WW1 100: London’s Memorials… The Machine Gun Corps & the Man Who Mended Faces

2014 will mark the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War One.

Raging from July 28th 1914 to 11th November 1918, this hellish conflict was the world’s first truly modern war, characterized by the widespread use of tanks, aircraft, heavy artillery and poison gas.

So intense was the fighting it is said that, during particularly heavy clashes, the thunder of guns could be heard echoing as far away as London.

Leaving Europe with deep physical and psychological scars, the Great War claimed a grand total of 16 million lives and left a further 21 million injured.

‘Gassed’ by John Singer Sargent, 1919. This painting is part of the Imperial War Museum’s collection.

On a personal level, my Great Great Grandfather- who was also named Robert- was shot at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

Although he was lucky enough to survive (had he not, I would not be sitting here writing this now), the bullet he took remained in his body for the rest of his life.

*

To mark this sombre landmark in our relatively recent history- and as my personal tribute to all of those who died, whatever their nationality- I have decided to start a new series which, over time, will take a look at London’s many World War One memorials and the stories behind them.

I shall begin with ‘The Machine Gun Corps’ memorial.

The Machine Gun Corps Memorial

Hyde Park Corner

When war first erupted in the summer of 1914, the British Military were still very much of a 19th century mind-set, confident that traditional infantry and cavalry based tactics would be sufficient enough force to seize victory… a tragically naïve assumption which was starkly portrayed in the 2011 film adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s book, ‘Warhorse’ (please click below to view):

After a few bloody months on the Western Front, it soon became clear in which direction the conflict was heading, leading to the formation of the Machine Gun Corps in October 1915.

During WWI, the Machine Gun Corps were deployed in a wide range of theaters including France, Belgium, Palestine, Egypt, East Africa and Italy.

Because of the nature of their weaponry, troops from the MGC often fought well beyond the front line; a factor which earned the Corps both a high casualty rate and a darkly comic nickname… ‘The Suicide Club’.

Seven members of the Machine Gun Corps were awarded the Victoria Cross; the highest possible accolade for bravery.

The Memorial

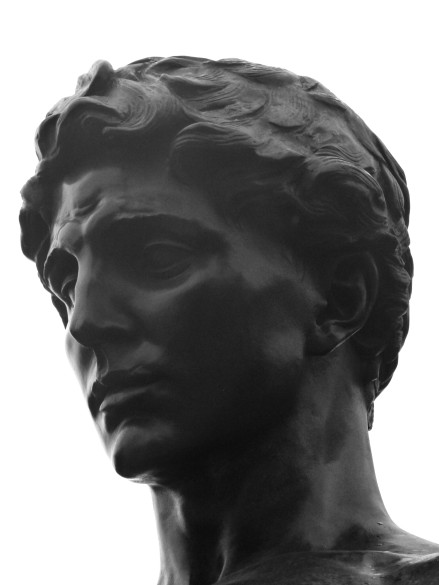

Unveiled in 1925, the memorial to the fallen of the Machine Gun Corps is embodied by a statue known as the ‘Boy David’; the Biblical figure who proved his worth after slaying the fearsome giant, Goliath.

Although we tend to associate David with heroism and triumph over adversity, his representation in this case is naked; something which suggests a sense of vulnerability.

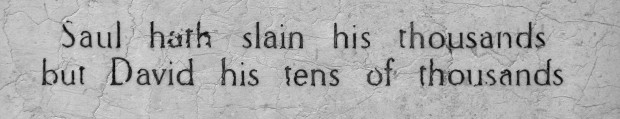

The statue’s plinth includes a quote from the Book of Samuel; “Saul hath slain his thousands but David his tens of thousands”; a grim nod to the impact which the Machine Gun Corps had on the course of the war.

On either side of the statue sit two ‘Vickers’ machine guns, each encircled with laurel wreaths. These fearsome weapons are actually real models… so it is some comfort that they are now encased in bronze.

The rear of the statue provides a brief history of the Corps:

“The Machine Gun Corps of which His Majesty King George V was Colonel in Chief, was formed by Royal Warrant dated the 14th day of October 1915.

The Corps served in France, Flanders, Russia, Italy, Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia, Salonica, India, Afghanistan and East Africa.

The last unit of the Corps to be disbanded was the Depot at Shorncliffe on the 15th day of July 1922.

The total number who served in the Corps was some 11,500 Officers and 159,000 other ranks of whom 1120 Officers and 12,671 other ranks killed and 2,881 Officers and 45,377 other ranks were wounded, missing or prisoners of war.”

