Suburban SOS… An Early Aviation Diaster

Despite a natural fear harboured by many, it’s a well-known and often quoted fact that flying is one of the safest forms of travel.

Ever year, millions of jet-setters are whisked around the globe, their lives securely entrusted to the hands of highly trained professionals and an array of multi-million pound technology.

On the ultra-rare occasions in which air accidents do happen, the very nature of such incidents often result in a tragedy of catastrophic proportions.

Over the years, scores of notorious aviation disasters have occurred all across the world.

However, the very first chartered plane crash in which civilian passengers perished took place very close to home… in the leafy, north London suburb of Golders Green…

*

Before examining this tragic aviation first, we should take a quick look at the airport which the flight in question originated from… Cricklewood Aerodrome.

Now long-vanished, Cricklewood Aerodrome owed its existence to a large aircraft factory known as Handley Page.

The factory itself had been established at its north London site in 1912 by Frederick Handley Page who, just 12 years after the pioneering achievements carried out by America’s Wright Brothers, saw a market for the newfangled flying contraptions.

Once an aircraft left the Handley Page production line, it was flown directly to the purchaser. To facilitate this service therefore, the company laid out an airfield next to the factory.

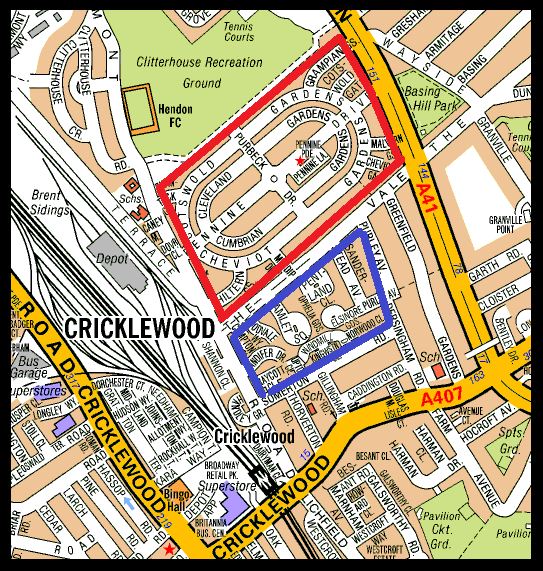

Map indicating the layout of the former Handley Page complex. The location of the factory buildings is marked in blue, the adjoining airfield in red. This area lies a short distance south of Brent Cross shopping centre. (A-Z imaging)

In 1914, just two years after the factory had opened, WWI; the Great War erupted… the very first conflict to involve aerial combat.

As a consequence, the Handley Page factory at Cricklewood turned itself over to the war effort, churning out heavy bombers which, at the time, were the largest winged aircraft ever created, their bulky size capable of stashing away some 2,000lbs of explosives.

In the following dramatic clip, taken from the 2008 film, The Red Baron, the fearsome German flying ace, Manfred von Richthofen can be seen annihilating an unfortunate Handley Page bomber…

Once the Great War was over and normalcy began to return to Europe, the Cricklewood-based manufacturer restored their facilities to more peaceful purposes.

In 1919, the group established Handley Page Transport, converting their former bombers into passenger planes whose range made them capable of serving pioneering passenger routes between London and Paris.

For over a year, the adolescent airline transported the brave and well-to-do between the two capitals without incident… that was until the 14h December 1920.

Just before midday, the regular scheduled flight to Paris took off from Cricklewood Aerodrome. The model of aircraft serving the route was a Handley Page O/400, its droning twin propellers lifting the heavy plane into the misty sky.

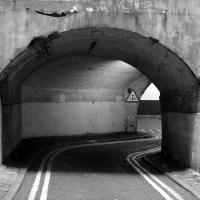

A Handley Page passenger plane at Cricklewood Aerodrome being prepared for a commuter flight to Paris, February 1920.

Moments after rising into the murky air, the vintage passenger plane encountered difficulties… for reasons unknown, the airliner was unable to climb and dropped so low that it brushed the branches of a large oak tree; a collision which no doubt did little to relieve its technical woes.

Seconds later, the aircraft plunged into the back garden of number six, Basing Hill, a quiet, residential street on the western outskirts of Golders Green.

