Long Lost Dread: The Millbank Penitentiary

Overlooking the river Thames on Millbank, the Tate Britain gallery enjoys a pleasant and relatively tranquil location.

It may come as some surprise therefore to learn that the site was once occupied by an altogether different building; a place of dread and great suffering known as the Millbank Penitentiary.

By the 18th century, long term incarceration, hard labour and transportation to Australia were becoming increasingly popular punishments (as opposed to more traditional forms such as the stocks and public beatings).

The gaols and hulks (prison ships) however were ill equipped to deal with the increasing numbers of convicts and found themselves plagued by bad-management, overcrowding and brutality, the dire consequences of which led campaigners to push for reform.

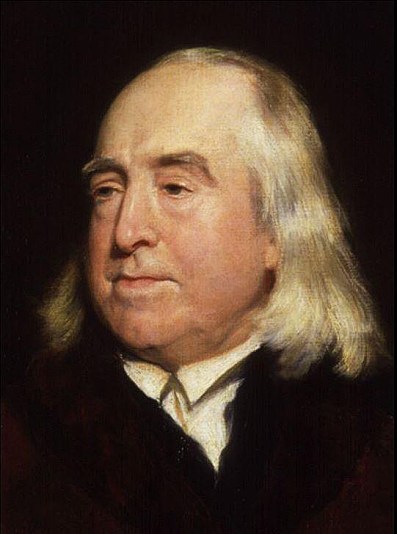

Once such proponent of change was Jeremy Bentham, a forward thinking philosopher and social reformer who played a key role in founding London University, the institution which would go on to become today’s University College London.

Rather bizarrely, Bentham’s preserved body is kept on public display in the university to this day… click here to see a rather unsettling 360-degree view!

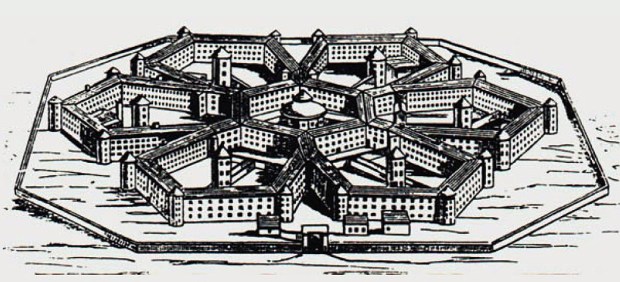

Believing prisoners should be held in a safe, clean- albeit tough- environment, Jeremy Bentham drew up plans for a new type of gaol- the Panopticon; a circular prison in which cells are arranged around a single watch tower.

Taking its name from the Greek for ‘all seeing’ and described by Bentham as “a mill for grinding rogues honest,” the theory behind the Panopticon was that the constant surveillance of inmates would condition them to behave.

Looking to put his proposal into practice as Britain’s first national penitentiary, Bentham purchased a marshy patch of land by the Thames in 1799. The area was named ‘Millbank’- after a mill which once belonged to Westminster Abbey and stood on the site.

After numerous obstacles however Bentham’s scheme was abandoned and in 1812 a competition was held to find a new design.

This was won by William Williams, a military man based at Sandhurst, whose idea was taken on by architect, Thomas Hardwick… who resigned in 1813. Hardwick was replaced by John Harvey… who was sacked in 1815.

Finally, the increasingly troublesome project was handed over to Robert Smirke, the architect who would later go onto design the British Museum.

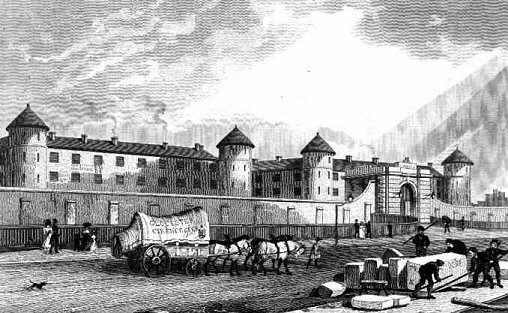

Being marshy, the prison’s chosen site presented many problems for builders when it came to setting foundations. Smirke tackled this by laying a large concrete raft into the sodden ground. Unsurprisingly, costs began to run high, finally totalling half a million pounds (approximately £17 million in today’s money).

When it finally opened in June 1816 the Millbank Penitentiary was the largest prison in Britain.

