Tales From the Terminals: Waterloo Station (Part 1)

Handling an average of over 90 million passengers a year, Waterloo which lies close to London’s South Bank, is the UK’s largest railway station.

The origins of Waterloo Station stretch back to 1838 with the founding of the London and Southampton Railway, a company established to provide an important rail link between the capital and the docks at Southampton.

Originally designed with freight in mind, the London end of the new connection to the south coast opened on 21st May 1838 at Nine Elms, an area close to a wharf on the southern shore of the Thames- some distance away from the present Waterloo station.

Built in the neo-classical style, the station building at Nine Elms was designed by Sir William Tite, the same architect who designed the Royal Exchange which stands opposite the Bank of England.

Although a convenient place for shifting cargo, the Nine Elms location proved to be most inconvenient for the growing numbers of passengers who were beginning to use the line for trips into London.

There were pleasure gardens at nearby Vauxhall which were a popular destination, but for those wishing to travel onwards to Westminster and the City things were a real hassle with trips having to be completed by boat (which involved a lengthy wait) or by road (which involved high costs due to the existence of turnpike tolls).

The former Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens- the only London landmark which was easily accessible from Nine Elms station (image: History Today).

As the London Illustrated News reported at the time, “the distance of the South Western’s metropolitan terminus from the heart of London has been a subject of complaint from the first opening of the line.”

Moving On

Realising that their railway fell short- and that there was of course more money to be made- the company (now renamed the London and South Western Railway) decided to extend the line approximately 2 miles north across Lambeth Marsh in a project costing £800,000- approximately £35 million in today’s money.

The site marked for the new terminal was described as being “vacant ground, to a great extent occupied as hay-stalls and cow-yards and by dung-heaps, and similar nuisances” which lay close to the southern foot of the recently opened Waterloo Bridge.

A lost ‘Trafalgar Station’?

The station’s South Bank site was a plan B option- what developers had really wanted was to cross the Thames and build a station right opposite what was then a pretty much brand new Trafalgar Square.

The snag with this however was that the Duke of Northumberland’s mansion stood in the way and he refused to release the land… a 170 year old decision which still brings cabbies plenty of quick fares across the river during the rush hour!

Northumberland House pictured in 1753. Note the statue of Charles I (in the bottom right hand corner) which remains in the same position today. The mansion was demolished in 1874 and is now covered by Northumberland Avenue.

Had the site been allowed it is quite possible that the LSWR’s terminal would have been named ‘Trafalgar Station‘… either way, a name in honor of one of the great victories of the Napoleonic Wars was inevitable!

The station that never was… if plans had come to fruition, the LSWR’s terminal would have stood right opposite Trafalgar Square.

Bridging the Bogs

In order to traverse the boggy ground the extension required the construction of a brick viaduct comprising 290 arches- very similar to the London and Greenwich Railway which was constructed on the opposite side of the capital during the same era.

Images of the Nine Elms to Waterloo arches from 1840 (top image- ‘Church Street’- now Lambeth Road. Bottom image- Westminster Bridge Road. (Images: London Illustrated News).

Whilst building the viaduct from Nine Elms to Waterloo the tradesmen certainly didn’t hang around. The arch across Miles Street for example is said to have taken just 45 hours to complete from scratch, despite being at a tricky angle and requiring some 90,000 bricks!

The LSWR turned again to Sir William Tite to design their new terminal and, like the track extension, the station had to be built upon a series of arches in order to rise above the soggy earth; a high-rise position which is still evident to this day.

I wonder how many of the passengers in my cab who asked to be dropped at “Waterloo steps” realise why they have to huff and puff up such a steep flight in order to catch their train….

Named ‘Waterloo Bridge Station’, the new terminal, with a 600ft façade facing York Road, opened to the public on the 11th July 1848 with just three platforms and 14 trains a day.

York Road today- The site of Waterloo’s original facade is now occupied by late 20th century office blocks (image: Google).

Originally, the station was never intended to be the end of the line- it was planned that the rails would be forged onwards, right into the heart of the financial square mile.

