The Gunpowder Plot

November 5th as we all know marks Bonfire Night; a chilly festival of sparklers and fireworks commemorating the moment when a conspiracy to blow up Parliament was foiled at the last minute.

But how exactly did the Gunpowder Plot come about?

The plot’s roots originated during the reign of Elizabeth I; a time when persecution of Catholics had steadily risen, with fines, imprisonment and execution meted out to those who practiced the faith.

Queen Elizabeth I (image: BBC)

When King James I came to the throne in 1603, Catholics were hopeful he’d be more sympathetic- after all, his mother, Mary Queen of Scots had herself been Catholic. This optimism vanished however as James continued to enforce Elizabeth’s policies and banished all priests from the country.

King James I (portrait by John de Critz)

Infuriated by these events was Robert Catesby, a 32 year old Catholic who’d sheltered priests at his home in Uxbridge since the 1590s. In February 1604, he met with two similarly disillusioned young men- Thomas Wintour and John Wright- at another property he owned in Lambeth. It was here that Catesby first proposed the idea of assassinating the king with explosives.

Robert Catesby’s home in Lambeth

Agreeing to the plan, Wintour travelled to Europe to seek support. In Flanders he met and recruited 34 year old Yorkshireman, Guy Fawkes (aka ‘Guido’); an explosives expert and mercenary fighting for the Spanish army.

Guy Fawkes, illustrated by George Cruikshank

In May 1604, Guy Fawkes came to London and met the plot’s ringleaders at the Duck and Drake inn on The Strand where an oath of secrecy was sworn. In all, there would be 13 collaborators.

An early illustration depicting a number of the Gunpowder Plotters

Later that year, another of the group- Thomas Percy- blagged a job as a royal bodyguard and acquired a house close to the House or Lords from which the conspirators began digging a tunnel. Guy Fawkes, under the rather unimaginative alias, ‘John Johnson’, posed as Percy’s servant, meaning he was at liberty to wander around Parliament.

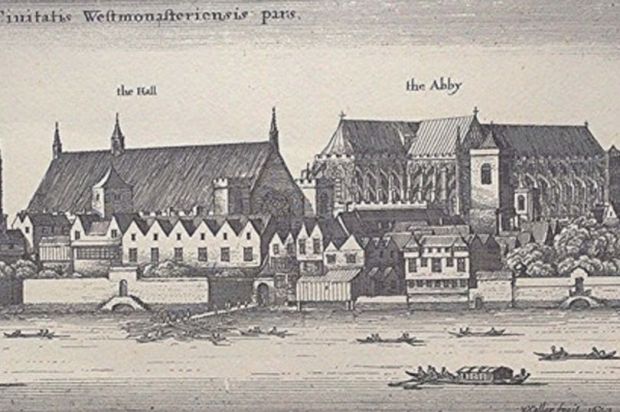

Parliament in the 1600s

In March 1605, a golden opportunity arose when a vault directly beneath the House of Lords became available to rent.

The laborious tunnelling was abandoned and Guy Fawkes began transferring the gunpowder (which had been stashed across the river in Catesby’s home) directly into the cellar. There was no need to rush. Due to an outbreak of plague, the opening of Parliament- at which King James would be in attendance- had been delayed until November 5th 1605.

The plot began to unravel in late October when Lord Monteagle, whilst dining in Hoxton, received an anonymous letter- most probably from his brother-in-law, Francis Tresham who was one of the plotters- warning him to avoid Parliament’s opening due to the threat of a “terrible blowe.”

19th century illustration of Francis Tresham

With suspicions raised, Monteagle passed the letter to the king who ordered Parliament to be searched.

Lord Monteagle

On the morning of November 4th, Guy Fawkes was spotted and questioned, but dismissed when he claimed he was merely a servant going about his business.

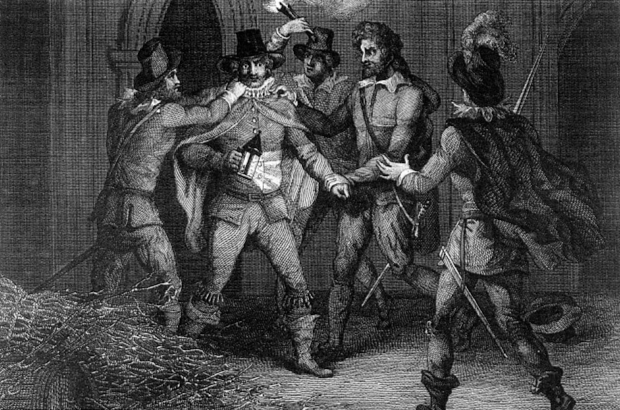

Still sceptical however, guards returned to Parliament in the early hours of November 5th where, once again, they discovered Guy Fawkes- this time equipped with a lantern, matches and fuses, and also dressed in a cloak and riding spurs for a hasty getaway. The plot has been rumbled.

The capture of Guy Fawkes

After his arrest, Guy Fawkes was hauled to the Tower of London where he was subjected to horrendous torture.

The Tower of London, 1600s

It took him three days to crack and name his fellow conspirators who’d fled along Watling Street (now the A5) towards the midlands.

