Van Gogh’s London

Despite being unappreciated during in his own lifetime, Vincent van Gogh is now considered to be one of the most brilliant artists of the 19th century.

Early Life

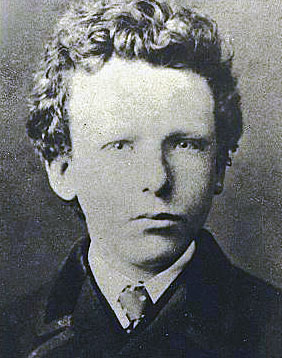

Named after both his grandfather and a brother who had sadly been still-born exactly a year before, Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on the 30th March 1853 in Groot-Zundert; a small village in the southern Netherlands.

As a child, Vincent was noted for his talent in both languages and drawing.

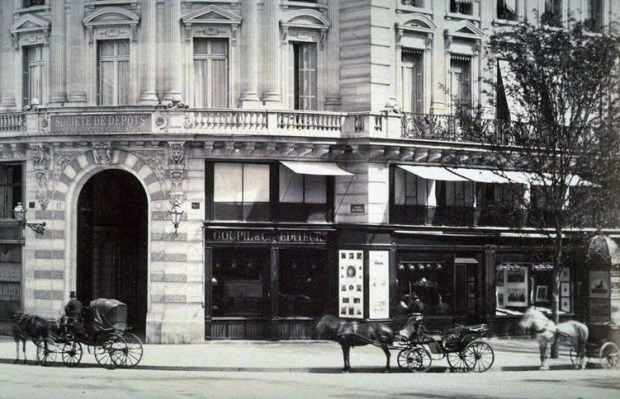

When he reached the age of 16, Vincent’s uncle, Cent helped the teenager secure employment with the art dealer, Goupil and Cie who were based in The Hague and had branches across Europe.

Van Gogh Comes to London

After a four year apprenticeship, the company posted the 20 year old Vincent to their London branch at 17 Southampton Street, Covent Garden in June 1873.

In 1875, whilst Van Gogh was still with the company, the dealership switched premises, moving to nearby Bedford Street, close to the junction with the Strand.

Upon receiving his new role, Vincent was full of energy and optimism and had high hopes for his new career.

Shortly before being sent to London, his mentor, Mr Tersteeg wrote to Vincent’s parents, happily informing them that their son was a popular young man whom both artists and buyers enjoyed working with.

Naturally, the first thing Vincent had to do upon arriving in London was to secure a roof over his head and in his first letter home he mentioned a problem which remains a bugbear for Londoners to his day; “Life here is very expensive…”

The location of Van Gogh’s first digs, where he stayed for two months, is unknown- although we do know that the young Dutchman lodged with two spinsters who kept parrots. No doubt memories of this period would have come to mind when he painted a parrot years later…

Also lodging in the house were three Germans, “Who really love music and play piano and sing, which makes the evenings very pleasant indeed.”

Vincent socialised with the German group but soon found it impossible to keep up due to their lavish spending habits!

During his first few weeks in England, Vincent travelled to Surrey to visit Box Hill, leading him to write, “The countryside here is magnificent.”

Although he could have made the trip by train, Vincent opted to go on foot… a journey which took him six hours.

In another early letter, Vincent also mentions his love of London’s green spaces; “One of the nicest things I’ve seen here is Rotten Row in Hyde Park, which is a long, broad avenue where hundreds of ladies and gentlemen go riding. In every part of the city there are splendid parks with a wealth of flowers, such as I’ve seen nowhere else.”