As we can see today of course, this vision was never realised (with the exception of an underground link which we will come to later) and the site was officially renamed ‘Waterloo Station’ in 1886.

*

The Decline of Nine Elms

With the opening of the Waterloo terminal, the original Nine Elms Station closed to passengers in 1848.

A vast freight yard and wagon works flourished on the site but suffered heavy damage during WWII from which it never fully recovered. A clip of the site as it appeared in the mid-1960s, during the last days of steam, can be seen below (please click to view).

In the early 1950s, it was proposed that Tite’s surviving Nine Elms station building would make an ideal home for a planned National Railway Museum. However, British Rail refused to release the land and the museum eventually found a very worthy home in the beautiful city of York.

The Nine Elms building was sadly demolished in the 1960s, paving the way for the construction of New Covent Garden Market which still occupies the site today, maintaining the location’s historical link as a major hub for shifting goods into the capital.

In a few years’ time, the area will also provide a home for the new American Embassy.

*

Back at Waterloo

With the addition of connections to different railway companies, Waterloo station expanded in a messy, chaotic way throughout the Victorian period.

As new platforms were added they gained eccentric nicknames such as ‘Cyprus Station’ and ‘Khartoum Station’; each with their own entrance, booking office and Hackney Carriage rank.

Some platform numbers were duplicated whilst others weren’t labelled at all which created considerable confusion. In 1889, this bizarre situation was satirized by Jerome K. Jerome in ‘Three Men in a Boat’:

“We got to Waterloo at eleven and asked where the eleven-five started from. Of course, nobody knew; nobody at Waterloo ever does know where a train is going to start from, or where a train when it does start is going to… the porter who took our things thought it would go from number two platform, while another porter, with whom he discussed the question, had heard a rumour that it would go from number one. The station-master on the other hand, was convinced it would start from the local.”

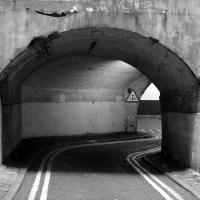

There was even a set of tracks which cut right through the pedestrian concourse and out through an arch towards what is now Waterloo East station.

Even by Victorian standards this rail link was a health and safety nightmare and was rarely used.

However, this curious set-up was still prominent enough to feature in H.G Wells’ 1898 classic, ‘War of the Worlds’ in a scene which describes troops departing Waterloo for Surrey in preparation for a clash with the Martian invaders.

“About five o’clock the gathering crowd in the station was immensely excited by the opening of the line of communication between the South-Eastern and South-Western stations, and the passage of carriage-trucks bearing huge guns and carriages crammed with soldiers.

These were the guns that were brought up from Woolwich and Chatham to cover Kingston. There was an exchange of pleasantries: ‘You’ll get eaten!’ ‘We’re the beast-tamers!” and so forth.”

The unusual bridge which linked the two stations is still in place and can be seen stretching over Waterloo Road.

Until relatively recently, it was used as a pedestrian link before being replaced by a more modern walkway (the grey, tube structure which can be seen running above).

TO BE CONTINUED…

Cold War London. Part One; The Spy Game

Secrets are a constant source of fascination for people, especially when undisclosed mysteries are lurking right there beneath your feet or nose.

Taking my previous post about the Berlin Wall into consideration, and with the big screen adaptation of John Le Carre’s espionage masterpiece, ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’ currently playing in cinemas, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at some sites in London which have a murky connection to the Cold War; a period in recent history which has always held a great fascination for me.

*

Being one of the most important cities in the West, London played host to many spies during the Cold War and, in a such a vast, sprawling city, in the days before CCTV cameras sprouted up everywhere like a plague of mushrooms, London was a city very conducive for the execution of undercover activities….

In London, there were all manner of places where Soviet KGB spies would meet up with their contacts.

An important part of their shadowy network were the various ‘dead letter boxes’ (also known in spy circles by the abbreviation ‘DLB’); discreet locations where important packages could be left and collected.

The most well documented of these was set up in the Brompton Oratory; a famous Roman Catholic Church, five minutes’ walk away from Harrods.