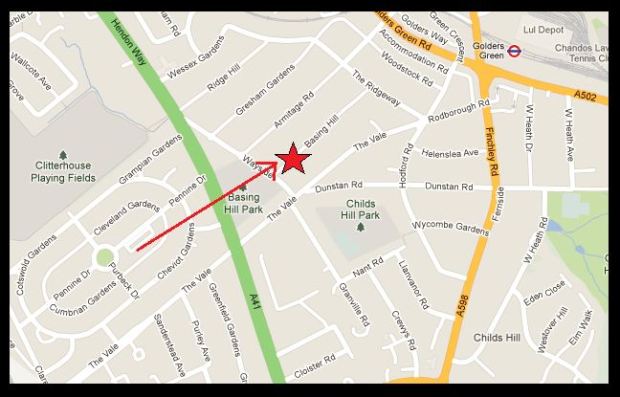

Map indicating Basing Hill and the approximate, disastrous path taken by the struggling aircraft. (Google imaging).

As the Dundee Courier reported at the time, “Within half a minute the whole machine- which was nearly eighty feet long- was burning fiercely. The flames rose to an enormous height.”

The crash must have come as quite a shock for the occupants of number 6 Basing Hill- an elderly pensioner called Mrs Robinson and her one servant…

As well as bursting into flames, the downed craft also forged a huge hole in the garden… and was reported to have demolished “a short wooden fence and scullery.”

Despite the seemingly quaint nature of this crash, the incident was certainly no picnic for the unfortunate souls trapped inside the flying machine.

Although four passengers managed to clamber out of the doomed plane shortly after impact, two of the crew and two passengers were still trapped inside… as the newspaper report continued; “Their agonised cries for help came from within the circle of flame and continued for several minutes…”

December 15th 1920 headline from the Dundee Courier, describing the Golders Green crash in gruesome detail…

Although locals rushed to the scene to help, the intensity of the flames beat back any hope of rescue.

Once the raging fire had been extinguished, the deceased victims were recovered. “Charred beyond recognition”, they received little dignity; dumped on the back of a lorry and carted off to the local coroners court for a post mortem.

The names of those who perished were Mr R. Bager- the pilot, Mr J.H Williams- the mechanic… and the two trapped passengers; Mr Salinger (from Boxmoor, Hertfordshire) and Mr Vander (from Paris)- the unfortunate Englishman and Frenchman sadly gaining their place in the history books as the first two civilians to lose their lives in a chartered airline crash.

*

Cricklewood aerodrome ceased operation in 1929, moving to a new base in Radlett, Hertfordshire.

In 1924, Handley Page Transport merged with two other companies, forming Imperial Airways… the forerunner to what we now know as British Airways.

Although Cricklewood airfield quickly disappeared beneath a housing estate (centred around Pennine Drive), the neighbouring Handley Page factory remained in business right up until 1964.

However, just like the neighbouring airfield, that site too has now been built over … the only building to remain from the once vast complex is an old office block, visible at the western end of ‘The Vale’…

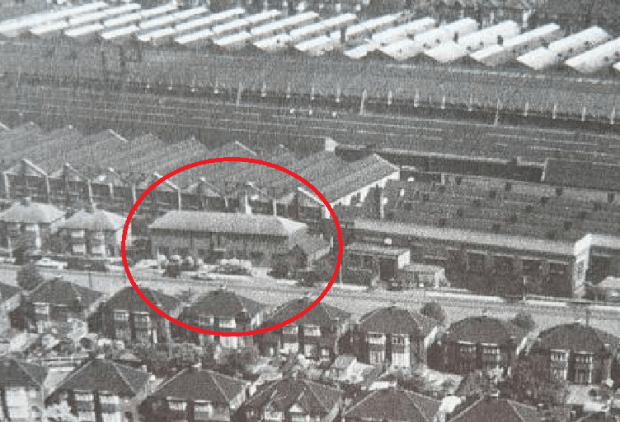

Aerial view of the Handley Page factory, Cricklewood. The one surviving building (pictured in the image above) is circled in red.

To read about two more of London’s grim transport firsts (this time related to the motor-car), please click here.

Disturbing Daubs: Francis Bacon’s London

With the evenings growing darker and Halloween in the air, I think now would be a suitably atmospheric time to take a look at the London of Francis Bacon; one of the 20th century’s most celebrated artists, whose dazzlingly eccentric brain gave life to many disturbing, gruesome… and, in some cases, downright petrifying images…

Francis Bacon was born on Lower Baggot Street in Dublin, Ireland on 28th October 1909.