*

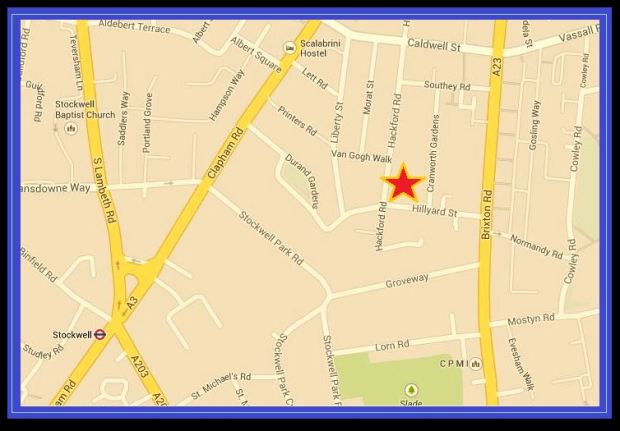

Van Gogh’s second home in the capital- and the building which today provides London’s most noted link with the artist- was at 87 Hackford Road, Stockwell (close to Brixton) where he moved in August 1873.

Thanks to the many letters he wrote to his younger brother, Theo, Vincent van Gogh’s time here is very well documented…and as we will soon see, it tells a sad story which has led to speculation that his time in London eventually came to have a detrimental impact on his mental health; the continuing poor state of which would come to plague the artist in later life.

*

Life in 1870s London

When he first secured lodgings at Hackford Road, Vincent couldn’t have been happier, writing to Theo, “Oh how I’d like to have you here, old chap, to see my new lodgings…I now have a room, as I’ve long been wishing…”

In the same letter, he also mentioned how he “Spent a Saturday rowing on the Thames with two Englishmen. It was glorious.”

“Things are going well for me here, I have a wonderful home and it’s a great pleasure for me to observe London and the English way of life and the English themselves, and I also have nature, art and poetry, and if that isn’t enough, what is?”

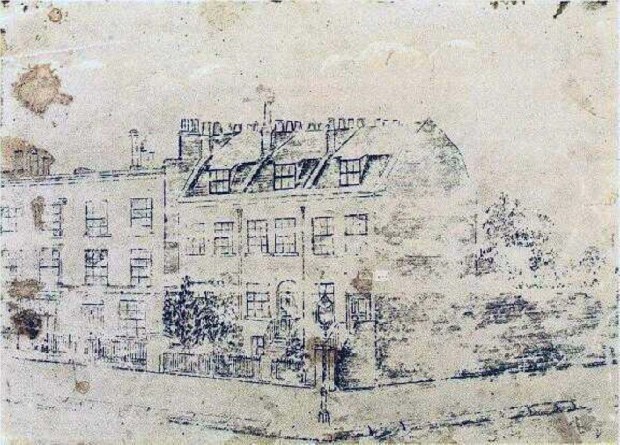

Sketch of 87 Hackford Road by Van Gogh. This drawing was lost for many years before being discovered in a box in an attic belonging to the Great Granddaughter of Ursula Loyer; Van Gogh’s former landlady.

In the early 1870s, Stockwell was still a relatively quiet, genteel suburb and the young Vincent took great pleasure in exploring the surrounding flora and fauna.

“I walk here as much as I can,” he wrote to Theo; “Always continue walking a lot and loving nature, for that’s the real way to learn to understand art better and better. Painters understand nature and love it, and teach us to see.”

*

Donning his specially purchased top hat (“You cannot be in London without one,” he told Theo), Vincent would walk to and from his Covent Garden workplace every day; a journey of some three miles in each direction; “I crossed Westminster Bridge every morning and evening and know what it looks like when the sun’s setting behind Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament.”

On his evening return journey, Vincent would often pause to sketch various views of the Thames- although he was often frustrated in his efforts as he found the perspective tricky to grasp.

During his spare time, the young art-dealer delighted in exploring the city’s galleries and museums and was especially fond of the Royal Academy and Dulwich Gallery. He also visited the British Museum– where he signed the guest book on August 28th 1874.

As well as London’s attractions, Van Gogh also developed a taste for British art and literature; admiring the paintings of Gainsborough and Turner and the novels and poems of George Elliot, Charles Dickens (who had died just three years before Van Gogh’s arrival in England) and John Keats, of whom he wrote “He’s a favourite of the painters here, which is how I came to be reading him.”

