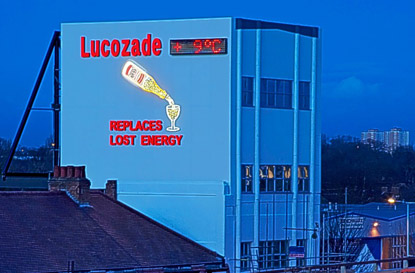

Cabbie’s Curios: Neon Lucozade

Earlier this evening, I was lucky enough to secure a fare to Heathrow Airport; a trip which always provides a welcome contribution towards the daily diesel fund.

Conveying a passenger to Heathrow during the rush hour is always guaranteed to get the adrenalin going… a battle through the London traffic, ploughing through a sea of glowing red brake-lights as the passenger anxiously examines their watch, wondering if they will ever make it into the darkening, twilight sky.

As you approach the western limits, the cabbie has to contend with the motorist’s arch-nemesis; the Hammersmith Flyover; a real head-ache maker which is currently reduced to one lane, swarming with traffic cones and gangs of workmen, all decked out in luminous orange.

Once over that, it’s the M4 motorway all the way; a final last sprint towards the vast airport; clock ticking away, darting between lorries bound for Heathrow’s cargo terminal whilst, to your left, large aircraft from all over the globe lumber into London on their final approach- looking slow and cumbersome, but always managing to overtake you.

Once at the airport, it’s just as hectic, with more swarms of traffic, clattering luggage, planes roaring overhead and, in the middle of all this chaos, Heathrow’s tall radar; spinning round-and-round-and-round-and-round at a giddying speed… does that thing ever stop rotating? Just looking at it is exhausting!

*

Once your passenger is safely dropped off and pounding towards the check-in desk, it’s time to catch your breath and head back into central London.

You could of course rank-up at Heathrow, but that’s a complex process which involves paying for tokens and queuing in a large parking-lot, gazing up at a big, digital board which, after what seems like an eternity, will finally display your badge number and designated terminal. It’s a bit like waiting for the cheap kettle you ordered in Argos– only less fun.

Last time I tried to get a job from Heathrow, I had to hang around for almost four hours, so now I tend to head straight back into town and hope for the best.

*

As you head back towards London, the M4 motorway becomes elevated, and you are whisked high over the rooftops for some two miles. This section of the motorway is characterized by the large offices and car show rooms which flank each side of the road’s bridge.

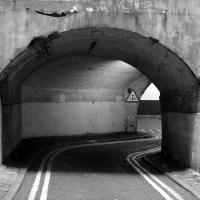

Part of the M4 elevated section in daylight (courtesy of Google Streetview)

Many of these buildings have massive, illuminated billboards sprouting out of them and speeding past them at night often conjures up thoughts of the futuristic film, Blade Runner.

Amongst this forest of neon, there is one sign in particular which, despite looking old fashioned and rather unassuming, has a special place amongst many Londoners’ hearts:

The Lucozade advert.

Fastened to the side of a building on York Parade in Brentford, the Lucozade sign is an iconic image which was first unveiled in 1954; years before the M4 flyover was even built.

The sign was an early example of ‘kinetic sculpture’; a display which boasted movement. In this case, the kineticism came from the glittering bulbs, which emulated liquid being poured into a glass.

The original sign (which even featured briefly in a 1975 episode of ‘The Sweeney‘) survived until 2004, when the building supporting it was demolished. Luckily, the 1950s display was carefully removed and is now housed in the nearby Gunnersbury Museum.

Following the building’s destruction, the famous sign which had welcomed weary motorists into London for so many years was sorely missed… so much so, that a campaign by local people was established; the aim being to get the retro Lucozade ad re-instated.

The campaign was a success and, in 2010, a replica was put up near the site of the original. As Culture Minister, Margaret Hodge quipped when the sign returned, “there was no energy lost in the campaign by residents.”

Thanks to the hard-won copy, the iconic image can now continue to shine throughout the night; a beacon, pouring its never ending stream of glittering glucose into an equally bright glass, just like its predecessor did for fifty years.

The sign’s original purpose- to advertise- must still be working too because, after my stressful trip to Heathrow, I really do feel the need to “replace lost energy” and stop off at the next available newsagent in order to purchase a bottle of good old Lucozade!

Tales From the Terminals: Euston. Part Two (1960s Euston)

By the early 1960s, the ability of Euston to play its role as a major railway station had once again become a major issue and, in 1961, British Rail decided that the old station was no longer capable of handling its operations.

To British Rail, the solution to this dilemma was simple- and also one commonly employed in the hastiness of 1960s planning…

With no regard for history or the beautiful Victorian architecture, Euston Station was completely demolished.

Even the much-loved Doric Arch wasn’t spared.

The Doric Arch, shortly before demolition

It is believed that the final go-ahead for this destruction was granted by the then Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan who was quoted as saying, “An obsession with such buildings will drain our national vitality.”