Emotionally, his childhood was a fraught one, the young Francis often finding himself locked in a cupboard whenever his natural inquisitiveness became too bothersome for his mother.

Unsurprisingly, being confined in the claustrophobic darkness would induce terrified bouts of screaming. As an adult, Bacon is once said to have remarked; “that cupboard was the making of me…”

At the tender age of 16, Francis left home and embarked upon a number of adventures across Europe, starting with London where he arrived in the autumn of 1926.

During his first encounter with the capital, Francis secured work in a women’s clothes shop on Poland Street in Soho.

However, his young and carefree attitude didn’t sit with such a conventional business and, after insulting the store’s owner, he was promptly sacked.

Bacon then tried his luck in Berlin which, in those days before the spectre of Nazism erupted, was a liberal hotbed of art, literature and creative thought.

He then ventured onto Paris, where he was especially taken with French culture, quickly discovering a passion for good food, wine and the latest trends in art.

*

In 1928, Bacon returned to London where he soon established himself as an interior designer.

His new business was based was in a tiny flat on Queensbury Mews West in South Kensington… a location he perhaps picked thanks to the small French community which continues to flourish around the area to this day.

Bacon left the mews in 1931 and spent several years drifting in and out of accommodation around Chelsea, Fulham and Hampshire.

*

Upon the outbreak of war in 1939, he presented himself for military service but was rejected on medical grounds due to his asthma.

Following this refusal, Francis volunteered as an air-raid warden; a role which would have brought him into regular contact with the carnage wrought by the nightly shower of bombs, the dust from rubble only serving to make his breathing even more troubled.

There can be little doubt that bearing witness to the bodies of civilians torn and mutilated by the horror of modern warfare would later have a profound impact on Bacon’s artistic vision…

Devastation, 1941: An East End Street. This painting was created by Graham Sutherland, a friend of Francis Bacon.

*

In 1943, Francis Bacon moved to new digs in the ground-floor flat of 7 Cromwell Place, a stone’s throw from the Natural History Museum.

At the time, the building was rather draughty having suffered considerable bomb damage. This didn’t bother Francis though; he was more concerned in blacking out the windows… not as an air-raid precaution, but as cover for an illegal gambling den he’d set up!

Throughout his life, having a high-stakes flutter proved to be one of Bacon’s true vices.

It was a mind-set which also influenced his work. Having received no formal art-training, he frequently viewed the practice of trying out risky new techniques as a gamble… when it didn’t pay off, the offending canvas would be slashed and destroyed.

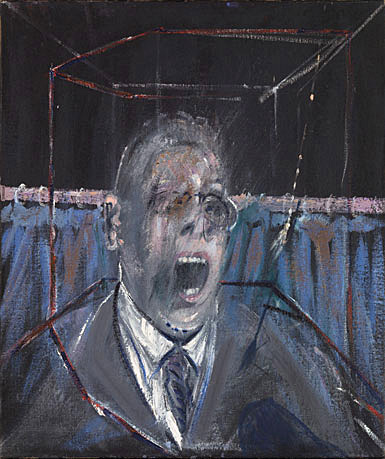

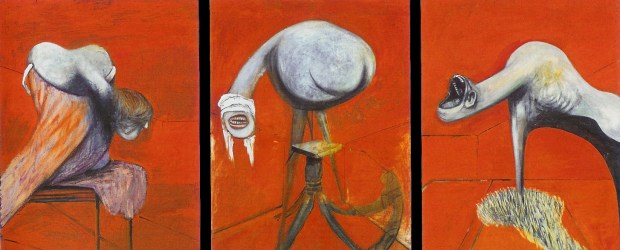

Betting aside, it was at Cromwell Place that Francis Bacon’s career as an artist really took off when, in 1944, he set about painting Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion….

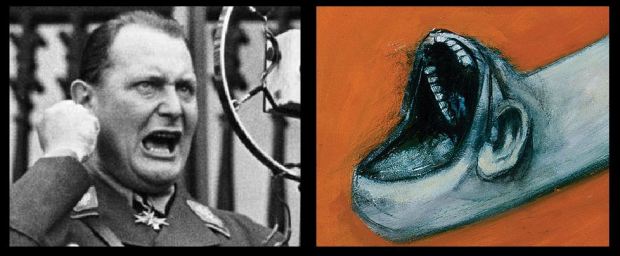

This ‘triptych’ of grotesque creatures, which could be seen as representing the torment of war, the baying mouths reminiscent of the fascist dictators who’d plunged Europe into darkness, were first displayed at the Lefevre Gallery in 1945 on Mayfair’s Bruton Street.

