Every day, I’m guaranteed at least one job to one of London’s numerous main railway terminals; those huge cathedrals devoted to train travel which suck in and belch out thousands upon thousands of commuters, tourists and casual visitors on an hourly basis.

London’s rail termini are hectic places indeed, and dropping passengers off is always a chaotic, yet strangely predictable process which can be summarized thus:

1) If heading for one of the larger, more complex stations, it is often advisable to determine which of the various entrances or drop-off points you’re going to aim the cab for. Veteran taxi-riders (generally City workers and patrons of swish Pall Mall clubs) are always in the know and will make this task a lot easier for you:

“Victoria Station please, driver… the old Gatwick Express entrance”…

or

“I need to get to Victoria, mate; just by Shakes” (‘Shakes’ is common commuter slang for The Shakespeare; a pub just across from the station’s main entrance.

Another popular Victoria drop off is the “hole in the wall.”

Heading into Paddington Station

“Paddington Station, cabbie… drop us on Spring Street, will you?”

(I’m always relieved when I meet such knowledgeable passengers- these clued up people are all too aware of the logistical nightmare that is trying to get into Paddington Station- when approaching from the south, you are not allowed to turn right into the station… you have to drive past Paddington (often through thick traffic), take the next available turn onto ‘Bishop’s Bridge’ and then spin a u-turn; all time-consuming, meter-ticking stuff. This process can be avoided with a quick, simple drop-off on nearby Spring Street).

“Waterloo Station… I don’t want the main entrance- just by the steps is fine; I don’t mind walking up”

or…

“Waterloo please; I’m in a hurry. Run it through that cut-through…umm… you know; Cornish or something…”

“Cornwall Road and Alaska Street, Sir?”

“That’s the one!”

2) Once you’ve dodged and weaved your way through the traffic, the next task is to find a place where you can pull over and let your passenger out safely.

In an ideal world, where things are smooth and geared towards actually helping people go about their daily business in an efficient manner, this should be a relatively straight-forward task.

In London, of course, it is not.

Upon reaching a station, you are guaranteed to be confronted with an anarchic tangle of taxis, buses and cars; all temporarily pulled over any which way they can in order to execute the very same task you are currently battling to complete. Usually, this vehicular mess resembles a minor pile-up, and you have no option but to slide along and nudge in wherever you can.

If the passenger has luggage, then you quickly hop out and around the cab in order to lend a hand; a risky business considering the never-ending stream of other taxis, buses and cars which are still swarming past, trying to absorb themselves into the mess which you’ve just joined.

It is amazing just how heavy some suitcases (many of which bristle with airport tags from all over the world) can be, and I’ll often worry that my sandwiches, which I carry in a small pack beside me, have been squashed during transit!

3) Once the journey is complete, the final hurdle is to actually exit the station.

Again, this sounds (and, in terms of common sense, should be) fairly easy.

However, when you have to count out change and (if required) jot down time-consuming receipts (for passengers who, only moments before were fretting that they only have a few precious minutes in which to catch their train), this is a fraught process- mainly because of the other taxis, buses and cars which continue to pour behind in a metallic, diesel-shrouded fug, all impatient, all desperate to negotiate their way through.

I’ve lost count of the times I’ve had hot-headed horns blasting at me, or the times in which I’ve been blocked in and unable to manoeuvre out. Leaving stations is often a frantic process, and involves money being stuffed into my coat pocket and pens being hastily being tucked behind my ear or chucked on the dashboard; leaving a slap-dash mess to sort out when I finally escape the station and arrive at my first red-traffic light.

*

Gosh! Now that I’ve relieved that from my tightened chest, I can move on… and state something which I’ve always believed:

Mainly due to the stress-ridden environments in which they fester, London’s railway terminals are in fact truly neglected places; criminally overlooked and shockingly ignored.

When our trains are on time, we breeze through them, paying no attention to the building whatsoever.