The annihilation of Euston caused outrage and was labelled as being, “one of the greatest acts of Post-War architectural vandalism in Britain.”

Sir John Betjeman (poet laureate from 1972-1984), along with the newly founded Victorian Society, had campaigned fiercely to have the old station spared.

In this case, they failed, but the indignation caused by the demolition was instrumental in changing attitudes towards old architecture, and their mission was to prove far more successful when it came to saving nearby St Pancras…. (something which I shall be exploring in the next instalment of this station series).

*

Euston Mark Two

The new and present Euston Station was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1968.

It is a building very characteristic of its time; modern, utilitarian and a fierce opinion-divider. A commenter in the Times suggested that, “even by the bleak standards of sixties architecture, Euston is one of the nastiest concrete boxes in London…”

Artistic impressions of the new Euston from a 1960s brochure

It must be remembered that the new Euston was built during an era of rapid social and technological change.

In the 1960s, British rail began to phase out steam engines in favour of diesel locomotives. Steam engines, with their plumes of smoke, required high-vaulted, well-ventilated buildings… diesel engines did not; hence the reason that the Euston we see today is a much lower, dimmer building.

In 1980, Michael Palin made a series for the BBC about Britain’s railways entitled ‘Playing With Trains.’ The documentary began at Euston Station, and Michael Palin was clearly unimpressed with the modern Euston!

The station was also constructed as jet-travel was becoming popular with the masses, and it is believed this was influential in the new Euston’s design. The modern building, with its broad waiting area, huge departure board, dotted information kiosks and long ramps is very similar in design to an airport terminal.

Euston Ticket Hall; then and now

In 1969, pop group, Slade (then known as Ambrose Slade and still a while away from their glam-rock heyday) filmed a very early promo at the brand-spanking new Euston.

Comparing this footage to Euston as it is today, it is surprising to see just how little the station has actually changed (although posters are now written in post-decimal currency!)

*

Abstract Art & Traces of the Old Euston

Outside the station, Euston’s piazza is a rather bleak affair, dominated by an office complex which was built during the late 1970s. Be thankful for small mercies though… British Rail originally envisioned a cluster of towering blocks to be built in the area. Luckily, Camden Council introduced height limits on new projects; thus ensuring the offices outside Euston were kept a little closer to the ground.

Placed rather unceremoniously amongst these windswept offices, you may come across this abstract sculpture:

Sculpted in 1980, this piece (dedicated to German theatre director, Erwin Piscator), was created by Eduardo Paolozzi.

Paolozzi (1924-2005) was a Scotsman; born in 1920s Edinburgh to Italian immigrants.

As discussed in my previous post about London’s ‘Little Italy’, anyone in the UK of Italian origin was detained during WWII. As a 16 year old teenager, Paolozzi was no exception… and, tragically, his uncle and grandfather were killed in the Andorra Star disaster.

After the war, Paolozzi became a noted artist, his style mainly being defined by hints of surrealism and an interest in modern machinery. His 1947 piece; I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything is considered the first major work in the Pop Art movement.

Paolozzi has a number of other public works spread across London. A short walk from Euston, outside the wonderful British Library, you’ll find his sculpture of Sir Issac Newton:

The ‘Head of Invention’ outside the South Bank’s Design Museum is another one of Paolozzi’s, as is what is probably one of the most viewed artworks in London- his colourful, 1980s mosaic designs which decorate the platforms of Tottenham Court Road tube station.

*

A tiny handful of items from the original, Victorian Euston can also be discovered around Euston Station’s dystopian precient.

One of them is a statue of Robert Stephenson (the main force behind the construction of the line), which once stood in Euston’s grand hall.

Exposed to the elements, and now situated amongst the 20th century modernity, Mr Stephenson stands rather defiant!

Further forward, facing the roar of the Euston Road, stand two ‘lodges’, between which the famous Doric Arch once stood. Today, they house two small pubs.

Speaking of the Doric Arch, lumps of it still remain today… although you’ll require a snorkel and diving gear if you wish to see them, as they are currently languishing at the bottom of the River Lea in East London!

Following the arch’s destruction, the rubble was sold in 1962 and used to plug a chasm in the river’s ‘Prescott Channel’ which lies just east of the Blackwall Tunnel Northern Approach.

In 2009, a number of the stones were recovered (mainly to allow large freight barges, carrying materials for the Olympic Park, to navigate the waterway)

*

Euston Mark Three ?

There are currently plans to give Euston Station a substantial makeover.

Taking advantage of this opportunity, The Euston Arch Trust (of whom Michael Palin is the patron) are currently campaigning to have a reconstruction of the old Doric Arch included as part of the redevelopment.

If given the go-ahead, it is hoped that the old blocks from the old arch, which have lain at the bottom of the River Lea for fifty years, will be incorporated into the reconstruction.

You can read more about the campaign here.