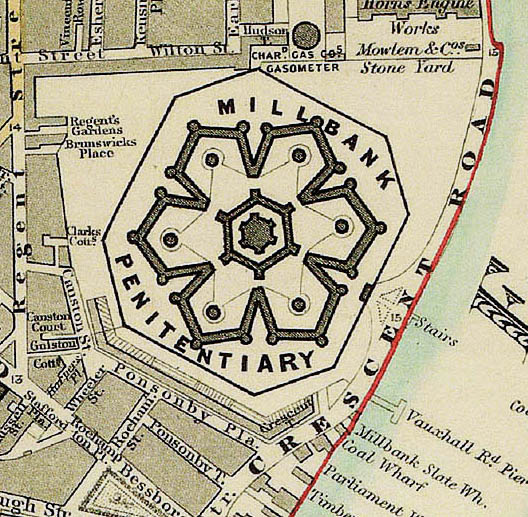

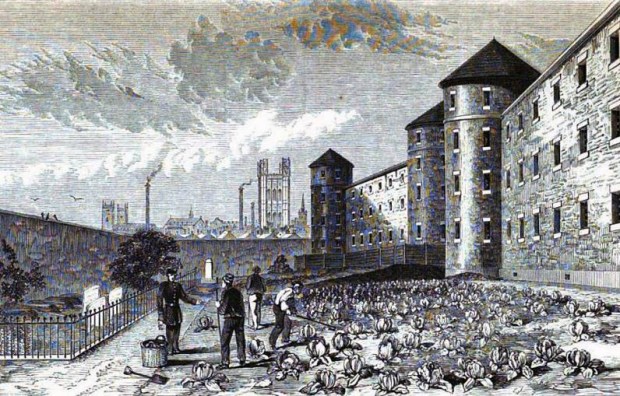

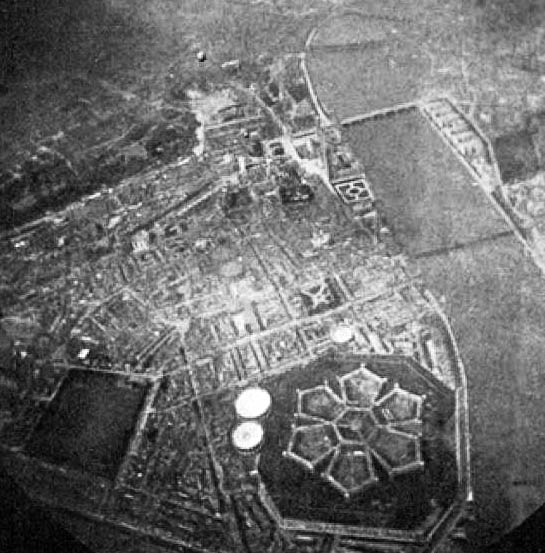

Forged from Scottish Collalo stone, the penitentiary was set out in a hexagonal shape encompassing six petal shaped wings, each three stories high and each containing five courtyards, all of which surrounded a single chapel in the centre.

If this layout sounds confusing, then that’s because it was- even the guards struggled to navigate their way around the grim labyrinth.

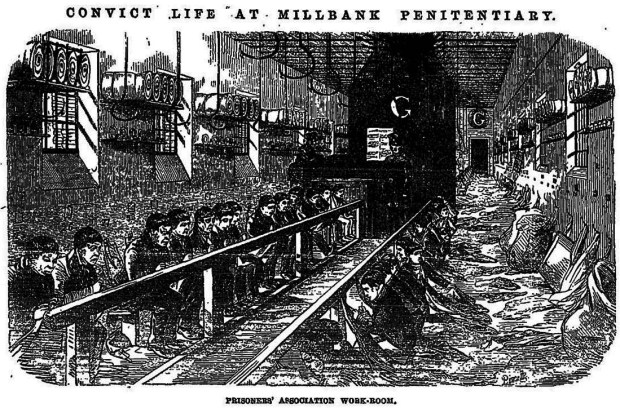

A revealing description of the penitentiary was printed in the Penny Illustrated Paper in October 1865:

“If the ground-plan of the building at Millbank is a geometrical puzzle, the interior is assuredly an eccentric maze. Long, dark and narrow corridors and twisting passages, in which the visitor unaccustomed to the dubious twilight has to feel his way; double-locked doors opening at all sorts of queer angles, and leading sometimes into blind entries and frequently to the stone staircases… so steep and narrow are not unlike the devious steps by which the traveller reaches the towers of Strasbourg and some other cathedrals, except that they are even more gloomy.”

Steps inside Strasbourg Cathedral, which were said to resemble those within the Millbank Penitentiary (image: Midnight Cafe)

The first group of prisoners to enter the Millbank Penitentiary were all female, the first male contingent arriving seven months later in January 1817. Although sentenced to transportation, these convicts were considered capable of redemption and had therefore been offered jail sentences of 5 to 10 years in lieu of banishment to Australia’s Botany Bay.

In hindsight however those sent to Millbank may have wished they’d been shipped to Oz after all.

Conditions in the newly built complex were atrocious, with minimal rations of bread and water, a mere five minutes of exercise per day and the formation of “jealous cabals” amongst the wardens which encouraged a “system of malicious tale bearing.”

Worse was to come though, with regular outbreaks of cholera, malaria, dysentery and scurvy thriving within the poorly sanitised gaol.

The Morning Chronicle gave a damming report of conditions in July 1823:

“The two chief sources of disease, incident to man, are marsh-miasmata and human effluvia. In the Penitentiary these sources are not only combined but concentrated. It is seated in a marsh, beneath the bed of the river, through which the vapours from stagnant water are constantly exhaling.