When our trains are delayed, we sit around, stewing with hate, cursing everything we see around us; animosities focused on the nearest uniformed representative whom we perceive to be responsible for obstacles which, in reality, often lie many miles, many counties and many regional accents away down the line.

This is very sad indeed… you see, London’s main railway terminals are actually amazing, wonderful places; glorious pieces of architecture; vital components of the capital, with long histories and fascinating stories.

In this new series; ‘Tales From the Terminals’, I shall be writing all about these important buildings; discovering their backgrounds and hopefully sharing some interesting trivia….

*

I’ll begin this exploration with central London’s most westerly terminal:

PADDINGTON STATION

Paddington, which serves trains heading to and from the West Country, is one of London’s most historical stations.

The name, ‘Paddington’ is believed to derive from ‘Padda’; an Anglo-Saxon chieftain who, sometime after the Romans withdrew from Britain in 410 AD, settled his clan in the vicinity of what is now the area around the junction of the Edgware and Bayswater roads.

An artist’s (or, to be more accurate, my) impression of ‘Padda’- which probably isn’t very accurate!

Paddington station was originally a wooden structure, first opened in June 1838 as the London terminal of the Great Western Railway, eventually linking the capital to the bustling port of Bristol, some 120 miles away.

The Great Western railway line was masterminded by the genius engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel:

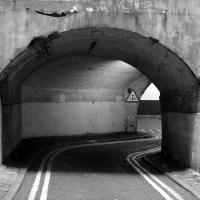

Isambard’s French-born father, Marc Brunel, had also been an engineer- responsible for pioneering the very first tunnel to be burrowed beneath the River Thames (the tunnel is still in use today; now part of the London Overground network, providing a passage for trains between Wapping and Rotherhithe. Above ground, at Rotherhithe, you can visit the Brunel Museum).

In 1833, the Great Western Railway appointed Isambard Kingdom Brunel as their chief engineer, granting him the huge responsibility of creating their planned railway line…. Quite a feat, considering Isambard was only 27 years old at the time!

*

Brunel was a true workaholic.

Setting to work on the task at hand and using a horse and cart as his main transportation, the young engineer surveyed the entire route on his own; a task which he completed within just 3 months.

Brunel was a keen visionary, and he regarded the London to Bristol railway route as the first section of a wider network, ultimately linking London’s Paddington to New York City- the idea being that passengers would travel to Bristol and board a transatlantic steamer (such as The SS Great Britain steam ship- also built by Brunel), which would then whisk them across the ocean.

Statue of Brunel situated at Paddington Station beside Departures Road. The great engineer also has a statue in Bristol (crafted by the same sculptor), both of which were unveiled in May 1982

*

The building of the Great Western Railway was far from easy, necessitating the construction of numerous bridges, viaducts, cuttings and tunnels (including the 2-mile long ‘Box Tunnel’ near Bath; the longest railway tunnel in the world when it first opened).

However, Brunel and his huge team of tough, hard-working navvies were more than capable of the task, and they had the first section open to trains within three years.

So smooth was the route, that the Great Western Railway soon gained the nickname, ‘Brunel’s Billiard Table.’

*

It was at Paddington Station, in 1842, that Queen Victoria arrived after her first ever railway journey, something which would still have been quite a novelty at the time. The Queen travelled from Slough… yep; the very same Slough which was the setting for the BBC comedy, ‘The Office’. Many forget that Slough is actually rather close to Windsor Castle…

Queen Victoria’s engine driver on that historic trip must have really put his foot down, as the trip took a mere 23 minutes at an average speed of 44mph.

The Queen’s husband, Prince Albert, wasn’t too happy with the driver’s speed-demonic ways and, after disembarking at Paddington, he scolded the driver with the words; “Not so fast next time, Mr Conductor”!

Being conveniently placed between Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace, Paddington Station was well suited to Royal travel, and it was a role which the Great Western Railway were keen to encourage. A royal waiting room; octagonal in shape and lavishly decorated, was therefore built at Paddington Station, and was used by the Royal family right up until the outbreak of WWII.

