures indeed.

*

It was in 1926 that the British government first began to collate statistics on road deaths.

However, fatalities were taking place long before that, with London’s suburbs witnessing two grim firsts in the closing years of the 19th century.

The first ever fatality involving a car striking a pedestrian occurred at Crystal Palace, South London on 17th August 1896.

The unfortunate victim was 44-year-old, Mrs Bridget Driscoll from Croydon.

Bridget Driscoll (circled)

At the time of the accident, Bridget was making her way to a display of folk-dancing which was being held in Crystal Palace Park.

Stepping out onto a now vanished road called Dolphin Terrace, the unfortunate pedestrian was startled to see a car coming towards her…

Estimated location of ‘Dolphin Terrace’, marked out in red

It must be remembered that in 1896, cars were a true novelty.

This particular car- a Roger Benz which belonged to the Anglo-French Motor Car Company was out on the road giving demonstration rides to excited passengers, keen to have a go on the new technology.

A Roger Benz

Upon seeing the pedestrian, the car’s driver, Arthur Edsel rung a bell, shouted a warning and swerved the vehicle… but it was to no avail. The bewildered Bridget was struck and she died at the scene minutes later from a head injury.

At the time of the impact, the car was travelling at 4mph… a speed which one witness described as a “tremendous pace… as fast as a good horse can gallop.”

Despite this Victorian recklessness, it was decided that Bridget’s death was accidental, the coroner stating that he hoped “such a thing would never happen again”…

*

A few years later in 1899, another unfortunate first for Britain’s road network occurred, this time at Harrow in North-West London.

This incident involved one Major James Richer and a Mr Edwin Sewell.

After a distinguished military career including service in India, Major Richer had returned to London where he landed a high-ranking job with the Army and Navy department store on Westminster’s Victoria Street (today rebuilt as a branch of House of Fraser).

The Army & Navy Store, Victoria Street 1895 (photo copyright City of London)

On the look out to expand the department store’s ever increasing range of diverse goods, Major Richer thought it would be a good idea for the large shop to start shifting cars.

With this in mind, he turned to the Daimler motor car company who were only too happy to oblige, arranging a test drive for the 25th February 1899. The chap behind the wheel would be Mr Edwin Sewell.

*

On the day of the demonstration, the party clambered into the 8 seater vehicle and trundled all the way up to Harrow-on-the-Hill; a picturesque location which is still home to the famously exclusive school and offers a wonderful panoramic view over the capital.

An 8-Seater Daimler from the 1890s (photo: National Library of Ireland)

Once upon the hill, the group stopped for a meal at the King’s Head Hotel… no doubt including some liquid refreshment!

The King’s Head, Harrow-on-the-Hill (from Old UK Photos)

After their break, Edwin Sewell once again took to the wheel, heading north along Harrow-on-the-Hill’s high street, passing the many, cluttered buildings of the prestigious Harrow School.

As they approached the junction of Grove Hill and Peterborough Road where the path begins to slope downwards, disaster struck…

Gathering speed, the vintage vehicle’s speedometer began to notch up towards a hair-raising 14 mph, forcing Edwin to slam the brakes. This sudden action resulted in the collapse of a rear wheel, causing the Daimler to tip over.

Site of the UK’s first accident involving the deaths of the vehicle’s occupants

Google map showing the location of the fatal Harrow accident

Edwin Sewell was thrown from his mechanical charge and died instantly.

Major Richer was less lucky and ended up pinned beneath the hefty vehicle. He was rescued but died from his injuries a few days later on the 1st March.

This incident thus made the pair the UK’s first ever car occupants to die as the result of a road crash.

*

In 1969, a plaque was unveiled at the site of the accident to mark the event’s 70th anniversary.

Its message is simple.

‘Take Heed’…

Memorial at the site of the Harrow accident

Cold War London. Part Two; Bunker Mentality

The spying that went on in London and other cities was all part of a vast, complex game; an exercise in which the two mighty superpowers strived to gain the upperhand over one another.