He also became an avid reader of The Graphic, Punch and The London Illustrated News; magazines which documented news and topical issues with richly detailed illustrations.

Front page from a copy of the London Illustrated News, printed in August 1873- the month Van Gogh moved to Stockwell. Here, Scottish Black Watch troops are shown training on Dartmoor. Van Gogh was a great admirer of this style of social realism.

The offices of the London Illustrated News were based at 198 the Strand; close to Vincent’s workplace and he would often pop in to pore over the proofs for the latest issue which were available for public view. He even toyed with the idea of becoming a magazine illustrator, but sadly this dream never came to fruition.

Van Gogh was particularly interested in illustrations depicting Victorian Britain’s social ills and he later went onto become an avid collector of the magazines he’d first encountered in London, from which he cut and collected over 1,000 images.

These clippings would be displayed around his studio to inspire and motivate the artist as he worked. “For me,” Van Gogh wrote, “The English draughtsmen are what Dickens is in the sphere of literature. Noble and healthy, and something one always comes back to.”

Scene depicting an Irish family being evicted from their home; one of the many prints in Van Gogh’s collection.

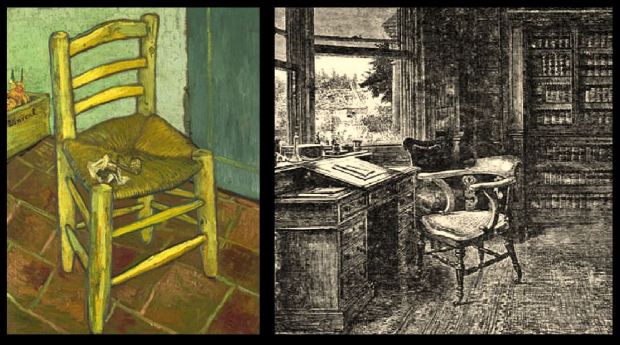

Of the many prints owned by Van Gogh, one in particular, snipped from an 1870 issue of The Graphic, depicted Charles Dickens’ empty seat; a melancholy illustration created shortly after the celebrated author died… and one which perhaps inspired Van Gogh’s own 1888 painting of a chair.

Another print which had an obvious impact on Van Gogh’s work was Gustave Dore’s depiction of convicts in Newgate Prison’s exercise yard, published in 1872’s London: a Pilgrimage.

Van Gogh created his own version of this grim scene in 1890 whilst being held at an asylum in Saint-Remy.

*

The Dream Dwindles

Vincent appeared happy and settled in his new life in London, writing in early 1874 that “I have a rich life here, ‘having nothing, yet possessing all things.’ Sometimes I start to believe that I’m gradually beginning to turn into a true cosmopolitan, meaning not a Dutchman, Englishman or Frenchman, but simply a man. With the world as my mother country…”

Sadly, despite this positive outlook, his mood would soon turn to one of misery.

As the months at Hackford Road passed, Vincent had begun to fall hopelessly in love with his landlady’s 19 year old daughter, Eugenie Loyer.

In the summer of 1874, Vincent finally plucked up the courage to declare his love for Eugenie… but he was told in no uncertain terms that the feeling wasn’t mutual- and that she was already engaged to a previous lodger.

This unrequited love was a huge knockback, sending the once optimistic young man into a spiral of depression and withdrawal.

By this point, Vincent’s younger sister, Anna had joined her brother in London and she too was lodging at Hackford Road. Despite Anna’s attempts to ease the embarrassing situation, the awkwardness between the Van Goghs and the Loyers soon became unbearable.

In August 1874, Vincent and Anna had no choice but to move away from Stockwell, securing new lodgings at nearby 395 Kennington Road with a Mr and Mrs Parker who owned a house known as Ivy Cottage- which has long since vanished.

One Sunday, in April 1875, Van Gogh is known to have travelled to Streatham Common, which he sketched. Tragically, that very same morning, the Parker’s 13 year old daughter, Elizabeth died from pneumonia.