The effluvia from the mass of human beings confined within its walls cannot dissipate from deficient ventilation. These causes operating upon a crown of persons, whose minds are depressed by the prospect of lingering confinement, cannot fail to produce all the disease which take place in the Lazar-house; scrophula, scurvy, prostration of strength, and fever of the worse description.

To these sources of disease must be added the malaria from the muddy banks of the river, which renders the whole vicinity unhealthy…

There is but one remedy- to place as much gun powder under the foundation as may suffice to blow the whole fabric into the air. Whether it would be an act of humanity, previously to the removal of the prisoners, may be a fit subject for discussion by those sapient persons who first sanctioned the erection of such a structure on such a site.”

Others dubbed the prison “an English Bastille” and noted that Jeremy Bentham would have been horrified by the monstrous design which had replaced his original, forward thinking vision.

The awful conditions within the Millbank Penitentiary are illustrated by the death of an inmate called Henry Harror, a 24 year old who’d been imprisoned for stealing a horse. In a report, Henry’s body was described as “a skeleton presenting nothing but skin and bone.”

*

As well as disease, stench and hunger, prisoners were expected to remain silent at all times, and those breaking the rules could expect solitary confinement, shackling or whipping- although this fierce reprimand was reserved for those committing offences of “exceptional violence and brutality.”

Considering these conditions it’s perhaps no surprise that numerous escape attempts were made – such as two “notorious fellows”, Meggs and Carey who succeeded in fleeing after leaving dummies- complete with nightcaps- tucked in their beds.

Dummy head… this one was used in the 1962 breakout from Alcatraz in the USA. Clearly a vital tool for inmates looking to escape!

After crawling through a ventilation hatch, scaling the wall and donning soldier’s uniforms, the pair managed to flag down a hansom cab which whisked them away. Despite their efforts however the two fugitives were quickly recaptured the following day on Britannia Street near King’s Cross.

*

By May 1843 the prison had sunk into such degradation that Parliament decided the facility was no longer fit for holding inmates long-term.

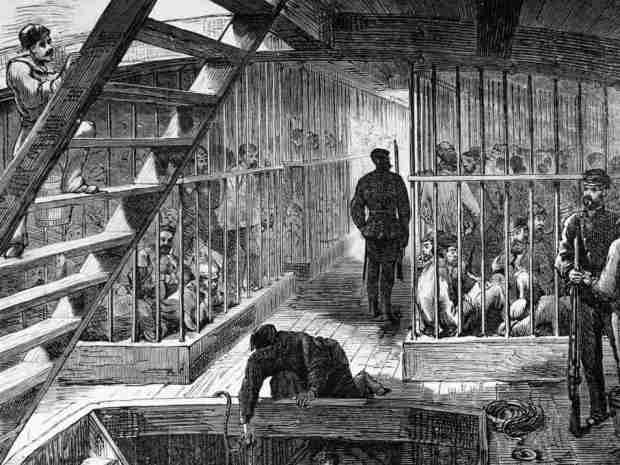

The ‘model prison’ role was taken over by Pentonville which had opened on Caledonian Road in 1842, leaving the Millbank Penitentiary to be demoted to a “general depot for all convicts”; a holding facility in which those sentenced to transportation were held (usually for three months) until a place became available on one of the dreaded prison ships bound for the Australian penal colony.

Caged convicts on a ship bound for Australia. The average journey time to the penal colony was 102 days

One of the first send-offs in early 1844 was described in the London Illustrated News:

“A large number of convicts, under sentence of transportation were removed from the Millbank prison and placed on board the Blundell and the London transport ships… the London (a fine vessel of 700 tons burden) takes out 250 of the lighter class of offenders, and is bound for Hobart Town. The Blundell carries 210 of the worse class, her destination being the penal settlement of Norfolk Island.”

*

Two years after the prison’s switchover to transportation duties, the nearby Morpeth Arms pub opened next door, mainly for the refreshment of the prison’s wardens.

The pub survives today and legend has it that a network of vaults beneath the building are the remains of an old service tunnel (haunted by a former inmate, naturally), used to escort prisoners from the gaol to the riverbank for their departure.

Some believe prisoners nicknamed this procedure “going down under” which in turn led to the popular colloquial term for Australia. Although other sources suggest prisoners were marched above ground via the prison’s main gate, thus making Millbank the last piece of British soil convicts would be in contact with.

It is also said another Aussie slang term; ‘pom’ is an abbreviation of ‘Prisoner of Millbank’…

P.O.M ‘Prisoner of Millbank…’ The uniform worn by those held in the Millbank Penitentiary was “rust brown” in colour with a purple stripe

*

Transportation continued until the late 1860s by which point around 162,000 men and women had been sent to Australia.

Today, a bollard used to moor boats which would transfer convicts downstream to the awaiting, larger prison ships at Woolwich Arsenal can still be spotted beside the Thames, just across from Tate Britain.

