Waterloo seeks another deep link

After failing to achieve their goal of establishing a link to Trafalgar Square (please see Waterloo Part One) , the board of the London & South Western Railway consoled themselves in the belief that their station at Waterloo was merely temporary and hoped in time to bridge their line towards another vital London hub- the financial Square Mile.

Bank Junction during the Victorian period… goodness knows where the LSWR thought they’d be able to squeeze in a major railway terminal! (image: Victorian London.org)

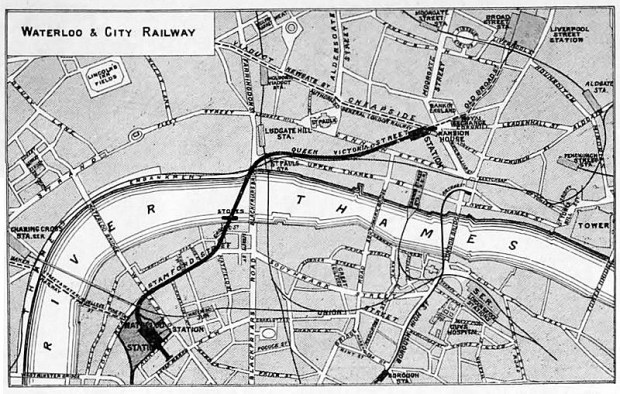

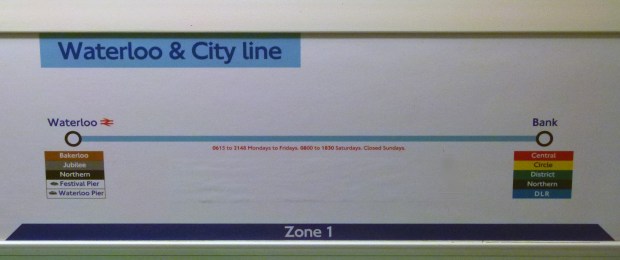

When this ambition also failed the company once again sought to reach their desired destination with an underground link- this time with far greater success…. giving us the ‘Waterloo & City Line’ which, with just two stations- one beneath Waterloo and the other beneath Bank Junction, is the London Underground’s shortest line…. “1 mile, 4 furlongs and 680 chains in length” as proposed in 1891.

Work on what was originally dubbed the ‘Waterloo & City Railway‘ commenced on the 18th June 1894 with the sinking of piles near Blackfriars Bridge; the line’s approximate mid-point.

Original map of the Waterloo & City Railway, tracing its path beneath Stamford Street and Queen Victoria Street.

Construction was carried out by John Mowlem & Co Ltd, whose other London works include Admiralty Arch, Battersea Power Station and Tower 42 (formerly the NatWest Tower).

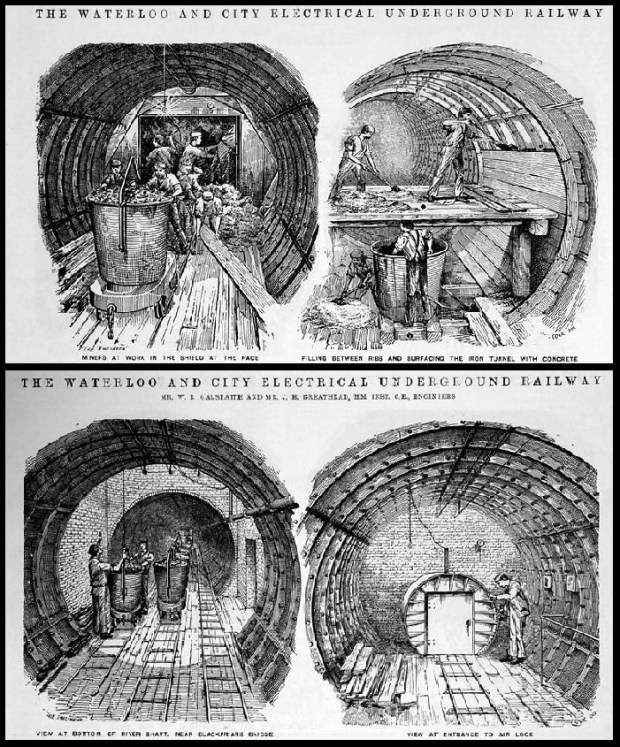

Pioneering Tunnelling

The Waterloo & City Railway was London’s second deep level tube line- the first being the City & South London Railway (now part of the Northern Line) which had opened shortly before in 1890.