*

Shortly afterwards, Goupils transferred Vincent to Paris where his sadness and isolation continued to plunge further.

Whilst in London, Vincent’s exposure to the plight of the poor; through art, literature and what he himself witnessed on the streets of the metropolis, had led him to develop a deeply committed social conscience.

Now of the opinion that art should be for all, he began to grow jaded with his chosen profession, upset that he was expected to treat art as an expensive commodity.

Consequently, Goupil and Cie April terminated Van Gogh’s contract in April 1876.

Vincent Returns to London

After being sacked, Vincent headed back to England where he hoped to forge a new career in teaching, securing work at a boarding school in Ramsgate where he gave lessons in Bible studies.

Shortly after joining, the school moved to a new location- Holme Court House in the south-west London suburb of Isleworth. Vincent transferred to the new address… but was so poor he had to walk to get there; a journey of over 80 miles which took him three days.

The school in Isleworth offered free bed and board but no salary. Van Gogh stayed until Christmas 1876 but with his prospects limited, he decided to return to the Netherlands, never to see England again.

14 years later, after a poverty-ridden life in which his mental health deteriorated and his art went unnoticed, Vincent van Gogh died aged just 37.

Although he is believed to have shot himself, the gun was never found.

London’s Van Gogh Links Today

A blue plaque dedicated to Van Gogh was not installed at his former Hackford Road home until 1973; exactly 100 years after he moved in.

The house languished in a poor state until March 2012 when it was put up for auction, selling for just over half a million pounds- the buyer is reputed to be an admirer of the great artist.

A video of the interior of 87 Hackford Road, filmed for The Guardian shortly before the sale, can be viewed below.

Just across from the house, a short road formerly known as Isabel Street has been transformed into ‘Van Gogh Walk’.

Unveiled in April 2013 to mark the 160th anniversary of the artist’s birth, Van Gogh Walk is a peaceful tribute which embraces Vincent’s love of nature with sunflower beds and quotes from the letters he wrote in happier times.

A short distance away, opposite Stockwell tube station Van Gogh can be glimpsed on a colourful mural, painted on the entrance to an old, deep-level air-raid shelter.

The young Vincent even appears on the back of the ‘Brixton Pound’; a currency designed to be spent at shops and businesses in the local area!

Where to see Van Gogh’s Paintings in London

The first major exhibition of Vincent van Gogh’s work came to London in 1947 and was unveiled at the Tate Gallery by the Dutch Ambassador.

The Dutch Ambassador opening London’s first major display of Van Gogh’s work, 1947 (image: The Times).

Today, the capital holds a number of important works by Van Gogh which can be viewed below (click the images to enlarge).

If you wish to see the real thing however, please scroll further down for details on where to find each piece.

The Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House:

* Self-portrait; Ear bandaged (1889)

* Peach Blossom in the Crau, (1889)

The National Gallery:

* A Wheatfield with Cypresses (1889)

* Head of a Peasant Woman (1884)

* Long Grass with Butterflies (1890)

* Sunflowers (1888)

* Two Crabs (1889)

* Van Gogh’s Chair (1888)

Tate Britain:

* Thatched Roofs (1884)

* A Corner of the Garden at St Paul’s Hospital at St Remy (1889)

* Farms near Auvers (1890)

* The Oise at Auvers (1890)

From Lost Memorial to Abandoned Tube…

Situated in the very heart of the capital, Nelson’s Column, dedicated to Britain’s most beloved naval hero, is by far one of London’s most famous landmarks.

When it was first unveiled in 1843, the column wasn’t London’s only lofty monument to Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson. If you’d been around at the time and had ventured north towards Kentish Town, you would have discovered Nelson’s Tree…

The tall sycamore was said to have a direct link with Nelson who, as a 12 year old boy in early 1771, travelled from his native Norfolk to spend time with his uncle, William Suckling who lived at Grove Cottage, Kentish Town.

Whilst staying in what was then a very rural north London, Nelson is believed to have tended his uncle’s garden- which included planting the seed that would eventually blossom into the grand tree upon which his name would be bestowed.