Thankfully (and amazingly) the conflict they anticpiated for some 40 years never came to fruition.

But what if the Cold War had suddenly become hot?

Mushroom cloud graffiti in Bermondsey

Authorities in both the East and West made preparations for a predicted Third World War; a conflict which would have almost certainly led to the use of nuclear weapons and slain civilization as we know it.

The British government were under no illusion- in a global nuclear war, London would have been a primary target.

As such, covert preperations were made; plans which sought to protect the upper echelons of government and maintain command over whatever ruins were left.

Most of these plans were, of course, carried out in utter secrecy. However, if you know where to look, evidence of these candlestine preperations can still be seen in London today.

*

‘Stompie’

First, let’s begin this tour with something a little out of the ordinary.

During the Cold War, East and West were locked in an arms race, both sides amassing vast stockpiles of the ultimate boys toys; everything from nuclear submarines to inter-continental ballistic missiles.

Thousands of tanks were also accumalated on each side of the divide; guns bristling and catterpillar tracks ready to rumble out in a head-to-head across the plains of Europe should war ever break out.

One such tank; a Soviet model, can be seen in London. Not in a museum as you might expect, but in a rather more unlikely setting…

The tank in question is a Russian ‘T34’, and it can be found on the junction of Mandela Way and Pages Walk; backstreets off of the Old Kent Road.

Stompie in situ

The tank has quite a chequered history. It saw active service during the ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968, when it was rolled out to suppress peaceful protests against the leadership of the USSR.

Some 27 years later, the tank was put to more creative use when it was brought to London and employed as an extra on a film version of Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’ (starring Ian Mckellen and featuring scenes filmed at Battersea Power Station).

After its thespian role, the tank was purchased by Russell Gray; a property developer. The story goes that Southwark Council had refused Gray permission to build upon the land he owned, so, as a sort of spiteful protest, Gray took the tank and plonked it down on the empty plot, where it remains to this day.

Over the past few years, the tank has provided a canvas for various street-artists; each one creating their own fetching design for the old Cold War relic. The tank is also nicknamed ‘Stompie’, in honour of Stompie Seipei, the 14 year old South African youth who was brutally murdered in Soweto in 1989.

*

‘The Kingsway Exchange’

Had the Cold War ever become hot, the reprucusions for the UK would have been grim to say the least.

As a small island, densely packed with cities and military instillations, sandwiched between the USA and the USSR, Britain would have been devastated in a nuclear war, the death toll running into tens of millions, with the less fortunate survivors suffering from horrendous burns, injuries and radiation sickness.

The authorities realised this of course, and many bunkers were constructed across the UK in preparation for a Third World War. The sole purpose of these deep-level shelters was to protect the machinery of government, both at a national and local level, and space in such strongholds was strictly reserved for a limited number of politicians and civil servants.

Having said that, the bureaucrats did have our interests at heart to some extent.

In 1980, they released a short booklet to the public, entitled ‘Protect and Survive’. Priced at 50p, the pamphlet suggested ways in which to safeguard oneself against nuclear blast and radioactive fallout; mainly by utilizing doors, tea-chests and cushions- rather like a child building an indoor den on a wet weekend!

Building a fallout refuge: illustration from Protect & Survive

A series of videos were also produced. However, unlike the Protect and Survive booklet, these were never released to the public and were only intended to be shown during a period of international crisis in which war appeared inevitable.

If such an occasion arose, normal TV programing would have been suspended, replaced by the BBC’s ‘Wartime Broadcasting Service’ in which the 20 videos would have been played on a constant loop. As you can see from the example below, they were grim, eerie and their unsettling electronic jingle, created by the BBC’s Radiophonic workshop (then based on Delaware Road, Maida Vale) would’ve done little to boost confidence.