*

Once transportation ceased in 1867 the Millbank Penitentiary reverted to being a regular gaol and then, in 1870 a military prison.

During this period, one of the inmates was Michael Davitt, an Irish Republican prisoner who wound up in Millbank as a young man.

He described hearing the chimes at Westminster; the Houses of Parliament being a short distance away:

“Westminster Clock is not far distant from the penitentiary, so that its every stroke is as distinctly heard in each cell as if it were situated in one of the prison yards… day and night it chimes…and those solemn tones stroke on the ears of the lonely listeners like the voice of some monster spirit singing the funeral dirge of Time…”

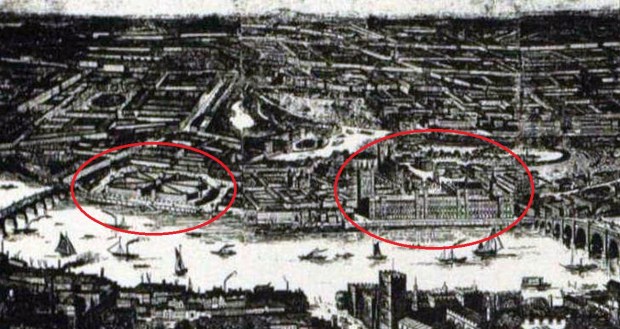

Contemporary sketch of the Thames showing the proximity of Millbank Penitentiary to the Houses of Parliament

*

The Millbank Penitentiary finally closed in 1890 and the lengthy demolition process commenced two years later.

In 1899 whilst the prison was still being flattened, sugar magnate, Sir Henry Tate donated his collection of 65 paintings to the government along with a donation of £80,000 for the construction of a gallery in which to house them.

Despite “not being near South Kensington” and understandable fears about the dampness which had plagued the prison, the large, vacant Millbank site was chosen for the construction of the National Gallery of British Art– which we now know as Tate Britain.

The gallery opened in 1897 and the remaining vacant land became home to a housing estate, the Chelsea College of Art and Design and the former Royal Army Medical School.

*

Today, the angled street layout surrounding Tate Britain gives some idea as to where the Millbank Penitentiary once stood.

A perimeter trench which once surrounded the prison (and which would’ve been filled with stagnant water) can still be seen alongside Willkie House on Cureton Street– it is now used for drying laundry and growing vegetables.

Over the years, excavations have also turned up other remnants.

In 1959 a metal object was located 14ft down, although engineers were not sure whether it was an unexploded bomb or a heavy prison door… it may indeed still be buried down there.

In the 1980s when the gallery’s Clore wing was being built, remains of underground cells were found. Further building works in the late 1990s discovered old wall foundations and evidence of the concrete raft originally laid down by Smirke to combat the marshy land.

A rare photograph of the now vanished Millbank Penitentiary, taken from a balloon in the late 19th century

***

Waterloo’s Dark Side (Waterloo Station Part 9)

Over the years, Waterloo station and its cluster of surrounding streets have seen more than their fair share of life’s darker side…

The Lambeth Poisoner

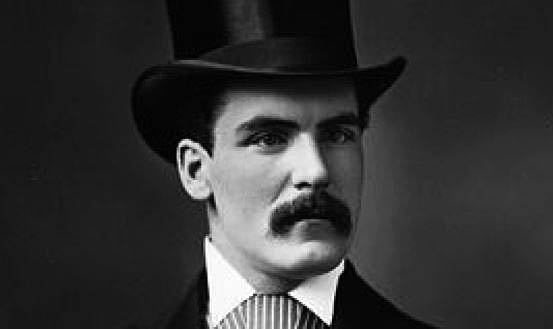

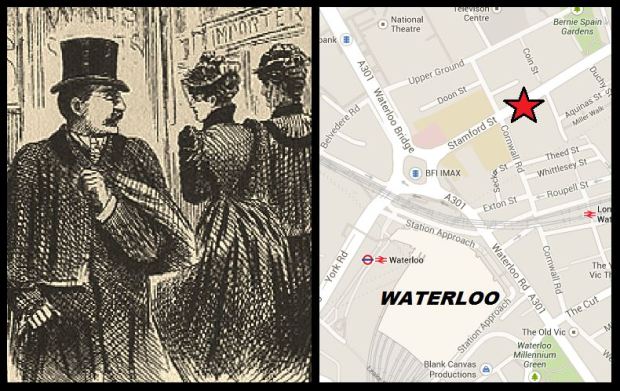

In the autumn of 1891, the area around Waterloo was stalked by Dr Thomas Neill Cream, a Glaswegian born physician and surgeon who’d spent much time in Canada and Chicago running decidedly dubious clinics.

Following the mysterious deaths of several of his patients and a 10 year stint in Chicago’s Joliet prison, Dr Cream headed for London where he secured lodgings at 103 Lambeth Palace Road.