Following his stint in Kentish Town, young Horatio headed further south to Sheerness in Kent, where he joined his other uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling, aboard HMS Triumph.

Being sent to sea was something the budding young Nelson had specifically requested he be allowed to do.

His uncle agreed to take him on as a servant, although he was slightly bemused- Horatio was a sickly child, and the captain expressed concern about his nephew being “sent to rough it out at sea.”

Captain Maurice Suckling; the uncle who introduced young Horatio to the Royal Navy (portrait by Thomas Bardwell).

In June 1846, (over forty years after the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar in which Nelson was famously killed), The London Illustrated News reported that the houses surrounding Nelson’s Tree are “to be shortly removed in the formation of a new street; but the Sycamore, we are assured, will be spared.”

Sadly, despite these assurances, no trace of the tree can be seen today (nor can I find details on when it was felled).

The article also stated that, “as a guide to visitors whom curiosity may lead to the locality, we may mention that the Tree stands close to the southern wall of the Castle Tavern.”

Kentish Town’s Castle Tavern was originally built in 1651- the image above represents how it would have appeared during Nelson’s time.

In 1848, the pub was rebuilt on the same spot.

In recent years, the former Castle has had a rather chequered history.

A few years ago, it was turned into a live music joint called the Bullet Club. When this attracted noise complaints, the venue was rebranded The Flowerpot Club… which closed in 2010.

Sadly, this historic building now appears to be in the process of demolition; no doubt a process which will result in the site being replaced with a block of outrageously priced apartments.

*

As mentioned earlier, the 1843 edition of the London Illustrated News mentioned that the now long-lost Nelson Tree could be found towards the southern wall of the Castle Tavern.

Today, this site is covered by another forgotten local relic… ‘Kentish Town South’; one of London Underground’s many abandoned ‘ghost stations.’

Originally planned under the name ‘Castle Road’, Kentish Town South opened in June 1907.

Sandwiched between Kentish Town and Camden Town stations, Kentish Town South suffered low passenger numbers from the off and closed in 1924 after just 17 years.

After being used as an air raid shelter in WWII, Kentish Town South’s street level building was converted into shop units- which are today home to a branch of Cash Converters.

Part of the station is retained as an emergency access and evacuation point and sharp eyed commuters can still spot the hollow, cavernous remains as they whoosh through below.

In 1951, and apparently inspired by a real life (although quickly resolved) incident, Sir John Betjeman penned a short story about the unfortunate ‘Mr Basil Green’, who made the grave mistake of alighting at the ghost station following a mistake by the tube guard…

The full text of this darkly humorous story, which was originally broadcast on the BBC Home Service and takes a gleeful dig at meddling civil servants, can be read below…

* * *

‘South Kentish Town’, by Sir John Betjeman (1951).

This is a story about a very unimportant station on the Underground railway in London.

It was devastatingly unimportant.

I remember it quite well. It was called ‘South Kentish Town‘ and its entrance was on the Kentish Town Road, a busy street full of shops.

Omnibuses and tramcars passed the entrance every minute, but they never stopped. True, there was a notice saying ‘STOP HERE IF REQUIRED‘ outside the station. But no one required, so nothing stopped.

Hardly anyone used the station at all. I should think about three people a day. Every other train on the Underground railway went through without stopping: “Passing South Kentish Town!”

Passengers used Camden Town Station to the south of it, and Kentish Town to the north of it, but South Kentish Town they regarded as an unnecessary interolation, like a comma in the wrong place in a sentence, or an uncalled-for remark in the middle of an interesting story.

When trains stopped at South Kentish Town the passengers were annoyed.

Poor South Kentish Town.

But we need not be very sorry for it.

It had its uses.

It was a rest-home for tired ticket-collectors who were also liftmen: in those days there were no moving stairways as they had not been invented.

“George,” the Station Master at Leicester Square would say, “You’ve been collecting a thousand tickets an hour here for the last six months. You can go and have a rest at South Kentish Town.” And gratefully George went.