Please click below to view:

Whilst we above ground struggled with makeshift protection and dinky, ‘Playschool’ esque advice, the privileged few would have been tucked up in their deep shelters, ready to bear witness to the end of civilisation as we knew it.

Although the majority of fortifications (such as the vast ‘Burlington’ complex in Wiltshire) were built in the countryside, evidence of bunker building can be spotted in London today; perhaps the most well-known amongst bunker-buffs being the ‘Kingsway Exchange.’

The Kingsway dates back to that other rapid period of shelter building; World War Two. It is formed by a series of long tunnels, stretching beneath Holborn, roughly in sync, and running below the London Underground’s Central line (apparently, the bunker is actually connected to Chancery Lane tube station via a private stair-case).

Evidence of the bunker is revealed in these ventilation shafts, which quietly stand guard as commuters rush by.

Evidence of the Kingsway Exchange bunker; vents on Newgate Street (left) and Holborn (right)

The Kingsway exchange was originally constructed towards the end of WWII in order to house government staff- civil servants from the Ministry of Works and London Civil Defence controllers. Experts from the ‘Special Operations Executive’ (a branch of M16, set up to help Resistance fighters battling the Nazis), were also granted office space here.

The squirriling away of these workers beside a busy tube station was not unique; General Eisenhower had his protected head-quarters located in a shelter beside Goodge Street station (just off of Tottenham Court Road).

After WWII, and with the emerging Cold War threat of atomic attack, the Kingsway was expanded and beefed up. Ownership of the bunker was transferred to the General Post Office (GPO) who, at that time, were also responsible for telecommunications.

A large telephone exchange was set-up deep within the complex and a large percentage of civilian calls made from London passed through here.

More covertly, the London terminal of ‘TAT 1’; a transatlantic telephone cable, linked to the United States was established in the secure tunnel. This came online in 1956.

Because of this important communication link, the Kingsway Exchange played a key part in providing the infamous ‘hotline’ which connected the White House to the Kremlin.

At its height, some 200 people worked in the Kingsway Exchange and in order to cater for this large workforce, the bunker contained a canteen and a bar- which claimed to be the deepest in the UK.

The fortification below Holborn also boasted its own artesian well, and fuel tanks capable of holding 22,000 gallons which meant, in the event of a nuclear strike, it could be locked down and run for up to six weeks.

Map showing the approximate location of the Kingsway Exchange

*

The GPO Tower

Back above ground, the GPO were also responsible for building a far more well-known London landmark- the ‘GPO Tower’ …. Otherwise known as the ‘Post Office Tower’ or, as it’s called today… the ‘B.T Tower’.

For some 15 years, the GPO Tower was the tallest building in London (superseded by the NatWest Tower) and remains a famous site today, visible from many parts of the city.

The GPO Tower was celebrated for its revolving restaurant (run by holiday-camp giant ‘Butlins’ no less!), which made one complete revolution every 22 minutes.

A film depicting the restaurant as it appeared in 1966 can be viewed below:

Sadly, due to security concerns, the restaurant was closed in 1980 and the public have been refused access to the landmark ever since (with the exception of the annual ‘Open House Weekend‘, when those wishing to visit must provide security details before entering a lottery-draw to win one of the coveted tickets).

The BT Tower today

Despite being firmly embedded as a household name and major London landmark towering over the city, there is something rather surprising about the GPO Tower….

Until 1993, it was classed as an official state secret!

This covert status meant that it was not allowed to appear on any map. Taking photographs was also a no-no, and its address on Maple Street in Fitzrovia, was classified.

Why was this?

Well, the GPO Tower was in fact a key link in a system known as the ‘microwave network’ (nothing to do with the type of microwave you use at home to serve up a ready-made curry of course!)

Right up until the 1980s, the microwave network was responsible for transmitting television signals and other data- some of it military. The arrangement comprised of a link of transmitters, stretched across the UK from north to south; with towers similar to the London GPO erected in Birmingham (at Snow Hill) and Manchester (in Heaton Park).

