An Atrocity at the Adelphi

Located on the Strand and originally dating back to 1806, the Adelphi Theatre (currently hosting a run of ‘The Bodyguard’) harbours a rather sinister story…

The Adelphi Theatre

At the centre of this drama is William Terriss; a Londoner born in 1847 who was educated at a school attached to Tottenham’s Bruce Castle.

William Terriss pictured in 1896.

William’s early shots at establishing a career were adventurous to say the least, including stints in the Falklands where he farmed sheep, the States where he mined silver and Bengal where he cultivated tea.

After this incredibly varied graft, William eventually returned to London in 1886 where, being a good-looking chap with a dashing manner and harmonic voice, he decided to give the acting game a go.

William Terriss in acting mode (image: Wikipedia)

When it came to treading the boards, the former Tottenham lad proved an instant success, quickly achieving a level of fame which was on a par with today’s celebrity culture.

Along with his immense popularity, Terriss was also noted for his tireless generosity and capacity to help others.

An extreme example of this was demonstrated when he turned up for work at the Adelphi one evening dripping wet. William made no mention of why he was in such a soaked state and it was only later that his puzzled colleagues discovered the reason… the actor had plunged into the Thames to rescue a drowning child.

*

One person in particular that William bent over backwards to help was Richard Archer Prince; a young actor struggling to make the big time.

Kind hearted as ever, William Terriss took the wannabe thespian under his wing, lending him cash when required and securing bit-parts in his shows.

The Adelphi in days of old…

Prince however was an erratic character whom many others steered well clear of. A heavy drinker, his violent unpredictability earned him a dubious nickname…‘Mad Archer.’

Despite the support from his mentor, Prince gradually became extremely envious and fiercely resentful of Terriss. Fantasising that he was the better artist, Mad Archer despised the fact that his benefactor always received top billing.

These dangerous delusions came to a tragic head in the December of 1897…

On the evening of the 16th, a horse-drawn Hansom cab rattled along the cobbles of Maiden Lane, coming to a halt outside the Adelphi’s rear stage door.

Covent Garden’s Maiden Lane…

The punter on board was William Terriss, who stepped out, paid the cabbie and dug the special key out of his cloak which would provide access to the theatre’s private entrance.

The Adelphi stage door on Maiden Lane.

Before he had a chance to unlock the door however, a figure pounced out of the gas-lit shadows… it was Mad Archer himself who, without warning, launched at William, stabbing the Victorian celeb several times.

Following the scuffle, a crowd quickly gathered and the famous performer was rushed inside the theatre.

Doctors were sent for from nearby Charing Cross Hospital (now a police station on Agar Street), but it was to no avail- William Terriss was dead within minutes.

The former Charing Cross Hospital (image: Google Streetview0

Restrained by the growing mob, the murderer made no attempt to escape and sat quietly awaiting his arrest. He was marched off to a cell on Bow Street, apparently telling the cops that Terriss “knew what to expect from me.”

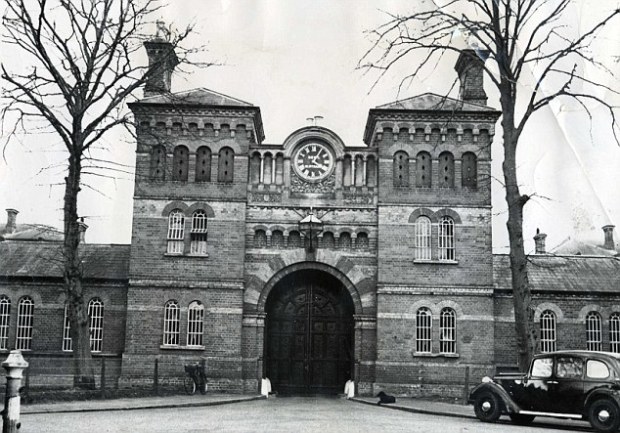

Bow Street court and police station (image: Old Bailey online)

The murder shook Victorian society and, at the trial, Prince made the baffling claim that William had prevented him from advancing his career.

The jury were quick to find the culprit guilty- although he was spared the noose thanks to the conclusion that he was not of sound mind.