Today, the waiting room once patronised by Kings and Queens, now serves as the first class waiting lounge.

*

Paddington Station, as we see and use it today, was another Isambard Kingdom Brunel creation, built between 1850 and 1854.

For the beautiful glass roof, Brunel took inspiration from the mighty ‘Crystal Palace’ display venue, which was a contemporary piece of architecture at the time, having opened for the ‘Great Exhibition’ in 1851.

Brunel’s new station was faithfully captured in the 1862 painting, ‘The Railway Station’ by Yorkshire born artist, William Powell Frith.

In his day, Frith was incredibly popular, and large crowds flocked to see his works; The Railway Station being one of his most celebrated.

It was displayed at a gallery on the Haymarket (very close to Trafalgar Square); an exhibition which attracted 21,150 eager visitors; all of whom paid a shilling to study the painting’s many quirks and characters. Contemporary sources reported that Frith was paid somewhere between £8700 and £9000 to create the piece; a fee almost unheard of at the time. Today, the painting is owned by the University of London’s Royal Holloway College.

*

Paddington Station is notable for playing a key role in the creation of the Metropolitan Railway; the great-grandfather of the London Underground (and the world’s very first subway system).

By the 1850s, London’s roads were choked with traffic (sound familiar?!) and, as a result, plan were drawn up to run a railway line beneath the city streets; primarily in order to link London’s major railway termini.

Although many in Victorian society regarded such plans as being rather eccentric and unorthodox, the Great Western Railway agreed to help fund the project and, in return, Paddington Station was made the western terminus of the new-fangled subway.

The world’s first underground railway, linking Paddington in the west to Farringdon in the east, opened in January 1863.

The early London Underground lines were a lot shallower than the later deep-level ‘tubes’ (such as the Bakerloo, Piccadilly and Northern lines), and were built just below street-level using a construction method known as ‘cut and cover.’

In those early days, the trains used on the London Underground were good old fashioned steam engines; noisy, clunking mechanical beasts with a furnace blazing in their guts.

Because they ran underground through confined spaces, the clamour and choking smoke from these engines was intense to say the least. As The Times noted in 1864, a year after the Metropolitan Railway opened;

“it is an insult to common sense to suppose that people would ever prefer to be driven amid palpable darkness through the foul subsoil of London.”

An early, steam-driven, London Underground Train (which can be seen at the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden)

Despite early concerns, the world’s first underground line proved to be a roaring success.

Steam engines were used in the underground tunnels right up until the early 20th century (and were still in service on the Metropolitan line’s outer branches- such as Amersham- right up until 1961).

Today, the historic, trailblazing tunnels which emanate out of Paddington still carry 1,000s upon 1,000s of passengers every day; albeit in cleaner, quieter electric trains!

*

With such a long history, it is perhaps inevitable that Paddington has had to suffer some tragedy during its lifetime.

During WWII, railway lines (which were strategically important in carrying troops and vital supplies) were a key target for Nazi bombers. In 1941, Paddington Station was hit by a particularly powerful parachute-deployed bomb.

The resulting explosion led to a large section of Paddington’s offices being destroyed- leaving a broad gap which is still clearly visible between the buildings today:

More recently, early on 5th October 1999, The Paddington Train Crash occurred a short distance outside the station, in the vicinity of Ladbroke Grove. The accident involved an intercity train, heading from Cheltenham into Paddington, colliding with a smaller, local train, which had mistakenly passed through a red signal.

The resulting crash resulted in a huge fireball in which 31 people lost their lives and some 250 were seriously injured.

Much of the blame for the tragedy lay with ‘Signal SN109’; a set of lights which perched on a particularly high gantry and was notoriously difficult for train drivers to see, especially in the bright sunlight of a crisp, autumn morning.