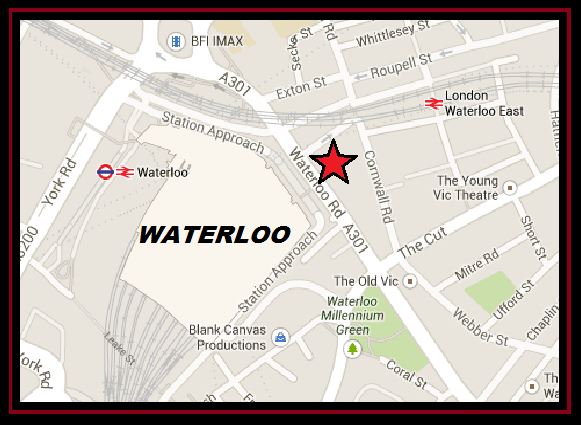

Approximate location of Dr Cream’s lodgings and Lambeth Palace Road today (please click to enlarge map)

Shortly after his arrival, the Doctor popped into the Wellington pub on Waterloo Road and got chatting to a 19 year old prostitute named Ellen Donworth.

Ellen accepted a drink from Dr Cream… and later that night, she collapsed outside the pub.

Trembling and in great pain, she claimed she’d been poisoned.

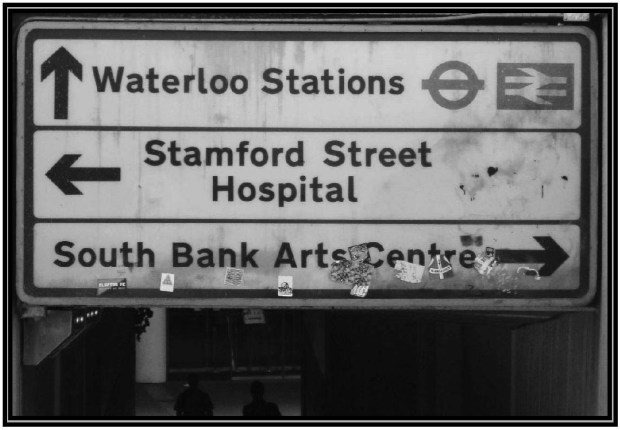

Dr Cream’s next targets were Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell, two young women who lived together on Stamford Street, just north of Waterloo station.

After plying the pair with bottles of Guinness, the doctor handed the women some globule like tablets which, when swallowed, led the victims to suffer painful, fatal convulsions.

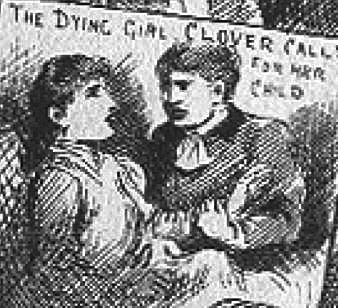

Creams’ final victim was Matilda Clover, a young mother who lived on Lambeth Road.

As she lay screaming and dying on her bed, Matilda managed to tell her landlady, “that wretch has given me some pills and they have made me ill…”

In each case, the killer never hung around to witness the terrible results of his gruesome handiwork.

Dr Cream was captured after befriending an American tourist…who happened to be a New York cop.

After listening to Cream speak in revealing detail about the crimes, the American voiced his concerns to Scotland Yard. Following the tip off, Dr Cream was put under surveillance… and his behaviour soon confirmed the New Yorker’s hunch, leading to the suspect’s arrest.

Tried at the Old Bailey, Dr Cream was found guilty and executed at Newgate in November 1892.

Curiously, it is said that his final words, uttered as the trap door sprang, were, “I’m Jack the…”

*

Killed in a carriage

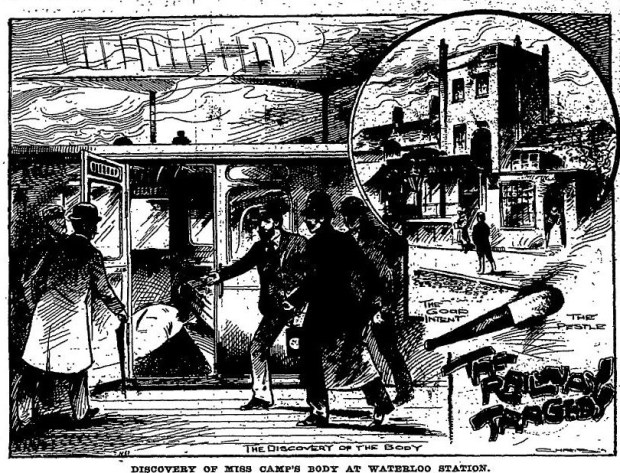

On the evening of 11th February 1897, Elizabeth Camp– 33 year old manageress of the ‘Good Intent’ pub, on East Street, Walworth– was found battered to death in a carriage shortly after it pulled into Waterloo station.

Tragically, Elizabeth’s fiancé, Edward Berry was waiting on the platform to meet his lover and witnessed the ghastly commotion as the body was discovered.

It was believed that the main motive had been robbery and Elizabeth, who was described as a large, “formidable” woman, had put up a tough fight.