The disturbed bit-player spent the remainder of his days incarcerated in the Broadmoor asylum for the criminally insane, where it is said he liked to write and produce plays in which he always placed himself in the leading role…

Broadmoor Psychiatric Prison, Berkshire…

*

William Terriss was laid to rest at Brompton Cemetery; the service attracting over 50,000 mourning admirers.

Brompton Cemetery (image: Wikipedia).

Legend has it that his ghost now haunts Covent Garden tube station (in William’s day, his favourite bakery stood on the Long Acre site, the station being built 10 years after the murder).

Covent Garden Tube station, Long Acre.

The first sighting of the phantom was reported in 1955, when a ticket collector allegedly spotted the shimmering actor, donned in an opera cloak with cane In hand, pass through a closed door.

Over the next few years, the ghost was spied on numerous occasions in the staff cafeteria…and, although the last recorded sighting was in 1972, tube workers still sometimes report bizarre, unexplained noises in the dead of night….

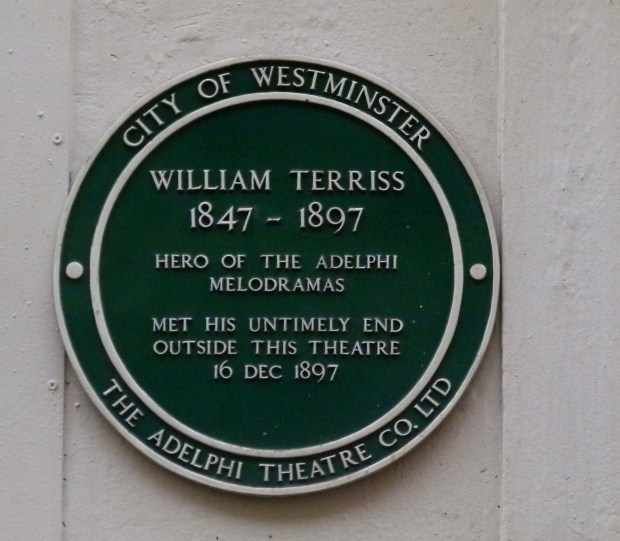

Plaque on Maiden Lane commemorating the murder of William Terriss.

Logie Baird’s London (Part Two)

Eureka!

Toiling away above Frith Street, with financial help from his family and a £200 donation from a private benefactor, John Logie Baird struggled with his invention for many months.

For his experiments, he used an old ventriloquist’s dummy’s head; a character whom he nicknamed ‘Stooky Bill’.

‘Stooky Bill’ one of the earliest stars of television!

However, try as he might, the Scottish inventor just could not get the image of his plaster prop to appear on the televisor’s wee screen.

As autumn set in, Logie Baird had been at Frith Street for almost a year, yet his invention seemed to be going nowhere.

John Logie Baird, hard at work in his Frith Street lab

But then, on Friday 2nd October 1925, the breakthrough moment came:

“Funds were going down, the situation was becoming desperate and we were down to our last £30 when at last, one Friday… everything functioned properly.

The image of Stooky Bill formed itself on the screen with what appeared to me almost unbelievable clarity. I had got it! I could scarcely believe my eyes and felt myself shaking with excitement.”

How Stooky Bill would have appeared on screen (reconstruction)

Almost immediately, Logie Baird wanted to test his televisor on a living, breathing human being.

In a sudden burst of energy, he dashed downstairs which, at that time, was home to an office belonging to a Mr Cross. Logie Baird asked if he could quickly borrow the office boy; William Taynton.

William was quickly hauled upstairs and plonked in front of the camera. Wasting no time, John Logie Baird dashed over to the viewing screen… only to find it blank.

What the inventor had failed to realise in his haste was that young William, being rather scared by the bright lights and rapidly whirring discs, had shied away from the camera!

Persuasion was on hand though- in the form of half a crown. Taking this handsome payment in hand, William Taynton diligently sat where required… as the flickering image appeared on the screen, the young lad on the other side of the camera probably didn’t realise that he was going down in history as the first ever real-life T.V star!

Reconstruction of William Taynton on the televisor’s screen

Shortly after this euphoric success, there was a knock at Logie Baird’s door… it was a group of Soho prostitutes who, having glimpsed the strange machine through a window, has mistaken it for a telescope- and demanded to know why the Scotsman was spying on them!