*

When first erected, the memorial stood on Grosvenor Place; just south of Hyde Park Corner.

This first site was short-lived, with major road works soon requiring the statue’s removal. It was placed in storage for many years, finally returning in 1963 when it was placed at its present site on the northern side of Hyde Park Corner, backing onto one of London’s busiest road junctions.

An annual observance is held at the statue on the 2nd Saturday of every May.

Francis Derwent Wood

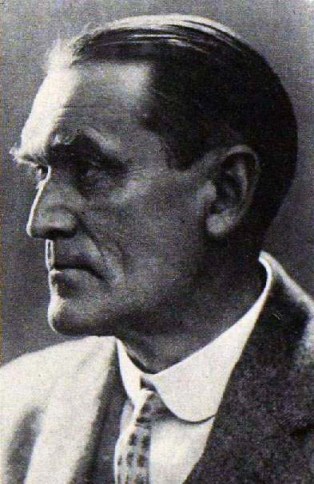

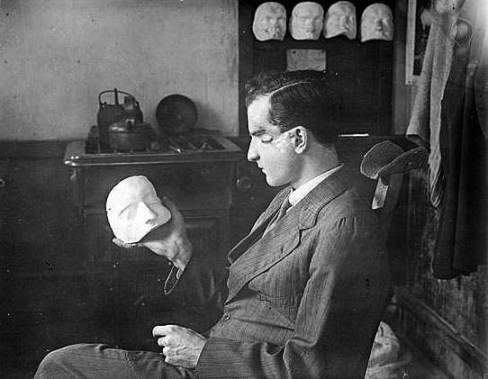

Perhaps the most poignant factor about the Machine Gun Corps memorial is the story behind its sculptor; Francis Derwent Wood.

Francis Derwent Wood was born in the Lake District in 1871 and went onto teach sculpture at the Glasgow School of Art.

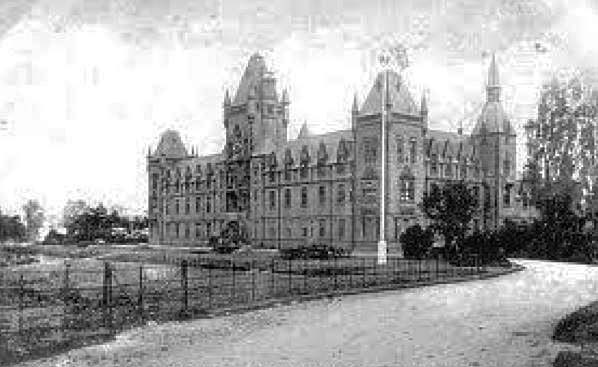

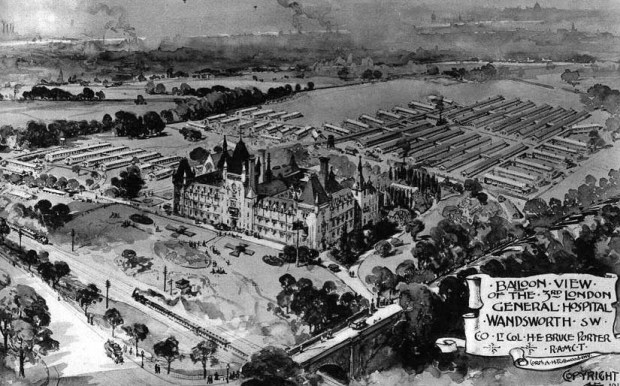

When war broke out in 1914, he was too old for military service, so volunteered to work in the bustling hospital wards, coming to be based at the 3rd London General Hospital in Wandsworth.

Originally built in the 1850s as a home and school for orphans, this grand building was requisitioned in WW1 for use as a military hospital.

To cope with the sheer number of wounded troops being brought it, a temporary platform and station were built on the hospital’s western side (which backs onto one of the main lines into Clapham Junction).

A field behind the hospital (which is today a cricket ground) became an overflow area, lined with row after row of marquees standing in as temporary wards.

Postcard displaying the 3rd London General Hospital, Wandsworth. The railway lines which delivered wounded troops can be seen to the south, the overflow tent-wards towards the north.

Today, the former hospital is now known as the ‘Royal Victoria Patriotic Building’; a complex of apartments, workshops, studios, a drama school and a restaurant called ‘Le Gothique’.

The former 3rd London General Hospital today… now known as the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building (image: Google).

*

At the 3rd London General Hospital, Francis Derwent Wood encountered many young men who had suffered horrific injuries inflicted by the terrifying new weaponry.