The apparent murder weapon- a chemist’s pestle caked in blood and hair– was soon discovered on a nearby railway embankment, leading investigators to suspect that the killer had boarded the train at either Putney or Clapham Junction.

Despite this, along with reports of a mysterious, flustered man nervously ordering a drink at a tavern in Vauxhall, the killer was never caught…

*

A disturbing discovery

In February 1935 a large, brown parcel was found stuffed beneath a seat in a carriage at Waterloo station which, when opened, gave railway staff a terrifying shock… for the package contained a pair of human legs, neatly severed from the knee down.

The following month, three young boys playing beside the Grand Union Canal in Brentford towards the west of London, spotted a sack floating in the water. Their curiosity got the better of them and they dragged the object towards them for a nosy peek…only to find that it contained a headless, legless torso…

The parts were examined by pathologist, Sir Bernard Spilsbury who declared that they were part of the same body.

Sir Spilsbury believed that the victim had been a healthy young man, aged between 20-30. He also noted that the victim may have been a dancer as the toes on the chopped off legs appeared to have been slightly contracted by tight-fitting shoes.

However, like the murder of Elizabeth Camp years before, the case remains unsolved…

*

Modern fears

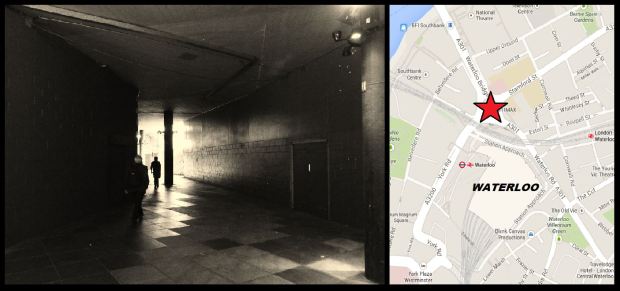

By the 1970s the streets and walkways surrounding Waterloo station had gained a reputation as a grimy and increasingly crime ridden area.

One evening in August 1973, 68 year old widower and retired railway worker, Graham Arthur Hills was returning home after an evening at the theatre. On a raised walkway linking the Shell Centre to Waterloo station, he was confronted by three youths aged 15, 16 and 17 who mugged the elderly gentleman.

After a struggle, Mr Arthur Hills was stabbed in the heart and killed… his briefcase, which contained no more than a single prayer book, was found discarded close by.

*

The murder of PC Frank O’Neill

On the 10th October 1980 two police officers- PC Frank O’Neill and WPC Angela Seeds– were called to a disturbance at a Boots chemist shop on Waterloo’s Lower Marsh where Josun Soan, a drug addict from Wembley, was attempting to acquire drugs with a forged prescription.

Suspicions had initially been raised when the chemist queried the note’s handwriting… saying it was far “too neat for a doctor.”

As PC Frank O’Neill approached, Soan lashed out and stabbed the officer in the stomach- he would later claim in court that he’d been hallucinating and mistook the policeman for a “big brown bear… I saw it out of the corner of my eye, which scared the living daylights out of me…I got a knife out and slashed in that direction and then ran out of the shop.”

PC O’Neill gave chase but collapsed to the pavement and later died. He was 32 and father to four children.

His colleague, 25 year old WPC Seeds bravely continued the pursuit, finally cornering the killer on a platform at Lambeth North tube station.

Josun Soan was tried at the Old Bailey in May 1981. At the time he was 23 and had been a drug addict since the age of 14. He was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Following the crime, donations for Frank’s widow and children poured into police stations across London.

‘Frank O’Neill House’ on Clapham Road, is named after the fallen officer.

*

Ward 5’s Medical Horror

Just across the road from Waterloo station stands the former ‘Royal Waterloo Hospital for Children and Women’ which was founded in 1816 (the current building was constructed between 1903-1905).

Between the 1960s and 70s the hospital was home to the notorious ‘Ward 5’; a unit where some 500 women suffering from depression and anorexia were subjected to horrendous experiments, completely disproportionate to their condition.

Ward 5 was under the charge of William Sargant, a cold, imposing man who described himself as a “physician in psychological medicine.”

Rejecting psychotherapy, Sargant approached the treatment of mental illness as if he were dealing with a physical ailment, believing it was possible to rewire the brain.

In his quest to achieve this, Sargant treated the unfortunate women who passed through Ward 5 as guinea pigs, subjecting them to high drug doses, frequent sessions of electroshock therapy and, in some cases, lobotomies.

A windowless chamber on the top floor of the hospital was set aside as a ‘Narcosis Room’ where many female patients were drugged into deep sleeps for weeks on end.

One patient, Elizabeth Reed (who was admitted to the hospital when she was just 22), recently gave a disturbing account of the room;

“Women there were occasionally woken to be taken to the toilet or fed. We were like zombies… the worst times was when I started not to be asleep. I was awake but couldn’t move or speak. It was torture lying there for hours in the darkness.”