Both of these pioneering lines could not have been tunnelled without the aid of the ‘Greathead Shield’; a tunnelling system named after its South-African born inventor, James Henry Greathead.

Essentially an updated version of an earlier system devised by Marc Isambard Brunel, the Greathead Shield consisted of a sturdy metal tube which allowed workers to burrow at a far deeper level, pushing through London’s clay at an average of 10ft a day and installing the tunnel lining behind them as they went.

Sadly, James Henry Greathead died in 1896 aged just 52 and never lived to see the completion of the Waterloo & City Railway.

A statue of the great engineer was placed outside the Royal Exchange in 1994 directly above Bank Station. The plinth upon which Greathead’s figure stands acts as a ventilation shaft for the tunnels below.

During the construction of the Docklands Light Railway in 1987, part of Greathead’s shield was discovered buried deep in the earth beneath Bank. This surviving piece can be seen today at Bank station, having been incorporated into a pedestrian subway linking the DLR to the Waterloo & City Line- just look for the distinctive red arch…

*

London’s New Tube

At 1pm on July 11th 1898 the Waterloo & City Railway was officially opened by the Duke of Cambridge whom the board of directors treated to a grand luncheon in the new railway’s Waterloo booking hall- which was described as being “capacious enough to afford ample accommodation to the whole of the assembled company.”

An 1890s leaflet advertising the opening of the Waterloo & City Railway (image: London Transport Museum).

The earliest trains to serve the Waterloo & City Railway were built by the Jackson and Sharp Company of Rochester USA, requiring them to be shipped across the Atlantic.

Although derided by The Times as being “decidedly ugly”, the wooden carriages were praised for affording the “maximum accommodation consistent with the diameter of the tunnel- namely 12ft 2inches.”

The American cars remained in use for over 40 years by which point they were beginning to look decidedly shabby. In 1937, one disgruntled commuter described the rolling stock as “antique and uncomfortable”, “musty and dingy” with “lighting arrangements 25 years behind the times.”

The ageing coaches were finally replaced in 1940 by sleek, Art-Deco style metal carriages which were ultra-modern for their time and remained in service well into the 1990s. Archive footage of the new carriages arriving (and the old ones departing) can be viewed below:

Up until the 1990s, the Waterloo & City Line- which has been nicknamed ‘The Drain’ since its earliest days- was run separately from the rest of the tube, first by the South Western Railway and then by British Rail. This set-up made it something of an anomaly, best illustrated by the livery of the carriages which were painted to match their larger, above-ground counterparts.

The Waterloo & City Line in ‘British Rail Blue’, used from the 1960s to the 1980s (image: Wikipedia).

Waterloo & City carriage appearing in an open day above ground in 1988. The livery here is of ‘Network South East’ used from the 1980s to the 1990s (image: Geograph).

The Waterloo & City shuttle service was finally absorbed by London Underground in 1993 with the 1940s rolling stock replaced by trains similar to the ones now used on the Central Line.

*

Because the Waterloo & City Line exists entirely underground, carriages requiring maintenance above ground are winched in and out by a specially designated crane which can be seen beside Waterloo station’s Baylis Road entrance.

During the delivery of the 1940s stock, the winch (which was originally situated where the now defunct Eurostar terminal stands) snapped sending one of the carriages smashing down to the depths…

A peek over the crane pit allows train-buffs a glimpse into the Waterloo depot…

All Change

As well as the Victorian carriages the entire infrastructure of ‘the drain’ was also beginning to look very dilapidated by the 1940s and was described in one meeting at the Guildhall a being a “public disgrace.”

Of particular concern was the main pedestrian link at Bank Station.

Unlike other underground stations served by lifts and escalators, Bank’s main link to the deep platform was a long, steep, dusty tunnel of incremental steps, notorious for being a dangerous, crushing bottleneck in which “hundreds of people meet head on and often collide….in the rush hour complete chaos reigns in the tunnel.”

So strenuous was the passage to negotiate that those of a more mature age were advised to avoid the link altogether, the steep tunnel at Bank being “quite an effort for elderly men and not without danger to anyone suffering from a weak heart.”

Although an escalator was proposed as early as 1931 the plan never went through and further attempts at modernization were halted by the onset of WWII.

The Waterloo & City Line finally received a drastic update in autumn 1960 with the introduction of a ‘Travelator’; Britain’s very first major moving walkway.

Taking three years to construct, the pioneering design was built to whisk 10,000 commuters per hour to and from the trains… and no doubt led many Londoners in the early 1960s to dream of an exciting new future in which moving pavements across the capital would become the norm!