Facial traumas were especially commonplace; if a squaddie quickly popped his head over the trench, an unexpected explosion or burst of enemy fire could have catastrophic results.

In one account, an American soldier, shot in the skull in 1918, described the experience; “It sounded to me like someone had dropped a glass bottle into a porcelain bathtub… a barrel of whitewash tipped over and it seemed that everything in the world turned white.”

In some cases, victims literally lost half their face… yet somehow managed to survive.

Although plastic surgery techniques were being pioneered at the time, there were some unfortunate souls who even this could not help.

Exposed to such tragedies, Francis Derwent Wood had a brain-wave.

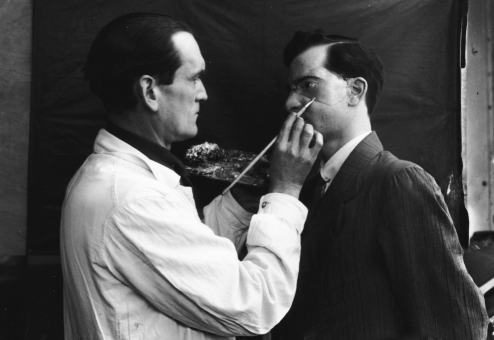

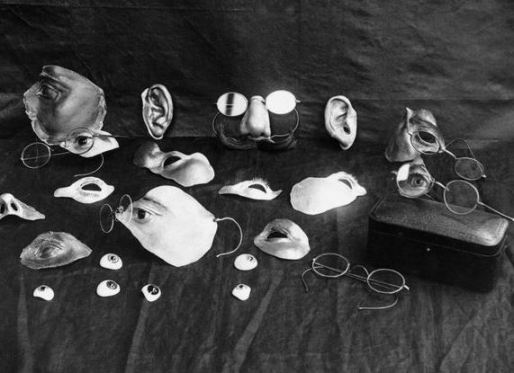

Realising that his artistic skills may be able to help those with extensive facial scars, he took it upon himself to set up the ‘Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department’ within the hospital where, beginning in March 1916, he began to use his expertise to create custom masks for his patient’s shattered faces.

Taking up to a month to create, each mask, which was made from ultra-lightweight metal and painted in enamel to match the wearer’s skin tone, was a work of art in itself, designed to fully disguise the affected area.

Where eyebrows and moustaches were required, slivers of tinfoil were used- rather like the technique used on ancient Greek statues.

Patients at the hospital quickly gave the department an affectionate nickname; ‘The Tin Nose Shop.’

This creative solution did wonders for the morale of young men faced with a future of horrified stares and social exclusion- in Sidcup for example, which was also home to a facial hospital, certain park benches were designated for the use of patients…and were painted blue as a warning to passers-by of a more sensitive nature.

Interviewed in The Lancet in 1917, Francis said; “My work begins where the work of the surgeon is complete…The patient acquires his old self-respect, self-assurance, self-reliance… takes once more to a pride in his personal appearance. His presence is no longer a source of melancholy to himself nor the sadness of his relatives and friends.”

Derwent Wood’s work was soon noticed by the American sculptor, Anna Coleman.

After liaising with Derwent Wood and with support from the American Red Cross, Anna opened her own mask studio in Paris, where she continued the pioneering work on severely wounded French and American troops.

A video of this studio survives, which gives a good idea of the process involved at the hospitals in Paris and London (please click below to view):

Unsurprisingly, Anna Coleman and Francis Derwent Wood received many grateful letters from those they’d helped.

One particular response is heart-breaking in what it says;

“Thanks to you, I will have a home… the woman I love no longer finds me repulsive.”

*

Francis Derwent Wood’s studio was wound down in 1919.

Although he was able to help several hundred men, this was a mere drop in a very sad ocean- over 20,000 would return from the continent with facial wounds.

After the war, Francis was commissioned to create memorials in honour of the men who never returned. These works include a statue for Liverpool’s Cotton Association, ‘Humanity Overcoming War’ in Bradford and work on the memorial plinth in his home town of Keswick.

He also created a controversial sculpture of a crucified soldier; ‘Canada’s Golgotha’ which can be seen in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa.

London’s Machine Gun Corps memorial was one of Derwent Wood’s last pieces. He died just two years after its unveiling.

In 1929, a small, bronze copy of the Boy David was made by Edward Bainbridge Copnall as a memorial to Francis Derwent Wood.

Bequeathed by the Chelsea Arts Club, it can today be seen on the north side of Chelsea Embankment, overlooking Albert Bridge.