After thoroughly unsettling the public, the trio of disturbing images were acquired by the Tate Gallery in 1953.

The next startling piece to emerge from the Cromwell Place studio was another surreal work simply entitled, Painting which was unveiled in 1946.

Painting was displayed at the Redfern Gallery on Cork Street and was promptly purchased by a dealer for £200; approximately £6,700 in today’s money.

Once the art-world had discovered Francis Bacon there was no stopping him, and for the next 47 years he provided galleries with a regular stream of challenging and deeply unnerving works.

Study after Velzaquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1954… one of Bacon’s most iconic and terrifying visions…

In 1961, Francis Bacon moved to a new studio on Reece Mews, moments away from South Kensington junction and his former premises on Cromwell Place.

Converted from a former horse stable, Bacon would maintain the studio for the rest of his life.

Despite his wealth and fame, the Reece Mews property remained starkly simple.

The artist occupied only the upper level, which was reached via a dangerously narrow staircase (presumably, his large canvases were hoisted through the upper balcony door).

The toilet was squeezed out on the landing, as was the kitchen… which also contained a bath! During the colder months, Francis would light the cooker’s gas hob and use it to heat the room up whenever he took a dip!

Francis Bacon’s studio was notoriously messy and the artist himself can be seen describing the chaotic environment in the following clip from a 1985 episode of The South Bank Show:

Essentially, the South Kensington studio was for working and sleeping in only.

When he wasn’t painting, Francis Bacon could be found out and about in London’s West End, a regular face and much loved character amongst the bohemian bars and restaurants of Soho.

A candid shot of Francis Bacon drinking in Soho’s ‘French House’, December 14th 1984. (Image: Neil Libbert, via ‘The Guardian’)

It was in the West End that Francis Bacon splashed around much of his fortune; gambling heavily and showing great generosity towards friends when it came to paying the bill for many a large meal; especially at his favourite restaurant, Wheelers on Mayfair’s St James’s Street.

In 1948, Francis Bacon became one of the founding members of The Colony Room on Dean Street; a Soho institution and legendary hang out for the unorthodox which sadly closed in 2008.

Francis Bacon at the Colony Room, Dean Street with Muriel Belcher; the club’s original owner. Francis painted Muriel on a number of occasions. (Image from alexalienart)

*

On 28th April 1992, whilst visiting a friend in Madrid, Francis Bacon suffered a heart attack, and passed away at the age of 82.

His famously scruffy studio, in which he still had a number of works in process, lay undisturbed for a number of years…. That was until 1998, when the Hugh Lane gallery in Dublin decided that the workshop of one of the city’s most famous sons deserved preserving.

For three years, a team from the gallery carefully catalogued and noted the position of every single item in the haphazard South Kensington studio; thousands of books, photographs and other materials.

The items were then carefully packed away and taken to the Dublin gallery where they were painstakingly reassembled into their original layout. Even the paint-splattered walls were transported to the Irish capital.

Francis Bacon’s studio, encapsulated as it appeared in 1992 and now transplanted to Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery (image: Conde Nast Traveller)

The result is an extraordinary, protected time capsule which is now a popular tourist attraction. To find out more about the relocated space, please click here.

*

To this day, Francis Bacon’s paintings, with their mysterious distortions and numerous, tormented jaws locked in perpetual, frozen screams, remain intriguing and unsettling.

However, when once asked what he thought of people regarding his work as visions of horror, Francis’ reply was rather sobering:

“What horror could I make that could compete with what goes on every single day? If you read the newspapers, if you look at television, if you know what’s going on in the world… what could I do that competes with the horrors going on?”…

304 Holloway Road: Inside the Tortured Mind of the ‘Telstar Man’

At 304 Holloway Road you’ll find a 24 hour grocery store, above which sits a shabby three-storey flat, complete with decaying paintwork and a boarded up window.

304 Holloway Road

Despite its dilapidated state, the apartment on this north London road actually has quite a tale to tell… a story involving music, madness and murder.

*

Between 1961 and 1967, the accommodation above 304 Holloway Road was rented out by a fellow named Joe Meek.