Guy Fawkes’ signature…before and after torture

Armed with this information, the king’s men swiftly hunted them down. Catesby and Percy died in a shootout in Staffordshire, after which their heads were jabbed upon spikes outside Parliament.

Eight of the surviving plotters were found guilty of treason and consequently sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered.

The first four executions took place outside St Paul’s Cathedral on the 30th January 1606 and the second batch- including that of Guy Fawkes- were held the following day in Old Palace Yard, between Parliament and Westminster Abbey.

Old Palace Yard

After taking the noose Guy Fawkes suddenly leapt from the scaffold, snapping his neck for an instant death; thus sparing himself the horror of being disembowelled whilst still alive. His head was later drenched in tar and displayed on a spike above the gateway to London Bridge.

Francis Tresham meanwhile died from poisoning whilst imprisoned- a small mercy for the warning he’d supposedly given…

*

Halloween Special: Scary London Scenes (Part One)

Warning, this post contains clips which some readers may find disturbing.

Over the years there have been many eerie, unsettling and downright scary film and television sequences shot in London. Here is a small selection- complete with clips- to get you in the mood for Halloween…

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954)

Television was still in its infancy when this adaptation of George Orwell’s totalitarian novel was shown. Staring Peter Cushing, the play was acted and broadcast live from BBC’s Alexandra Palace on the night of the 16th December 1954.

At the time, this adaptation was the most expensive television drama to date- and also the most controversial, with the film’s subversive and disturbing tone leading to questions being raised in the Houses of Parliament.

The following clip is taken from the film’s climax in which Winston Smith is hauled to the petrifying ‘Room 101’ and threatened with a ghastly form of rat torture. In real life Peter Cushing really did have a phobia of rodents which makes his turn all the more disturbing.

*

The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961)

In The Day the Earth Caught Fire, nuclear bomb tests conducted by the USA and USSR have caused a catastrophic shift in the Earth’s orbit, pushing it on a deadly path towards the sun.

The story focuses on Peter Stenning, a journalist from the Daily Express who covers the crisis from his Fleet Street office. Although made in black and white, the final section of the film is tinted yellow to emulate Earth’s soaring temperatures. So intense is the heat that the Thames completely dries up.

As society collapses and the planet faces destruction, scientists detonate more nuclear bombs in Siberia in the desperate hope that the earth will be pushed back on course. In the final, eerie moments, the camera focuses on an almost deserted Fleet Street print room where two alternative headlines have been prepared: ‘World Saved’ and ‘World Doomed.’ The audience are left guessing as to which story goes to press…

*

Dr Who: The Invasion (1968)

Despite the obvious budget limitations, I’ve always found the Cybermen from the 1960s to be particularly chilling with their soulless eyes and uncanny electronic voices.

In this clip an army of Cybermen emerge from London’s sewers and begin their march on the capital, including an iconic shot of them stomping before St Paul’s Cathedral.

*

Death Line (1972)

Death Line (known as ‘Raw Meat’ in the USA) is a rather daft film in which a pack of cannibals lurk on the London Underground, snacking on hapless commuters. Much of it was filmed at the now disused Aldwych station (a site still popular with film and television crews today).

The original American trailer for the film can be viewed below.

*

The Omen (1976)

This modern classic about ‘Damien’- the young incarnation of the devil himself- was shot on location across London, including scenes at Lambeth, Hampstead Heath and Grosvenor Square.

In the film, Catholic priest, Father Brennan (played by Patrick Troughton) is aware of Damien’s true identity and attempts to warn Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck) who is the US ambassador to Britain and Damien’s adoptive father. The shocking scene in which Father Brennan meets his grisly fate was filmed beside the Thames in Bishop’s Park, Fulham (look out for Putney Bridge which can be spotted in the background).

Later in the film, Damien deliberately knocks his mother, Katherine (Lee Remick) off of a balcony, landing her in hospital. Unfortunately Katherine is still not safe and ends up being hurled from a hospital window by Damien’s psychotic nanny and protector, Mrs Baylock (Billie Whitelaw). This scene was filmed at Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow (which also happens to be where I was born!)

The Omen’s final scene in which Damien gives the camera a sinister (and unscripted) smile was shot just outside the capital at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey. For many years, Brookwood was linked to Waterloo station by a special funeral train (click here to learn more).

*

An American Werewolf in London (1981)

Like The Omen, this cult favourite features many London locations.

After a vicious werewolf attack on the Yorkshire Dales which leaves his friend dead, American backpacker, David Kessler (played by David Naughton) ends up in a London hospital where he falls for nurse, Alex Price (Jenny Agutter). As David has nowhere to stay, Alex invites him to her flat at Redcliffe Square, Earls Court (sadly, I’m not quite sure how a nurse would be able to afford to live here nowadays).

It is here, as a full moon looms, that David succumbs to his werewolf bite…and transforms into a beast in a celebrated, but highly disturbing special effects sequence made long before the days of CGI. Shortly afterwards, we see David’s werewolf form commit its first attack on a young couple outside The Pryors, East Heath Road, Hampstead.

The werewolf then goes onto pursue a hapless late-night commuter at Tottenham Court Road tube station.

Finally, in the film’s famous climatic scene, the werewolf goes on a shocking, bloody rampage across Piccadilly Circus before meeting its fate at the hands of police marksmen on Clink Street, Southwark.