The Narcosis Room remained in use until 1973 (despite the death of four women whilst in their induced comas) and the hospital closed in July 1976.

Sargant continued to work at nearby St Thomas’s Hospital until his death in 1988. He personally destroyed all of his records.

The former Waterloo hospital is now a student hall of residence.

*

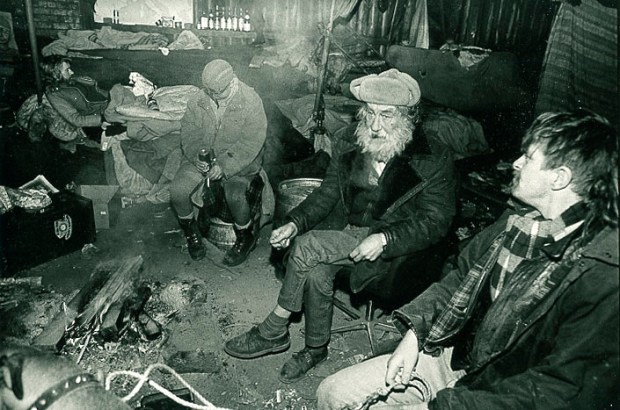

Cardboard City

For much of the 20th century, Waterloo station and its surrounding walkways became synonymous with London’s homeless who congregated in the area to sleep rough.

By the early 1980s an entire community- dubbed ‘Cardboard City’- had developed beneath the ‘Bullring’; a concrete roundabout at the foot of Waterloo Bridge.

By the middle of the decade, up to 200 people were living in the subterranean area.

Conditions in the concrete complex were harsh to say the least. In 1988 for example a broken sewer unleashed a colony of rats which crawled over the inhabitants as they slept.

In 1998, the High Court granted an eviction order against the 30 destitute people who remained in the makeshift community… so that the area could be prepared for the construction of the huge IMAX cinema.

I wonder how many visitors to the imposing venue realise that Britain’s largest cinema screen stands on the site of what was once the nation’s largest homeless community…

A slideshow of the area as it appears today can be viewed below.

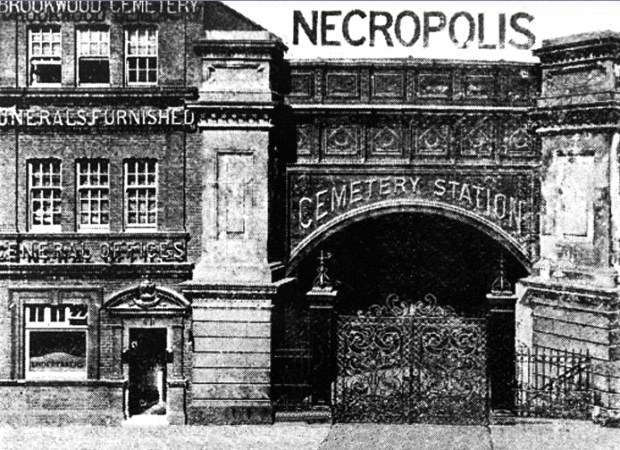

Tales From the Terminals: Waterloo Station (Part 4… Death Line… The London Necropolis Railway)

When Waterloo station opened in 1848 the Industrial Revolution was at full steam, nudging the population of London towards an unprecedented 2.5 million people.

As families packed into cramped, decrepit housing amongst appalling sanitation, regular outbreaks of smallpox, cholera, typhoid and various other diseases became commonplace… in 1850, the average life expectancy for those living in the capital stood at just 43.

With Londoners dying in such vast numbers the city’s graveyards quickly found themselves overwhelmed and unable to cope. Southwark’s Cross Bones burial site for example was so packed by the early 1850s that there were reports of fresh corpses poking through the thin layer of topsoil.

In response to this burial space crisis an Act of Parliament was passed in 1852 which established the London Necropolis & Mausoleum Company, a group charged with the task of creating a single, massive cemetery- a ‘City of the Dead’- where it was hoped all of London’s corpses could be interred.

A plot for the huge burial site, with the “requisite qualities of solitude and retirement” was secured 25 miles outside of London at Brookwood on Woking Common, Surrey.

At 500 acres, the cemetery was the largest in the world when it opened and is still the biggest in Britain today.

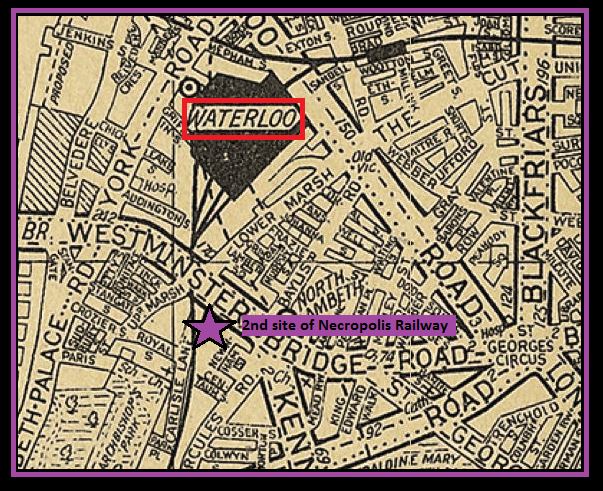

Although the new cemetery lay some distance from the capital the LNMC intended to maintain a firm connection with a unique innovation…the ‘Necropolis Railway’; a private transport link scheduled to operate out of London’s Waterloo.