Then progress came along, as, alas it so often does: and progress, as you know, means doing away with anything restful and useless.

There was an amalgamation of the Underground railways and progressive officials decided that South Kentish Town should be shut.

So the lifts were wheeled out of their gates and taken away by road in lorries. The great black shafts were boarded over at the top; as was the winding spiral staircase up from the Underground station. This staircase had been built in case the lifts went wrong – all old Underground stations have them.

The whole entrance part of the station was turned into shops. All you noticed as you rolled by in a tramcar down the Kentish Town Road was something that looked like an Underground station, but when you looked again it was two shops; a tobacconist’s and a coal-merchant’s.

Down below they switched off the lights on the platforms and in the passages leading to the lifts, and then they left the station to itself.

The only way you could know, if you were in an Underground train, that there had ever been a South Kentish Town Station, was that the train made a different noise as it rushed through the dark and empty platform. It went quieter with a sort of swoosh instead of a roar and if you looked out of the window you could see the lights of the carriages reflected in the white tiles of the station wall.

Well now comes the terrible story I have to tell.

You must imagine for a moment Mr Basil Green.

He was an income tax official who lived in N.6 which was what he called that part of London where he and Mrs Green had a house.

He worked in Whitehall from where he sent out letters asking for money (with threat of imprisonment if it was not paid).

Some of this money he kept himself, but most of it he gave to politicians to spend on progress.

Of course it was quite all right, Mr Green writing these threatening letters as people felt they ought to have them.

That is democracy.

Every weekday morning of his life Mr Green travelled from Kentish Town to the Strand reading the News Chronicle.

Every weekday evening of his life he travelled back from the Strand to Kentish Town reading the Evening Standard.

He always caught exactly the same train. He always wore exactly the same sort of black clothes and carried an umbrella. He did not smoke and only drank lime-juice or cocoa. He always sent out exactly the same letters to strangers, demanding money with threats.

He had been very pleased when they shut South Kentish Town Station because it shortened his journey home by one stop.

And the nice thing about Mr Basil Green was that he loved Mrs Green his wife and was always pleased to come back to her in their little house, where she had a nice hot meal ready for him.

Mr Basil Green was such a methodical man, always doing the same thing every day that he did not have to look up from his newspaper on the Underground journey. A sort of clock inside his head told him when he had reached the Strand in the morning. The same clock told him he had reached Kentish Town in the evening.

Then one Friday night two extraordinary things happened.

First there was a hitch on the line so that the train stopped in the tunnel exactly beside the deserted and empty platform of South Kentish Town Station.

Second, the man who worked the automatic doors of the Underground carriages pushed a button and opened them. I suppose he wanted to see what was wrong.

Anyhow, Mr Green, his eyes intent on the Evening Standard, got up from his seat.

The clock in his head said ‘First stop after Camden Town, Kentish Town.’

Still reading the Evening Standard he got up and stepped out of the open door on to what he thought was going to be Kentish Town platform, without looking about him.

And before anyone could call Mr Green back, the man at the other end of the train who worked the automatic doors, shut them and the train moved on. Mr Green found himself standing on a totally dark platform, ALONE.

“My hat!” said Mr Green, “wrong station. No lights? Where am I? This must be South Kentish Town. Lordy! I must stop the next train. I’ll be at least three minutes late!”

So there in the darkness he waited.

Presently he heard the rumble of an oncoming train, so he put his newspaper into his pocket, straightened himself up and waved his umbrella up and down in front of the train.

The train whooshed past without taking any notice and disappeared into the tunnel towards Kentish Town with a diminishing roar.

“I know,” thought Mr Green, “my umbrella’s black so the driver could not see it. Next time I’ll wave my Evening Standard. It’s white and he’ll see that.”

The next train came along. He waved the newspaper, but nothing happened.

What was he to do? Six minutes late now. Mrs Green would be getting worried.