Going Live

Within a few months, John Logie Baird was ready to demonstrate his televisor to the public.

On the 26th January 1926, at Frith Street, he gave the first showing to a group of guests from the Royal Institution. The demo, also beamed to guests at Olympia and at premises on Savoy Hill (behind the Savoy Hotel), included transmitted images of Stooky Bill and also of a real person.

Today, a blue plaque at Frith Street commemorates this event:

Although the showing was a success, one critic from the Royal Institution, clearly not grasping the ground-breaking nature of the event he’d just witnessed, felt compelled to ask; “well… what’s the good of it? What useful purpose will it serve?”

The first ever photo of a broadcasted image. Taken c. 1926, the person being filmed was Oliver Hutchinson; Logie Baird’s business partner

Following the first public demonstration, ‘Baird Television Limited’ was established, its headquarters moving a short distance from Frith Street to 133 Long Acre in Covent Garden.

Further experiments were carried out at the new studio, each more ambitious than the last.

In 1927 John Logie Baird successfully broadcast test images to his native Scotland; the receiving end being a televisor set based at Glasgow’s Grand Central Hotel.

The following year, he also succeeded in beaming grainy images (of a man and woman sitting in his studio) across the Atlantic to New York.

Experiments with colour and even 3D were also conducted.

With these advancements, John Logie Baird knew that the time was ready to begin broadcasting to the public.

In those days, the only broadcaster in the UK was the British Broadcasting Corporation; itself in its infancy (and, in those days of course, a radio station).

Logie Baird approached the BBC’s director, John Reith and, after some persuasion, managed to get the corporation to give the new technology a try.

Logie Baird had built a transmitter on the roof of his Long Acre premises, but he soon realised it would be too weak for his ambitions. He therefore needed to borrow one of the BBC’s aerials- known as ‘2LO’ which was located on the roof of Selfridges.

However, 2LO’s primary use was for radio broadcasts, so the BBC only granted Baird Broadcasting access to the transmitter between 11pm and mid-morning next day, when wireless broadcasting was off-air.

Selfridges continued to play an important role in the dawn of television when the first Baird ‘Televisor’ sets went on sale at the department store.

A ‘Baird Televisor’; one of the first ever television sets

With prices for the new equipment ranging from £20 to £150 (equivalent at the time to the price of a motor-car), only a handful of wealthy people in the London area were able to receive the new-fangled programmes.

In fact, for the very first broadcast, Logie Baird himself estimated that only 30 people were tuned in! One of this select group was the Prime Minister himself; Ramsay McDonald, who watched the historical moment from 10 Downing Street on a Televisor which had been presented as a gift from the Scottish inventor.

The very first programme was broadcast from Covent Garden’s Long Acre on the morning of 30th September 1929.

‘Baird Television’ title card

Due to transmitter limitations, the sound and vision had to be broadcast separately in two minute bursts; so the viewer would first see a silent, flickering image with the crackling sound following shortly afterwards. This split process would continue for the first six months of programming.

The very first televisual broadcast opened with a speech by Sydney Moseley; Logie Baird’s business manager and one of his most supportive friends.

The tiny audience would have seen Sydney, silent but mouthing words… followed two minutes later by the vocal segment:

“Ladies and Gentlemen: you are about to witness the first official test of television in this country from the studio of the Baird Television Development Company and transmitted from 2LO; the London Station of the British Broadcasting Corporation.”

A few more short speeches followed, and then the morning’s entertainment began. The schedule ran as follows:

11.16am. Sydney Howard: televised for two minutes.

11.18am. Sydney Howard: Comedy monologue.

11.20am. Miss Lulu Stanley: televised for two minutes.

11.22am. Miss Lulu Stanley: sang ‘He’s tall, and dark, and handsome’ followed by ‘Grandma’s proverbs.’

11.24am. Miss C King: televised for two minutes

11.26am. Miss C King sang ‘Mighty like a rose.’

Morning television in those days was clearly far more sophisticated than the dross on offer today!

Plaque on Long Acre commemorating the first ever televisual broadcast

On the 14th July 1930, Baird Television were finally able to broadcast the sound and vision together for the first time. The vehicle used for this demonstration was a short play called ‘The Man With the Flower in His Mouth’, which was written in 1922 by Italian playwright, Luigi Pirandello.