As you walk in through the main entrance, there is a marble pillar to the right, and it is behind this that agents used to hide their top-secret notes and parcels.

Brompton Oratory, Knightsbridge

The fact that the Brompton Oratory DLB was situated so close to Harrods is no coincidence.

If an agent conducting his covert business at the church had reason to believe he was being followed, he simply headed for the world-famous department store and lost the tail. With Harrods spread over a five-acre site, composed of some 330 departments and with numerous entrances and exits, losing a would-be tracker was relatively simple…

*

Another dead letter box was to be found in Bloomsbury; on Coram’s Fields, not far from Russell Square.

Coram’s Fields is noted for being child-friendly, especially considering its links to the ‘Foundling Hospital’ (an orphanage was established here in the 1700s) and its proximity to Great Ormond Street children’s hospital.

Coram’s Fields, Bloomsbury

In the early 1980s, Oleg Gordievsky (an undercover agent, based at the Soviet Embassy in London), took his young daughters to play in the park. Whilst there, he nipped over to the DLB and causally stowed away a brick amongst some shrubbery. It was no ordinary brick though for two reasons.

1- It was a false brick and

2- It contained a cool £8,000!

Oleg tucked this valuable hoard away so it could later be collected by a fellow agent who was in trouble and needed cash.

*

Not many people realise that, during the autumn of 1983, the world came the closest it’s been to WW3 since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

A combination of events- including the Soviet shoot-down of Korean Airlines Flight 007, the deployment of cruise missiles in Western Europe (most famously at Greenham Common), a terrifying false alarm on the Soviet’s missile warning system (thankfully overridden by chronically overlooked hero, Stanislav Petrov) and a NATO war exercise codenamed ‘Abel-Archer 83’, which the Soviets feared was a prelude to a real attack, almost culminated in triggering a global nuclear war.

At the time, however, the public were oblivious to this, blissfully unaware of the politicking and lunacy which was going on behind the progressively absurd scenes.

In the months leading up to crisis, the ageing and increasingly paranoid Soviet leadership had convinced themselves that war was imminent.

Under the guidance of Yuri Andropov, they therefore initiated ‘Operation Ryan’; an intelligence gathering mission with the key aim of pin-pointing the exact date when the West were planning to launch their attack on the Soviet Union. Operation Ryan’s motto was stark, yet simple: “Don’t miss it.”

Your Andropov pictured in August 1983

Russian agents in London were instructed to monitor all sorts of bizarre activity. Were calls for blood donors on the increase? Was meat being stockpiled at Smithfield market?

The observation of key figures and buildings was also ordered… so, every evening during the operation, a KGB agent would lurk outside the Ministry of Defence on Whitehall.

His task?

To count the number of lights which remained shining through the huge building’s many windows.

The rather roundabout theory went that, if lights were on late at night, then that suggested the high honchos were still at work, burning the candle at both ends as they penned up their plans for the Third World War.

Funnily enough though, the KGB didn’t appear to stop and consider what was probably the true reason for the lights beaming in the the Ministry of Defence late at night:

The office cleaners were hard at work!

The Ministry of Defence at night in 2011… lights ablaze, just as they were in 1983, when KGB agents would stand outside counting them!

*

Of course, one of the hazards of being a spy was the possibility of capture.

This is Wormwood Scrubs (names don’t get grimmer than that); one of London’s most notorious prisons:

Wormwood Scrubs Prison

In 1966, it was the scene of an audacious and successful prison-break.

A few years before, in 1961, a spy by the name of George Blake had been found guilty at the Old Bailey of breaching the Official Secrets Act. He’d betrayed dozens of British agents to the Soviets, a number of whom were believed executed as a result.

Blake was sentenced to 42 years imprisonment- a record at the time; being the longest sentence ever dished out in a British court.

Whilst in prison, Blake met Sean Bourke, Michael Randle and Pat Pottle; the latter two being passionate anti-nuclear protestors. Their sentences were far briefer and, once out, they conspired to free George Blake.

George Blake

A walkie-talkie was smuggled into Wormwood Scrubs, enabling the group to hatch a plan.