*

The Waterloo & City Line on Film

Due to being primarily aimed at weekday commuter traffic, the Waterloo & City Line has always been closed at weekends (although a Saturday service has recently been introduced).

Waterloo and City Line’s platform at Waterloo. Take a train on a Saturday and you’ll pretty much have the place to yourself.

Because of this regular closure, the line has often proved popular with filmmakers, most notably in the 1998 romantic drama, Sliding Doors starring Gwyneth Paltrow in two parallel storylines which split as she attempts to board a Waterloo & City Line train.

Eagle-eyed viewers will notice that Gwyneth enters the system at Bank but boards her train at Waterloo on the opposite side of the line! (Please click below to watch a clip):

The line has also been used for sci-fi T.V classics such as Adam Adamant, The Tripods and Survivors.

In 1962, wannabe cop, Norman Wisdom found himself in a particularly sticky situation on the Waterloo & City Line after attempting a misdirected citizen’s arrest in his film, On the Beat (please click below to view)…

*

[…] Potted history of the Waterloo and City Line. […]

As one who used to work on the W&C in BR days, before it was handed to LUL, I find the history of my old work place interesting – thanks for sharing.

Many thanks, David. It’s always wonderful to hear from people who have direct links with the subjects I write about 🙂

I remember those old blue tin cans back in the 80s when I used to work in the city as a teenager. The trains had the electrical switch gear partioned from the passengers. You could peer through into the electrical room and listen to the clicking and clacking of the relays. I remember riding up front once in the driver’s cab and the driver telling me about the trackside blue fire lights, which would flash past every few seconds. I always thought it strange why there are so many twists and turns. I guess they tunneled around foundations. The drain always fascinated me, so I appreciate your writing once again.

Thanks, Sam- nice memory 🙂

Great stuff, knew about Greathead’s statue, but didn’t know it was also a vent too!

Tbe Drain’s had a Saturday service, going back to it’s BR days, though it was only until the early afternoon. Before that winch for lowering and raising the rolling stock, there was a lift on the track bed to get the rolling stock out for maintenance and back again. The winch had to be put in place after the lift was lost with the mainline upgrade for the Eurostar services. The current rolling stock was bought by BR, when the Central Line had it’s trains made, as an extension to the order. Not surprising, as they were made by BREL, which was when BR made their own trains. They were in full Network South-East livery, with BR double arrows instead of the Underground bullseye. Plus, as the line was BR operated and owned, it operated on the third rail system, so the trains were made for that system. When the line was taken over by London Underground, the whole line had to be converted to their four rail system, along with the trains.

Strictly speaking, you can’t really call the moving walkway at Bank a Travolator anymore. The Travolator was replaced back in the ’90s, but not by the Otis company who own the name, so it’s just a moving walkway now. Also means LU can’t call it a Travolator anymore either.

Thanks, Darren 🙂

Sorry darren, the fourth rail was installed some years before LU took over, when the new trains were introduced (these, like the Central Line trains which formed the major part of the build, have always been four-rail).

Interesting to note that this was the third electrification system used on the line – the 1940 upgrade included moving the live rail from the originbal 1898 central positoin to the side position which had become standard “upstairs”. This allowed the 1940 stock to operate on the main line to go for major maintenance at Wimbledon – although the lack of windscreen wipers meant the staff had to cosnult the weather foirecast first!

Have to disagree with you SW commuter, as a user of the line I remember the trains using the third rail system, then just after LU took over in 2006, the line was closed for several months to upgrade to 4th rail. I had an argument about this with someone on YouTube who’d posted a video of the line and stated they were 4th rail from the get-go, but there was pretty much 100% agreement with me from other comments left, that the trains were originally built for third rail use, as there were no plans to transfer the line to LU at that time. Those trains were brought in before British Rail was broken up for privatisation and were built to BR specifications, by British Rail Engineering Ltd (BREL) in 1992 as an additional order to LU’s.

EDIT: Should say line transferred over in 1994, not 2006

[…] to Black Cab London, the previous crane (which stood where the now disused Eurostar platforms are) snapped in the 1940s […]

[…] to Black Cab London, the previous crane (which stood where the now disused Eurostar platforms are) snapped in the 1940s […]

[…] of new light on our bronze age history. More up to date and in London here’s part 3 of the history of Waterloo Station. Here’s something I bet you Londoners didn’t know about. Roaming the Thames with Thames […]