Chosen for its simplicity and small cast (considerations which were driven by the tiny televisor screen), the short play is essentially a philosophical conversation in a café between a businessman who has just missed his train and another fellow who is suffering from a cancerous throat.

A preview in the Times described the drama as being “a forbidding study of emotion in the shadow of death.”

The actors, who performed the play live at Long Acre, had to have their faces painted yellow, with navy blue shading around the eyes and nose. This bizarre makeup was intended to enhance their image on the shimmering receiving screens, which glowed a characteristic reddish-orange colour.

‘The Man With the Flower in His Mouth’ being broadcast live from the Covent Garden studio on Long Acre, 1930

In 1967, The Man with the Flower in His Mouth was painstakingly remade in an attempt to emulate what audiences back in 1930 would have seen. The recreation was supervised by the play’s original producer, and also includes the original artwork and gramophone music.

If you’re wondering what the box had to offer in those days, the whole play can be viewed below:

By late 1930, Baird Television’s Covent Garden studio was beaming 30 minutes of programmes in the morning; Monday to Friday and 30 minutes at midnight on Tuesdays and Fridays.

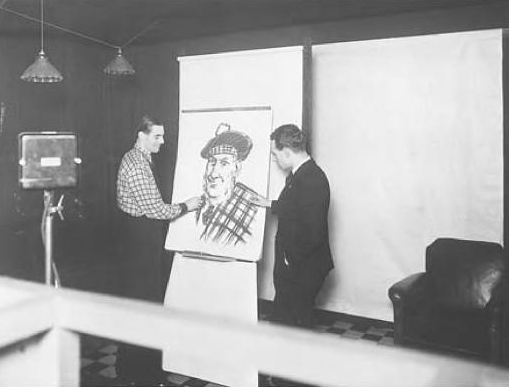

An early art show; a cartoonist draws live for the camera at Baird Studios, 1930

South of the River

In July 1933, Baird Television left Covent Garden and moved to Sydenham in deepest South London.

Here, at the Crystal Palace complex, a new studio was established, with the antenna attached to one of the glass palace’s towers.

Crystal Palace in 1934, one year after Baird Television moved in

John Logie Baird also made his own personal home in the area, on Crescent Wood Road, a short walk from the Crystal Palace studio.

John Logie Baird’s Sydenham House & Blue Plaque

However, the hard luck which had plagued John in his previous business ventures was about to come back and haunt him…

On 30th November 1936, the Crystal Palace burnt down, taking Baird Television studios with it.

Two weeks later, before the ashes had even cooled, the BBC- who were now really starting to get into the T.V thing- announced that they were scrapping Baird’s system in favour of more modern equipment which had been developed by Marconi-EMI.

The BBC moved their T.V wing to Alexandra Palace; the North London twin of the now vanished Crystal Palace.

Television continued to remain an ultra-expensive luxury and, on the 1st September 1939, following a Mickey Mouse cartoon, test card and a preview of up and coming programmes, the service suddenly went off air; closed down by the government in anticipation of the World War which was about to erupt; the fear being that enemy aircraft would use the television signals to hone in on their targets.

The first few years of television had come to an end, and the medium would not be seen again until 1946.

*

Despite the cruel setbacks, John Logie Baird’s appetite for invention remained as strong as ever.

The ingenious Scotsman went onto experiment with high definition colour, large-screen televisions, video recording devices and even made early ventures into infra-red. It is believed that, during WWII, Logie Baird carried out important work on the new radar network.

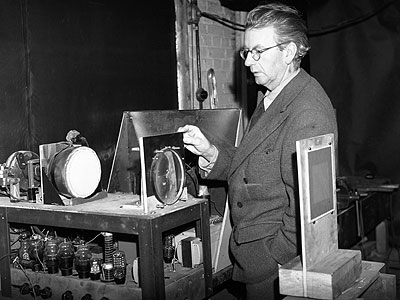

John Logie Baird hard at work in Sydenham

John Logie Baird died at the age of 57 on June 14th 1946.

This final clip, from 1937, shows the great innovator with the machine he forged in his Frith Street attic. Today, a working model of his revolutionary device can be still be viewed at the Science Museum in South Kensington.