The plot was simple, but daring. One evening, whilst most of the inmates were watching their weekly movie, Blake sneaked off and squeezed through a large, gothic window at the end of the wing (a small pane having been previously been loosened for the purpose).

He then dropped 20 ft. and scrambled over the outer wall with the aid of ladder, which had been hurled over by his counterparts… the ladder, was extremely makeshift- its rungs made up from size 13 knitting needles. Must have been a pretty precarious scramble!

Once over the wall, he was met by Bourke, who sped him away in a getaway car. Blake had broken his wrist during the escape and, once in the car, he blacked out.

Blake spent the next few weeks being transferred between safe houses around London (one of the known places being an apartment on Willow Road in Hampstead), before being finally smuggled into Europe where, at an East German checkpoint, he entered the Soviet Union.

Sean Bourke died in 1982, but Michael Randle and Pat Pottle were tried for their part in the escape in 1991. They argued that, although they did not agree with Blake’s espionage activities, they found his lengthy sentence “inhumane.”

They were found not guilty on all counts.

To this day, George Blake still lives in Russia. In 2007, on the occasion of his 85th birthday (and long after the end of the Cold War), Blake was honoured by Vladimir Putin with a gala celebration, where he was awarded the ‘Order of Friendship’ in thanks for his services to Russian intelligence!

*

George Blake fled to the USSR.

Georgi Markov, however-a Bulgarian writer and dissident- did quite the opposite, defecting to the West in 1969; first to Italy, and then onto London in 1972.

Markov had been a fierce opponent of the Communist regime, his views expressed through novels such as ‘A Portrait of my Double’ and ‘The Women of Warsaw.’ Because of his anti-communist sentiments, Markov’s works were banned throughout the East.

However, once in the West, Markov was free to pursue his critique of the regime.

Such actions ensured that Markov remained a major thorn in the side of the East and, by 1977, the leader of Bulgaria’s Communist party- Zhivkov Todor- had come to the stark conclusion that Markov needed silencing.

Georgi Markov; Bulgarian writer and dissident

*

On the 7thSeptember 1978, Georgi Markov carried out his usual commuting routine; parking his car on London’s Southbank, before heading for Waterloo Bridge, where he would take a short bus ride to his BBC office in Bush House.

Whilst he waited at the north-bound bus stop on Waterloo Bridge, cars and commuters swarming past, Markov suddenly felt a sharp sting in his leg.

Looking up, he noticed a man nearby, picking up an umbrella from the pavement. The stranger made a hurried apology, before quickly flagging down a taxi and exiting the scene (you never do know why you’re going to pick up….)

The southern end of Waterloo Bridge; site of the bus-stop where Georgi Markov was stabbed with an improvised umbrella

By the time he arrived at work, Markov was in considerable pain, and a small red mark had appeared on his leg. By the evening, he’d developed a fever and was admitted to St James’s Hospital in Balham (a hospital which, like so many others, no longer exists, and has given way to a block of apartments).

Upon examination, doctors at St James’s discovered a tiny puncture wound- about 2mm in diameter- on Markov’s leg. Septicaemia was diagnosed and, three days later, Georgi Markov was dead, as was his voice of dissent. He was 49 years old.

When the post-mortem was carried out, the true culprit responsible for the writer’s death was discovered.

A tiny, metal sphere- no bigger than a pinhead- was located in Markov’s leg wound. Two minute holes were bored into the little pellet and, after being sent to the government’s chemical research centre at Porton Down, it was concluded that the tiny sphere had contained a lethal dose of ricin, slowly released into Georgi’s bloodstream after being injected by an improvised umbrella.

Sources speculate that Georgi Markov’s assassin was one Francesco Gullino; an agent who posed as an art-dealer and went by a very London-esque codename:

‘Agent Piccadilly.’

‘Agent Piccadilly’ (Francesco Gullino) & the ricin pellet which some believe he was responsible for injecting into Georgi Makov on Waterloo Bridge in 1978

To be continued…

*

Please click here for Part Two