Waterloo was chosen due to its proximity to the Thames (sites at Battersea and Nine Elms were also considered for the same purpose); the idea being that bodies could be delivered easily to the station via river from most parts of the metropolis.

After being unloaded from the boat, coffins would be placed upon a horse-drawn hearse for the short trot to the Necropolis station which, although incorporated into Waterloo, was kept distinctly separate from the rest of the terminal with discretion considered the utmost priority.

Once at the private station, coffins would be transferred up to platform level via a steam-powered lift and loaded onto an awaiting funeral train.

Mourners of the deceased would also board the service, taking time to grieve in special waiting rooms before embarking on the 45 minute journey to Surrey.

Like other rail services at the time, passengers- both living and dead- had a choice of three classes.

Whilst first and second class mourners travelled in comfort and had a say in the funeral’s arrangements, third class carriages were designated for paupers whose cheap tickets and flimsy caskets were paid for by their local parish.

As well as class, the carriages for both coffins and passengers were also segregated along religious lines- with separate coaches for Anglicans and Nonconformists.

Upon arrival at Brookwood, the funeral train would shunt onto a branch line which ran directly into the cemetery. Two stations served the necropolis; the north terminal for Nonconformist burials and the south terminal for Anglicans.

As with Waterloo, each station at Brookwood contained segregated waiting areas… and licenced refreshment rooms, which could prove rather tempting for railway staff as they awaited the return journey- there is at least one recorded occasion of an engine driver becoming so drunk his fireman had to drive the train back to London!

*

On the 7th November 1854 Brookwood Cemetery was consecrated by the Bishop of Winchester and the Reverend L. Humbert of St Olave’s, Southwark who travelled to the ceremony on-board one of the new state of the art services.

Several days later, on the 13th November 1854, the Necropolis Railway was ready for its first booking- a tragic pair of baby twins who had been stillborn to a Mr and Mrs Hore of Ewer Street, Borough.

Although the Necropolis Railway was contracted to take the bodies of London’s paupers it was a duty which the company approached with typical Victorian disdain towards the poor; an attitude which led to considerable controversy during the railway’s early days…

With first and second class burials taking priority, problems arose as bodies of society’s less fortunate began to pile up.

As a quick solution, the company decided to stash the surplus corpses inside a series of arches stretching from beneath Waterloo station up to Westminster Bridge Road- a viaduct which, at the time, cut through the most densely populated area in Lambeth.

An old arch- now in use as a car wash- close to the location of the Necropolis Railway’s former Waterloo base.

When this grim practice was exposed concerns were raised that the corpses, languishing “in the last stage of decomposition” and “heaped up together like so many bales of worthless goods,” would potentially spread disease within the neighbouring community and would send a foul “effluvium” wafting up through Waterloo’s platforms.

The Times also voiced the opinion that local businesses would suffer as people- “especially ladies”- would be inclined to avoid the area…

*

At the turn of the 20th century Waterloo station underwent a large expansion which required the Necropolis Railway terminal to relocate a short distance away to Westminster Bridge Road.

Although the first Necropolis site has been swept away leaving no trace, part of its successor, which opened in 1902, can still be seen today. The remaining building is now an unassuming office block known as Westminster Bridge House.

Like its predecessor, the second Necropolis station was furnished with a coffin lift and waiting rooms divided by class and religious belief. An oak panelled chapel was also incorporated where mourners not wishing to catch the train to Brookwood could pay their final respects.

*

When first conceived, it was forecast that Brookwood Cemetery would take up to 50,000 burials per year.

However, as large cemeteries within London such as Kensal Green, Tower Hamlets and West Norwood developed, ‘passenger’ numbers on the Necropolis Railway dwindled- the figures no doubt also affected by improvements in London’s sanitation and the formal introduction of cremation in the late 19th century.

In the end, the railway dealt with 203,041 burials during its 87 years of service, a figure way short of the original estimate.

A London South Western tank engine- the type of model used on the Necropolis Railway during its final years (image: PL Chadwick via Geograph).

The final nail in the coffin (so to speak…) came on the night of 16th April 1941 when the Westminster Bridge Road depot was pounded by a massive air-raid.

Tracks were shattered beyond repair and the funeral carriages (which had originally been designed as coaches for the Royal Family in the early 20th century) were smashed and consumed by flames.

The business limped on, switching to the main platforms at Waterloo, but it soon became clear it was not cost-effective to repair and maintain the service.

The Necropolis Railway carried its final body- that of 73 year old Chelsea Pensioner, Edward Irish in May 1941 and was officially dissolved at the end of the war.

* * *