So he decided to cross through the dark tunnel to the other platform. “They may be less in a hurry over there”, he thought.

But he tried to stop two trains and still no one would take any notice of him.

“Quite half an hour late now! Oh dear, this is awful. I know – there must be a staircase out of this empty station. I wish I had a torch. I wish I smoked and had a box of matches. As it is I will have to feel my way.”

So carefully he walked along until the light of a passing train showed him an opening off the platform.

In utter darkness he mounted some stairs and, feeling along the shiny tiled walls of the passage at the top of the short flight, came to the spiral staircase of the old emergency exit of South Kentish Town Station.

Up and up he climbed; up and up and round and round for 294 steps.

Then he hit his head with a terrific whack.

He had bumped it against the floor of one of the shops, and through the boards he could hear the roar of traffic on the Kentish Town Road. Oh how he wished he were out of all this darkness and up in the friendly noisy street.

But there seemed to be nobody in the shop above, which was natural as it was the coal-merchant’s and there wasn’t any coal.

He banged at the floorboards with his umbrella with all his might, but he banged in vain, so there was nothing for it but to climb all the way down those 294 steps again.

And when he reached the bottom Mr Green heard the trains roaring through the dark station and he felt hopeless.

He decided next to explore the lift shafts.

Soon he found them, and there at the top, as though from the bottom of a deep, deep well, was a tiny chink of light. It was shining through the floorboards of the tobacconist’s shop.

But how was he to reach it?

I don’t know whether you know what the lift shafts of London’s Underground railways are like. They are enormous – twice as big as this room where I am sitting and round instead of square.

All the way round them are iron ledges jutting out about six inches from the iron walls and each ledge is about two feet above the next. A brave man could swing himself on to one of these and climb up hand over hand, if he were sensible enough not to look down and make himself giddy.

By now Mr Basil Green was desperate. He must get home to dear Mrs Green.

That ray of light in the floorboards away up at the top of the shaft was his chance of attracting attention and getting home. So deliberately and calmly he laid down his evening paper and his umbrella at the entrance to the shaft and swung himself on to the bottom ledge.

And slowly he began to climb.

As he went higher and higher, the rumble of the trains passing through the station hundreds of feet below grew fainter.

He thought he heard once again the friendly noise of traffic up in the Kentish Town Road. Yes, he did hear it, for the shop door was, presumably, open.

He heard it distinctly and there was the light clear enough. He was nearly there, nearly at the top, but not quite. For just as he was about to knock the floorboard with his knuckles while he held desperately on to the iron ledge with his other hand there was a click and the light went out.

Feet above his head trod away from him and a door banged. The noise of the traffic was deadened, and far, far away below him he caught the rumble, now loud and now disappearing, of the distant, heedless trains.

I will not pain you with a description of how Mr Green climbed very slowly down the lift shaft again. You will know how much harder it is to climb down anything than it is to climb up it. All I will tell you is that when he eventually arrived at the bottom, two hours later, he was wet with sweat and he had been sweating as much with fright as with exertion.

And when he did get to the bottom, Mr Green felt for his umbrella and his Evening Standard and crawled slowly to the station where he lay down on the dark empty platform.

The trains rushed through to Kentish Town as he made a pillow for his head from the newspaper and placed his umbrella by his side.

He cried a little with relief that he was at any rate still alive, but mostly with sorrow for thinking of how terribly worried Mrs Green would be. The meal would be cold. She would be thinking he was killed and ringing up the police.

“Oh Violette!” he sobbed, “Violette!” he pronounced her name ‘Veeohlet’ because it was a French name though Mrs Green was English. “Oh Violette! Shall I ever see you again?”

It was now about half past ten at night and the trains were getting fewer and fewer and the empty station seemed emptier and darker so that he almost welcomed the oncoming rumble of those cruel trains which still rushed past. They were at any rate kinder than the dreadful silence in the station when they had gone away and he could imagine huge hairy spiders or reptiles in the dark passages by which he had so vainly tried to make his escape …