Thankfully this problem has now been rectified, and such incidents are exceptionally rare on the British railway network.

*

Of course, no account of Paddington Station is complete without mentioning its most famous namesake; the loveable character, Paddington Bear who was first created by author, Michael Bond in 1958.

As the story goes, the little bear, who hails from deepest, darkest Peru, has been sent to England by his Great Aunt Lucy, who is rather elderly and has been forced to enter a home for retired bears, thus making her unable to care for her nephew any longer.

Upon his arrival in England, the refugee bear finds himself at Paddington Station, where he is discovered by the kindly Mr and Mrs Brown.

Upon spotting a tag around the bear’s neck, which pleads, “Please look after his bear…”, the Browns decide to adopt the stray, naming him ‘Paddington’ after the very station in which he was found.

Paddington moves into the Browns’ home; at ’32 Windsor Gardens’ (Windsor Gardens is indeed a real road, and is situated quite close to Paddington Station, just off of the Harrow Road. However, it is little more than a short, stubby dead-end, and there is nothing much to see) and all manner of adventures ensue.

Today, a bronze sculpture of Paddington Bear (based upon the original 1950s drawings) sits within the station. Being life-sized, it is naturally quite small and tricky to find! If you wish to share a seat with the little bear, head for the area towards the rear of the station; you’ll find him hiding amongst the shops, not far from a set of escalators.

Over the years, there have been many Paddington Bear stories, and the furry, railway-station foundling has also starred in a number of TV spin offs; the most well-known being the distinctive BBC adaptation which aired in the 1970s and 1980s.

*

Here, in all its glory, is the very first episode of the BBC series, which dates from 1975.

This is where we first meet the little bear, and much of the action is set within Paddington Station (keep an eye out for the grumpy London cabbie towards the end of the cartoon who appears to be the first ever person in the UK to receive Paddington Bear’s infamous ‘hard stare’! Just for the record, I personally would never dream of charging “sixpence extra” for a bear… let alone an extra nine pence for “sticky bears”!)

Gosh what a kind and helpful cabbie you are! So many times I have struggled with luggage whilst the cab driver simply looks the other way.

Always glad to be of service! Sorry to hear you’ve had some bad experiences.

I’m so glad I found you through Smitten by Britain. Your stories are marvelous! And I do love Paddington Bear, so that clip was a treat. Wish I had time to read more just now, but I’ll have to come back tomorrow. Cheers!

That’s very kind of you, Jean! Hope you make it back soon, you’re always welcome!

Hello, I read on your profile that you studied english literarure. Well, I am a student too, right now of English and Creative Writing and I am writing a creative Dissertation, a story about a london taxi driver. I was wondering if I might have your permission to quote your blog in my commentary and biblipgraphy, and also if you might awnser some interview questions that I have. Your prose is strong and captivating. There was a comment a while back that you should consider a book… I think thats not a bad idea at all. 🙂

Anyway, if you could let me know about quoting you and interview questions.

Thanks.

Can’t spell Biblography, thats embarrasing.

Thanks for this.. I recognize how hard it must be to pull a comprehensive history of such a place and summarize it within a brief page. A lot of the post reminds me of New York’s historic train engineering as well,

Grand Central Station right in the middle of New York comes to mind as a relative carbon copy of Paddington, with it’s cut and cover, its smoke in the tunnels, and its accident.. it’s an inspiration, and I should get on the new york equivalent of your post.

Thanks for those kind words, Noah. Hope the cab trade in New York is going well for you at the moment.

Great Post! I found Paddington Station a treat. It was easy to navigate even in heavy crowds. I looked for the statue of Paddington Bear and love the pictures I was able to take. Now thanks to you I know much more about the station and the statue of the Man in the Chair as we called it! Thank You

[…] heavily monitored, making it much more functional and efficient. I verified this when hopping on the Paddington Underground Station, seeing all the Londoners, business men and women, families, and other tourists hopping on the […]