Joe Meek (photo: Getty Images)

Born in Newent in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean in 1929, Joe Meek’s early upbringing was rather bizarre- for the first four years of his life he was raised as a girl thanks to his mother’s intense desire to have a daughter.

Joe Meek first arrived in London in 1954 after landing a job as a sound engineer for Stones; a popular radio and record shop on the Edgware Road.

It was a job which suited him well. From an early Joe had been fascinated with electronics and was always scavenging components with which he could tinker. With these various bits and bobs he would experiment, cobbling together circuits, radios and so on.

Joe Meek was also fascinated by outer space; a passion which was nurtured when he became a radar mechanic for the RAF during his period of national service.

Joe Meek whilst serving in the RAF

After spending time working at Stones, Joe progressed to a new job, becoming a producer at Lansdowne Recording Studios, moments away from his home on Arundel Gardens in Notting Hill.

Confident in his new role, he wrote a letter home to his mother stating, “I’m sure your son is going to be famous one day, Mum.”

Lansdowne Recording Studios (photo: Google Street View)

At Lansdowne, Joe Meek proved to be quite the maverick, frequently ignoring his superiors in order to pursue his quest of developing new sound techniques.

Whilst at the Notting Hill studio, he maintained a strictly guarded ‘secret box of sounds’; a container kept under lock and key which held all manner of unusual objects for creating unorthodox audio effects.

Before long, Joe became tired of working within a large organisation and decided to go it alone as an independent record producer.

In pursuit of his ambition, he moved into 304 Holloway Road where he set about creating a makeshift but innovative studio.

304 Holloway Road (marked in red) as it appeared in the early 1960s (copyright Jim Blake)

The independent label established in Holloway became known as RGM Records (Joe’s full birth name actually being Robert George Meek).

At the time, such a move was revolutionary.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, pop records were the domain of big corporations, tightly controlled by cigar-puffing businessmen. The sound engineers who worked for these companies did so in strict, clinical environments, armed with clipboards and donned in white lab coats.

Sound engineering in the traditional way

Joe Meek’s way of working was the complete opposite to this traditional method.

Packed with all manner of improvised equipment, his Holloway Road studio was easy-going and unconventional.

From the stairway to the bathroom, all rooms were made available for recording sessions. Joe would also use seemingly every day domestic items to create all manner of new sounds, the flat itself more or less becoming an instrument in its own right. He was particularly fond of stamping on the upper floors to enhance drumming effects.

As his experiments developed, Joe Meek’s work took on an eerie, futuristic sound; one which he hoped would define an era as the space-age began to grip the 1960s.

Joe Meek at work in his Holloway Road studio

*

The first major hit to be produced at 304 Holloway Road was Johnny Remember Me, a song about a young man haunted by his dead lover. Sung by John Leyton, the single reached UK number one in July 1961.

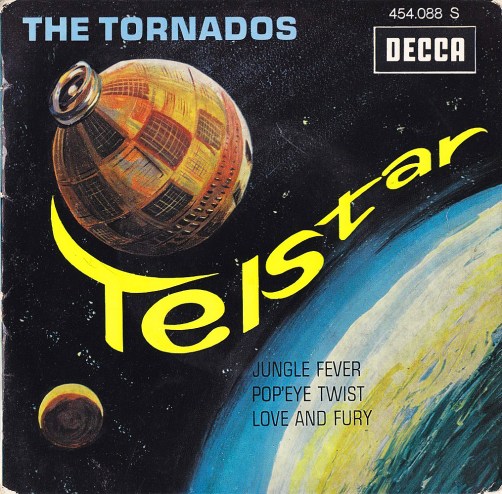

The success of Johnny Remember Me was followed by an even bigger hit in August 1962… Telstar.

Written and recorded by Joe Meek at 304 Holloway Road, Telstar was an instrumental track created to celebrate the success of the radical new communications satellite which had been launched in July 1962.

The original Telstar satellite under construction

Played by Meek’s backing group, The Tornados, the ode to space technology featured all manner of sci-fi sounds which had been concocted in the unlikely setting of the north London studio.

The record was an instant success. As well scoring a number one in the UK, it became the first single by a British group to hit number one in the United States; a massive achievement.

Telstar is now considered to be Joe Meek’s masterpiece (it can be heard at the end of this article) and such was its popularity that it should have set him up financially for life.