Being extremely secure, the system was also known by the codename, ‘Backbone’ and, in the event of a nuclear attack, the resilient network would have provided vital communications for the government.

Quite how this would have worked, I’m not so sure- considering the searing heat and 500mph blast wave unleashed by a nuclear weapon, it is doubtful that any buildings (or indeed people) would have been left standing…

The route of London Underground’s Victoria Line (also constructed in the 1960s), runs considerably close beneath the BT Tower, and urban legends abound suggesting that it is secretly connected in some way. As is Buckingham Palace… but I suppose that’s another story altogether….

*

‘Q- Whitehall’

Going back below ground, there is inevitabely a myriad of tunnels beneath Whitehall, the seat of government.

However, although the exsistence of such a complex is taken as red, the exact details on what exsists are a little shadier.

The most documented facility below Westminster is a series of tunnels known as ‘Q Whitehall.’

Like the Kingsway exchange, Q Whitehall began life in WW2, and was extended during the 1950s. Documents related to the Cold War extension are still classed as secret, and will not be made public until 2026.

Essentially though, the tunnels which make up the Q Whitehall network are service tunnels, carrying secure communication cables and connecting various government departments. It stretches all along Whitehall, right up to Trafalgar Square– in fact, one of the entry points to the system is rumoured to be via Craig’s Court; a tiny alleyway less than 200 feet away from the Square.

As the development of nuclear weapons progressed from atom bombs to hydrogen bombs, it began to dawn upon politicians that a major city centre would perhaps not be the safest place to be during a nuclear war. The main government war HQ was therefore established outside of London; moving to Corsham near Bath, where a truly vast bunker; a small, underground town, was established and was only declassified in 2004.

*

Pear Tree House

Although central government would have fled the capital in the event of a nuclear war, local authorities were expected to stay behind and take care of their boroughs. Each council was required to provide their own shelter; most of which would have been rather makeshift affairs, hastily set up in the basements of town halls and civic centres.

If a Third World War ever did break out, plans were drawn up which would have involved the UK being divided into regional sectors; each forming a mini-kingdom of sorts, where the controller would have wielded total power.

London was designated as ‘Region 5’ and, due to its size, was sub-divided into four different sectors, each with its own purpose built bunker- one in Wanstead (North-East group), one in Southall (North-West group; the bunker being built beneath a school no less), one in Cheam (South-West group) and one at Crystal Palace (South-East group).

If you know where to look, the Crystal Palace bunker is still clearly visible and is one of the most unusual buildings in London…

Built in 1966, the bunker sits right in the middle of the large, Central Hill Estate… and right beneath a block of flats! The land upon which it sits was reclaimed from an old, WW2 bomb crater, created by one of Hitler’s ‘V2’ rockets; the prelude to the more advanced intercontinental missiles, which both the USA and USSR had poised at each other during the Cold War.

The bunker beneath Pear Tree House

The flat-block is called ‘Pear Tree House’, and can be found tucked away on the corner of Hawke Road and Lunham Road. Eight, two-bedroom flats sit above the nuclear shelter- although, of course, none of the residents living in them would have been allowed access had the four-minute warning ever sounded.

Due to its blatant location, Pear Tree House attracted much attention from anti-nuclear groups, and was picketed by CND during the early 1980s; their protest posters plastered over the heavy blast doors.

Slightly more innocuous view of Pear Tree House…

The bunker remained active right up until 1993 and, by all accounts, little has changed inside, with paperwork strewn everwhere, and large, ominous bomb-plotting maps still tacked to the walls. The bunker’s communication aerials are also still in place, clearly visible on the block’s roof.

*

Kelvedon Hatch

Pear Tree House, along with the three other shelters located within the London region, would have been answerable to a much larger bunker, which lay some 20 miles outside the city, deep within an Essex wood.

This bunker was known as ‘Kelvedon Hatch’, and was built to accommodate some 600 people. Constructed in the early 1950s, the bunker eventually became known as the ‘Sub-Regional Headquarters’ for London.

Essentially, this meant that if a nuclear war had ever struck the UK, Kelvedon Hatch would have been in charge of governing whatever was left of the Capital.

The entrance to Kelvedon Hatch…disguised as a harmless looking bungalow

Once inside the ‘bungalow’, this is the long tunnel which would have led the fortunate few deep underground and into the safety of Kelvedon Hatch bunker

The fortified shelter (like other regional centres built around the UK), contained a fully kitted out BBC studio, from which the regional controller would have been able to broadcast instructions and information to survivors (although whether or not anyone above ground would have been alive to hear his words is debatable).

In the immediate hours following an attack, the broadcasts relayed from this subterranean BBC studio would have been pre-recorded and, in 2008, the National Archives declassified one such script. Taped in the 1970s, its words are chilling to say the least:

“This is the Wartime Broadcasting Service. This country has been attacked with nuclear weapons. Communications have been severely disrupted, and the number of casualties and the extent of the damage are not yet known. We shall bring you further information as soon as possible…

Kelvedon Hatch BBC studio

We shall repeat this broadcast in two hours’ time. Stay tuned to this wavelength, but switch your radios off now to save your batteries until we come on the air again. That is the end of this broadcast.”

A full audio recording recreated by the late Peter Donaldson– the trusted ‘Voice of Doom‘ who would’ve read the transcript for real- can be heard by clicking below:

*

Safely stowed away in Kelvedon Hatch, the ‘Sub-Regional Commander’ (in peacetime, a high-ranking, local government councillor) would have been granted absolute power following a nuclear strike.

Emergency powers would have granted them the power to control food stockpiles (i.e withholding it from those who were ill or badly injured and therefore unable to work), rationing other commodities such as fuel, and organising survivors into conscripted work gangs. These workers would have been ordered to carry out all manner of tasks amongst the radioactive ruins; no doubt one of the jobs being the disposal of the countless dead.

*

Due to the high number of fatalities expected, sites for the largest mass-burial sites in London since the 1666 plague were earmarked; one of them being identified in this leaflet from 1982 (which can be viewed in the Imperial War Museum):

Anti-nuclear leaflet on display at the Imperial War Museum, revealing plans for mass-graves on Clapham Common

The Commander would also have been granted full control over law and order and, if any unlucky survivors happened to be caught looting amongst the rubble of London, emergency powers would have permitted their execution by firing squad.

Kelvedon Hatch, along with the rest of the UK bunker infrastructure, remained active right up until the early 1990s, and regular exercises were held in the Essex stronghold, in which the chosen few would spend the odd weekend acting out dress-rehersals for WW3.

Today, Kelvedon Hatch (which is just outside the Essex commuter town of Brentwood) is open to the public as a museum. If you fancy a visit though, be warned… it is an exceptionally creepy place, not helped by the fact that many of its rooms and displays are peopled by rather disturbing mannequins!

Dummies in one of Kelvedon Hatch’s rooms… (image: Gordon Joly, Creative Commons Licence)

*

Thankfully of course, none of these sites were ever used for their intended purpose, and they now sit quietly in the background, oblivious to most people.

I’ll end this piece though with a chilling montage of how things could have turned out…

The brief clip below is taken from a BBC documentary entitled ‘A Guide to Armageddon.’

Broadcast in 1982 as part of the scientific programme, ‘QED’, the terrifying episode examined what would happen to London if a 1-megaton nuclear warhead was exploded above St Paul’s Cathedral.

Taken from the end credits and using WW2 photos and primitive (although convincing) special effects, the clip provides a chilling, imagined view of a nuclear-destroyed London.

Please click to view.

The full episode can be watched here.

Don’t have nightmares!