However, a French composer by the name of Jean Ledrut claimed that Meek had pinched the tune from a score he’d written for the Napoleonic film, Austerlitz. This led to a lengthy legal battle which prevented Joe Meek and the Tornados receiving any royalties from their hit.

*

Joe Meek continued to forge extraordinary new sounds in his cramped studio, but the stresses of life and business were beginning to take their toll.

Joe Meek in 1966; photo copyright David Peters (David managed a group called ‘Dannys Passion’ who recorded with Joe Meek. You can read about his memories here: http://www.dannyspassion.webeden.co.uk/)

Joe was homosexual- illegal in Britain at the time and something which led to the producer being blackmailed on numerous occasions.

By the mid-1960s, the music scene was changing rapidly and Joe Meek’s once innovative melodies were beginning to lose favour. The last major hit to be produced at Holloway Road was Have I the Right by The Honeycombs (a band noted for having a female drummer) which was released in 1965.

As the decade pushed on, RGM records began to struggle financially. Convinced he’d win the Telstar case, Joe had been spending heavily, confident that the money would eventually come through. It didn’t though of course.

Friends of Joe Meek noticed a distinct change in his character.

Clearly under stress, he’d developed a short, volatile temper and, more worryingly, had become intensely paranoid, convinced that his Holloway Road flat had been bugged by rival companies in order to steal his ideas.

So paranoid was Joe that he refused to leave anyone alone in the studio for fear that they’d snoop on his work.

Joe Meek outside his Holloway Road studio

He was also becoming deeply obsessed with the occult and took to setting up recording equipment in graveyards, hoping that spirits from the other side would offer him guidance.

One evening, one of these graveyard recorders picked up the sound of a cat mewing- Meek was convinced that a human spirit was trapped in the feline body and that the cat-like noises were in fact desperate calls for help.

He even began to claim that his idol, Buddy Holly (killed in a plane crash in 1959) made frequent visitations to the Holloway Road flat late at night, offering snippets of musical wisdom.

The legendary Buddy Holly… whom Joe Meek claimed would regularly visit 304 Holloway in spirit form…

*

Joe’s mental state was deteriorating rapidly.

in January 1967 things came to a head when the body of a 17 year old youth named Bernard Oliver was discovered in rural Suffolk. The victim had been murdered in a particularly gruesome manner; expertly cut into eight pieces before being packed into a suitcase.

Bernard Oliver had been working as a factory hand in North London and, prior to his murder, had been missing for two weeks.

When the Metropolitan police stated that they would be interviewing all known gay men in London, Joe Meek became terrified. Even though he had absolutely nothing to do with the case, his delusions were pushed to new heights as he became convinced that the police would somehow find a way of implicating him.

*

On the morning of 3rd February 1967 (which happened to be the 8th anniversary of Buddy Holly’s tragic death), Patrick Pink who was a friend and studio assistant, called in to see Joe- who refused to speak and promptly stormed off upstairs.

Patrick mentioned the fact that Joe was in a bad mood to Violet Shenton, the long suffering landlady of 304 Holloway Road who often took to knocking the ceiling with a broom handle when the sound levels became too much.

Violet Shenton

In her typically blunt, but motherly and well-meaning manner, Mrs Shenton stubbed out a cigarette and told Patrick that she’d go and sort her tenant out. When she arrived upstairs, the last words Violet was heard to say were “calm down Joe”… a statement which was suddenly followed by two gunshots…

Using a hunting gun which had been left in the flat by singer, Heinz Burt, Joe Meek had committed both murder and suicide within seconds, shooting Violet before quickly turning the weapon on himself.

He was 37 years old.

*

Just three weeks after the lethal shooting, a French court finally brought the Telstar case to a close.

They ruled in Meek’s favour, stating that he couldn’t possibly have plagiarised Jean Ledrut’s work as the film wasn’t released in the UK until 1965; three years after the success of Telstar.

Today, Joe Meek’s former home and studio sits quietly on the Holloway Road, offering little sign as to the creativity and tragedy which played out within decades before.

304 Holloway Road… a shadow of its former self

The only reminder of the premises’ former role is a black plaque… which, quite fittingly, is located right beside a derelict satellite dish; an item which Joe Meek would no doubt have taken great interest in.

A few hundred yards away, another small reference can be found… a Banksy-esque graffiti mural depicting Joe Meek on a grubby wall opposite Holloway Road tube station.

To listen to Joe Meek’s most famous work, click the clip below: